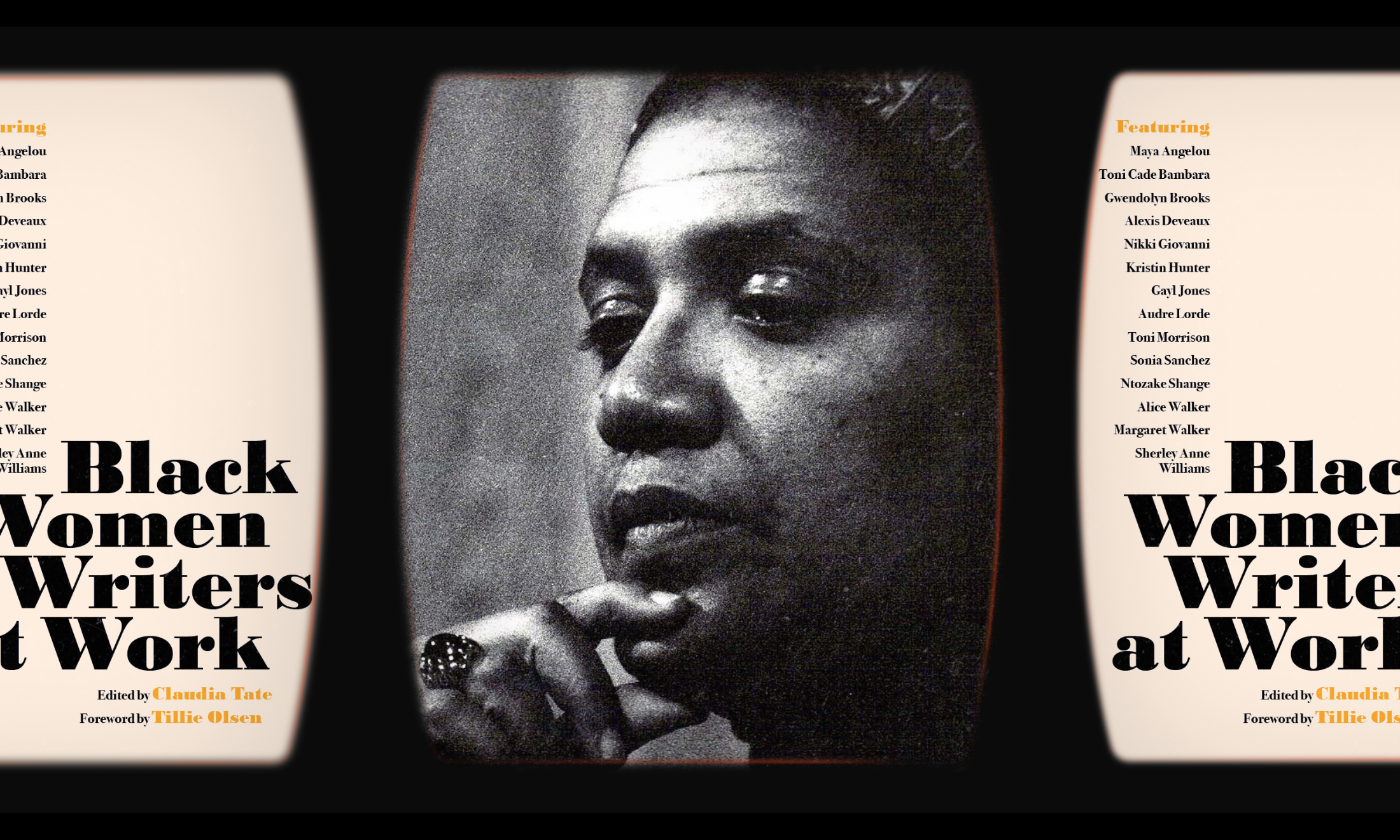

Monica Macias/Duckworth Books

Growing up as a Black girl from Pyongyang

In an extract from her memoir, Monica Macias reckons with the realities of moving from West Africa to North Korea under the guardianship of Kim Il-Sung.

