Photography via Zeba Talkhani

It’s a warm summer evening in a local bakery in Bloomsbury, and I’m met with the scent of freshly-baked bread and fragrant black tea as I wait for Zeba Talkhani. The author has recently published her memoir, in which she reflects on her experiences of girlhood, feminism, Islam, hair loss, and travelling from Saudi Arabia to India to the UK, all before she turned 27.

Zeba greets me with bags on both arms, carrying a blooming bouquet of yellow sunflowers, with a kind smile spread across her face. She conscientiously apologises for being one minute late and takes her seat.

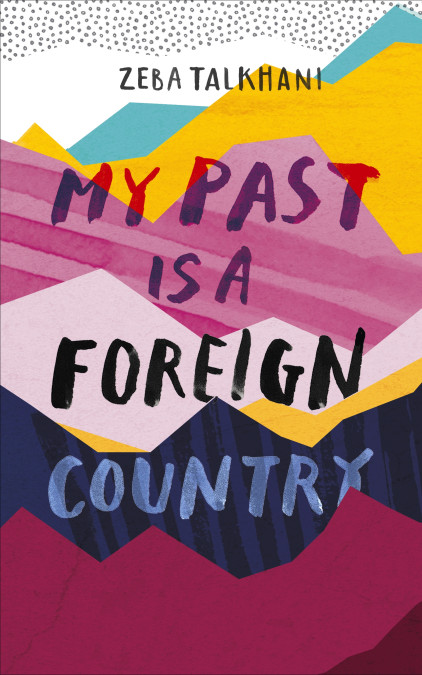

Throughout My Past Is A Foreign Country: A Muslim Feminist Finds Herself, Zeba writes with such eloquence and clarity and discusses topics that feel extremely vulnerable and raw. Even though some might reckon that she’s too young to fill the space of a memoir, she felt a sense of urgency and purpose when writing her book.

“If someone else is going through a similar experience, I want to make sure that the book exists and is there for them”

“As a child, I always waited to be represented in books and I just don’t want the generation after me to have to wait too long,” she says. “It felt like a very pressing thing to get to right away, especially if I had the opportunity to do it.”

She is thankful for her newfound status as a published author and a production editor at Bloomsbury, especially as it sparks the possibility of more representation in a predominantly white industry. “So much about getting a job in publishing seems to be luck, so I’m very grateful for that.” She is constantly checking herself, making it known that she is aware of the weight and influence that her memoir has the potential to carry; it’s as much a necessity for her own mental health and well being as it is for young women of colour readers. “If someone else or someone younger than me is going through a similar experience, I want to make sure that the book exists and is there for them if they need it.”

“One of the reasons why I was able to write the book and feel so good and healed from the experience was because my mother is so supportive”

The act of meditating on past experiences and writing about them in a book sounds cathartic, but for Zeba it wasn’t just her individual anxieties that were put to rest after the publication of her memoir. Her mother has been doubly supportive of her endeavour. “One of the reasons why I was able to write it and feel so good and healed from the experience was because my mother is so supportive and she’s so pleased for me and so proud of me, and that really helped.” Mother-daughter relationships have been presented time and time again in literature, and Zeba’s memoir is no exception. For most of her childhood and adolescence, Zeba’s Mama stayed at home, running the household and tending to her family.

Their physical closeness soon had an effect on her own emotional register: “Very early on I could sense her moods and her emotions, I was so aware of how she was feeling that it had become a part of how I was feeling.” The notion of parental trauma being passed down to children can be extremely formative. Zeba’s unique bond with her mother mapped out much of her adolescent life, including her journey with hair loss, which began when she was 12.

She articulates her journey with a clear sense of conviction and compassion, remembering each doctor’s appointment with sympathy for her younger self. In the book, she remembers having to reconcile with hair loss alongside her mother: “While I was still figuring out ways to come to terms with what was happening, I also found myself consoling Mama whenever she burst into tears at the sight of me studying, walking, reading or talking.”

“A lot of people who have read the book who think that they’re going to be reading about a certain way of life in Saudi have been surprised”

Zeba’s family hail from South India, but she was raised primarily in Saudi Arabia, something that she was keen to write about. “I have found that a lot of people so far who have read the book thinking that they’re going to be reading a certain way of life in Saudi have been surprised. And that’s been good to know because that’s something that we’ve never got to see in our literature.” Whilst many of Zeba’s anecdotal narratives from Saudi are nostalgic and heartfelt, she still grapples in the memoir with the feeling of being an “outsider”.