Monica Macias

06 Mar 2023

Content warning: disordered eating, racism, death

The story I want to share with you in this book is an unusual one. Why? It is uncommon because I was born the fourth child of Francisco Macias, the first legitimate president of independent Equatorial Guinea, a small country and former Spanish colony in West Africa, but I was raised by Kim Il Sung, the former president of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), otherwise known as North Korea. Now, you might wonder why my father would choose to send us – for it was not only me but two of my siblings too – to Pyongyang, North Korea. Well, to understand that I need to give you a bit of context; the full picture will emerge as you read the book.

This is where arguably the two most important processes in our modern history, which shook and shaped so many millions of lives, take centre stage: colonisation and decolonisation. Colonisation was characterised by the ruthless exploitation of the colonised by colonial powers. People from those colonised territories were considered subhuman, inferior to white people, with no rights whatsoever, including the right to education.

“I was seven years old, and I hadn’t seen my father since arriving in North Korea”

As a consequence, in the aftermath of decolonisation there were no proper educational institutions in Equatorial Guinea. This prompted Macias’s decision to send young Guineans, including us, his own children, to study abroad. And relations between Equatorial Guinea and its former coloniser, Spain, were so difficult that Kim Il Sung’s offer of fraternal assistance was welcome. Moreover, deeply disillusioned by their relations with former colonial powers, many emerging independent African nations were open to offers of solidarity and support from Russia, China, Cuba and North Korea.

Not long after I moved to North Korea to study, my father was put on trial in Equatorial Guinea on 24 September 1979, accused of perpetrating atrocities during his time in office, along with other allegations. During the trial, he requested a thorough investigation. However, his voice was not heard and his version of events was not taken seriously. He was found guilty on 29 September 1979 and, with no right of appeal, executed by firing squad on the same day. I was seven years old, and I hadn’t seen my father since arriving in North Korea. At the time, what was happening back in Guinea was mysterious to me, and it would remain so for many years to come.

***

I had a burning sense of embarrassment about being different. I was not only black, but unusually large and tall for my age. Some of the children at school would touch my curly African hair and call me yang ajumŏni (‘sheep wife’) after a popular cartoon character. I would blush to my roots.

I had not heard from my father or Teo since we left Malabo. According to my sister – though I do not remember the moment – after a few months, my mother suddenly announced that she had to return to Equatorial Guinea. We were to be sent to the Mangyŏngdae Revolutionary Boarding School in the eponymous district of Pyongyang, some thirty minutes southwest by car of the city centre.

The school had been established after the colonial period to educate the children of Korean martyrs in the struggle against Japanese rule before the Second World War. In the late 1980s, the school began accepting the children of party members. The school then took a special step to accommodate my sister and me. On the order of Kim Il Sung, what was originally a boys’ school became mixed gender. Ten additional girls were brought in to create a form for me, and about the same number for my sister, who was fourteen.

As our black car drew up in front of the main school building on that hot July day, an old man stood waiting for us in military dress. He was wearing an impeccably pressed khaki uniform, shiny black shoes and a khaki hat. He saluted and shook hands with each of us in turn. An excited Fran, now eleven years old, mimicked him behind his back.

This man, O Chae Won, was the school director. He led us to his office, a large room with a balcony leading off it. We sat down on a sofa near his large, neat desk and Director O began to address my sister, as the eldest of the three of us. By this time, we spoke good Korean.

‘I am glad to tell you that you have the privilege of studying at the Mangyŏngdae Revolutionary Boarding School,’ he said.

While Director O and my sister talked, Fran got up and walked out onto the balcony. I followed him. We gazed out over the sprawling grounds of the school, which was surrounded by a wooded park. From the balcony you could see five large buildings arranged around the school’s playing fields, housing a clinic, library, theatre/cinema, gym, canteen, laboratory and dormitory. Outside the main building loomed a large statue of Kim Il Sung.