Her hair loss meant that she had to re-navigate her place within society’s painfully narrow spectrum of beauty, something she felt she could only truly do once she left home to travel for university. For Zeba, travelling to Manipal University in India at 17 and living there alone as a young Muslim girl was already a sign of “exponential” cultural progression for the community. While her parents may have agonised over her decision not to study in Saudi and go to India instead, they still respected her decision and thrust her forward so that she could study journalism.

She writes: “In Manipal, my looks didn’t cause anyone tears. In India I caught people’s attention and I was complimented for my appearance. I was growing into my skin, and the confidence I felt was palpable.” Zeba sighs as she compares this to how people had reacted at home, “The idea of beauty came with having really thick, long black hair.” In certain South Asian communities, long dark hair is a hallmark of feminine beauty – as long as it’s straight. With so much importance being placed on an aspect of beauty that really is skin-deep, it’s inspiring to see another South Asian woman who has liberated herself from old shackles.

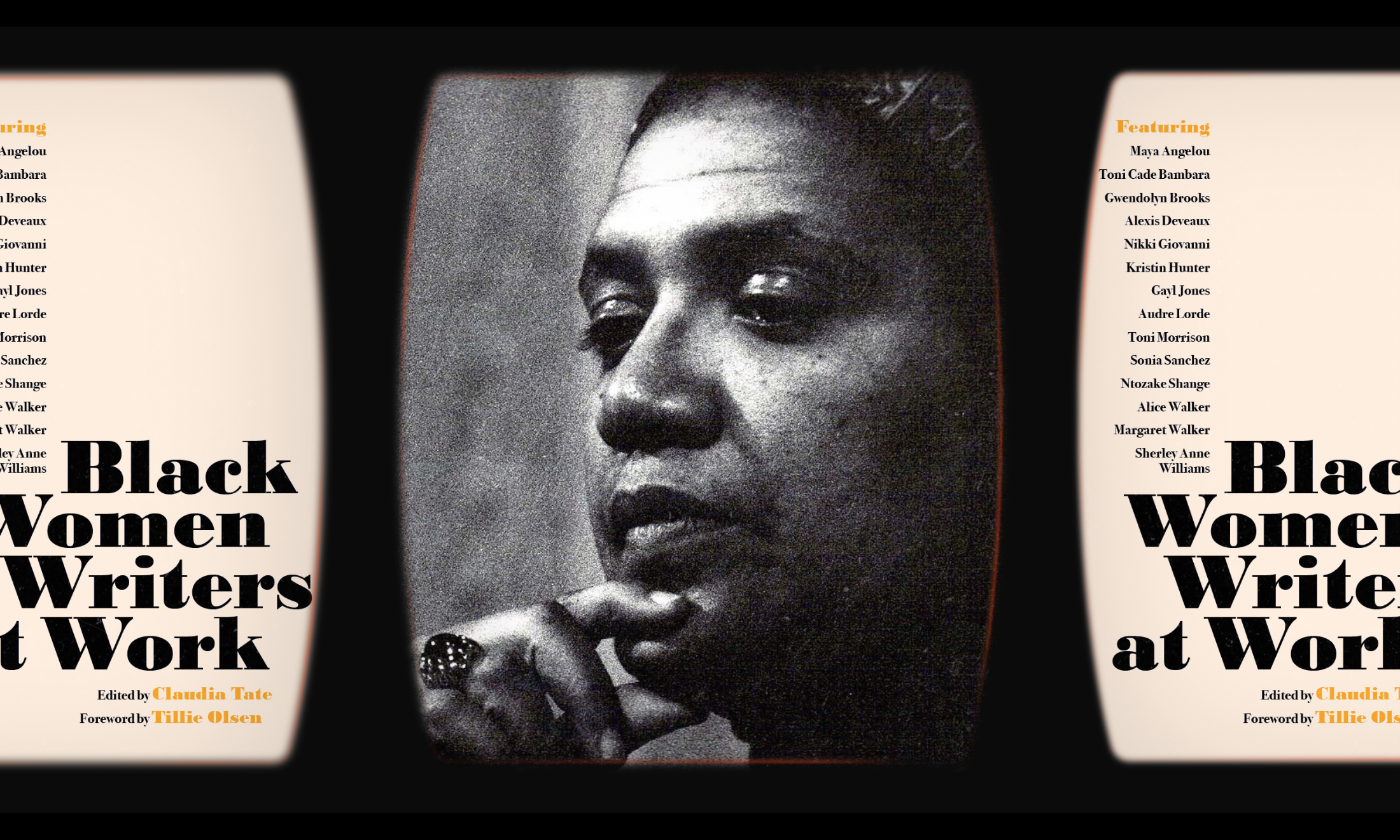

Now, she speaks to me with glowing confidence about her hair loss; it no longer seems like a “burden”. In fact, it’s an intimate personal history that has freed her, which is resonant of her time at university. In Manipal, she was first introduced to writers like Audre Lorde, Simone de Beauvoir and Rachel Cusk, all custodians of feminist discourse. She explains how up until this point, losing one’s hair whilst trying to embody one’s femininity seemed incongruent. But after finding her space within feminism at 20 and consecrating her knowledge of her religion alongside these works, her entry into womanhood “completely changed”.

“I think it completely changed my experience into womanhood and I think it allowed me to enter womanhood as a free woman”

As she says to me now, “I think that it freed me from wanting to feel pretty or knowing that I’m beautiful but not needing the approval of society.” The way that she talks about her own sense of beauty and self-worth is invigorating: “I think it completely changed my experience into womanhood and I think it allowed me to enter womanhood as a free woman.”

Talking about self-worth and womanhood, we immediately stride into a conversation about self-care. Currently, Zeba is sweeping through a whirlwind of press interviews and literary events to promote her memoir. She’ll be talking to author and peer Nadine Aisha Jassat in an upcoming Hub Talks discussion about reclaiming narratives as a Muslim woman of colour.

Looking at your diary and seeing a full written-in schedule can be anxiety-inducing, so I ask Zeba about how she still manages to find time for herself with so many public commitments. “Whenever I see my reflection, all I have to do is smile. If I’m walking anywhere in a mall and then there’s a window reflection and I see my phone, I make a point to smile, to greet myself, to be kind to myself.” With modern life taking its toll, pausing for a breath and practising emotional first aid can seem impossible, so learning to appreciate everything about yourself – the good and the bad – is crucial when it comes to enhancing personal development.

Another aspect of her daily self-care routine that Zeba takes pride in is expanding her knowledge and understanding of her faith. She identifies as a practising Muslim and feminist, using the primary tenets of Islam as guidelines to live by. “I understand that in the mainstream narrative, the idea of being feminist and Muslim is something that doesn’t sit together in people’s imagination. So I feel like that’s something that they’re going to struggle with, which is what was so important to me to write this book and reclaim my faith and my identity.”

“In the mainstream narrative, the idea of being feminist and Muslim is something that doesn’t sit together in people’s imagination, which is why it was so important to me to reclaim my faith and my identity”

Dismantling Eurocentric claims about Islam and trying to ward off antagonists can feel disheartening, especially when some people intentionally try to exclude and erase your narrative from the mainstream, casting your story aside for something more palatable. She broods over the fact that Indian Muslims are frequently made to consign their loyalty to their birth country or their faith as a result of Partition, choosing one over the other. She writes that “being Muslim felt at loggerheads with being an Indian citizen, but things hadn’t always been this way for Indian Muslims”. This sense of tension is something she’s coming to terms with, slowly but surely relieving herself and letting go.

Zeba writes about how her self-study of Islam, feminism and history helped her nurture a seamless relationship between the split parts of her identity, doing away with superstitions that her religion, heritage and feminist identity were not compatible so that she could grow deeper into herself. She writes: “All my old beliefs were cracking under the weight of these revelations. My religion was firm on knowledge being power. And to me, it was power to dream bigger and beyond other people’s hopes for me.”

“Even though people of colour are marginalised in relation to white people, I also recognise that trans people and non-binary people don’t even have the privilege of being recognised”

Knowledge is power, which is why it’s important to identify how reclaiming one’s narrative and combating the erasure of personal histories comes from a place of privilege and choice. “I’m recognised as a woman and my identity is not questioned,” Zeba says, “Even though we [people of colour] are marginalised in relation to white people, I also recognise that trans people and non-binary people don’t even have the privilege of being recognised. So I feel like accepting my womanhood also means accepting any other form of identity or the choice for others to choose the identity that they want because I’m able to choose the identity that I want.”

Zeba’s memoir is carefully constructed, as though she’s traced each sentence a million times before giving in the final draft, and it shows through her writing. She acknowledges how authors before her have breathed into her literary conscience, citing Outline by Rachel Cusk, Comfort Zones (an anthology published by Jigsaw), Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls: A Memoir by T Kira Madden, Saltwater by Jessica Andrews and Exposure by Olivia Sudjic as some of her favourite texts.

Our interview ends and I nestle Zeba with a hug. She’s excited for what the future holds for successive generations, saying that she can’t wait to support our journeys and helps us cradle our ambitions. I leave the bakery beaming, hoping that I can mirror the same grace and elegance that she has inspired in herself.

Zeba Talkhani’s My Past Is A Foreign Country: A Muslim Feminist Finds Herself is out now on Hodder & Stoughton