Suddenly a voice barked at us from inside. ‘Fran, hold your sister’s hand in case she tries to climb the balcony railing.’ It was Director O, and it sounded like an order.

‘Yes, sir!’ said Fran, as if he too were a soldier. He took my hand.

We were taken to be introduced to our new classmates. They came from all over the country, mostly from lower-ranked social backgrounds. All of my new classmates were fatherless. In later years I realised that they had been deliberately selected on this basis.

Another fact about my classmates became immediately apparent: although they had been chosen to make up a cohort for me, all of them were two years older. As my age did not match the school year, my study schedule was slightly different. I joined them for their second-year primary school classes in the morning, and while they played in the afternoon, I attended first-year classes on my own to catch up.

“I was used to speaking on a whim, when the thought occurred to me, but this was frowned upon”

Years later, just before I left the school, I learned that my classmates had been chosen in order to approximate my height; naturally that meant I would be the youngster of the class for the remainder of my time in the North Korean education system.

At the time, this did not surprise me in the slightest, but it interests many Westerners when I tell them. I guess it is a cultural thing because it does not surprise South Koreans either.

Another problem – and a worse one – came with adapting to school discipline. Our class – or platoon, in the military terminology favoured by the school – had a platoon leader, a sotaejang, a pretty and surprisingly even-handed young woman whose job was to keep us in line according to the school’s strict standards of discipline. I admired my new classmates for their energy and positive outlook, but they lacked spontaneity. They did nothing without asking permission. Everything, even going to the toilet, required permission. I was used to speaking on a whim, when the thought occurred to me, but this was frowned upon. I complained about that in the early days at school. ‘Remember, you are a soldier!’ my teacher responded. I could not understand how I could be a soldier in a foreign country.

I also found it difficult to relate to my new classmates because I could not read them well. When they spoke, they often seemed rigid and expressionless (until you got to know them). This is a trait that East Asians now remark upon in me. ‘I feel like I’m speaking to an Asian,’ a Japanese woman I met in the Netherlands once said to me as we became acquainted. But at the time, motherless, fatherless and wrenched from my home and the creature comforts of my early life in Korea, I found the lack of warmth and openness shattering, and I struggled to adapt.

Every night, I spent hours crying in bed. At six a.m. the morning routine came around like a wheel to crush me. The reveille would sound. We had to run around the playing fields before breakfast. Classes began at eight a.m.

After classes finished at two p.m., we went for lunch, along with Herve and Montan, the sons of Mathieu Kerekou, president of Benin, our friends and the only other black students in the school. We Guinean and Beninese children were served in a different room, with food cooked by a different chef as a courtesy to us. By this point I could not stand Korean food, and in particular kimchi and tofu. I had always been picky with food, even at home in Equatorial Guinea.

And I yearned for my mother, who had not returned. I did not know why.

My anguish drove me to refuse all food. For a month, nothing passed my lips but water. My weight plummeted, raising fears that I might die. I was taken to Ponghwa hospital, where I was put on a glucose drip that kept me alive. Even there, my nights were spent crying: ‘I want my mum.’

A month later, when I had recovered, I went back to school. My classmates were relieved and happy to see me back. Some of the barriers between us dissolved. Special food was couriered from a hotel in central Pyongyang for me to eat. This made my day-to-day life easier, but no one could replace my mother. There was no news of her. I just had to accept that she was gone.

“I wanted desperately to blend in with my classmates, but their unspoken message seemed to be: ‘You are not Korean, you are not like us.'”

From this point onwards, my attitude changed, hardening from my natural ebullience into an overt rebellion against authority and hierarchy. I did not understand why I had to live in that boarding school under such strict discipline at only eight years old. I was one of three girls in my class who vied for dominance over the others. I spoke disrespectfully to others and showed little regard for Korean social ranking according to age, for which one of my sister’s classmates took me to task.

‘What’s wrong with you? You know you cannot speak to me like that. I am older than you! You should respect those older than you,’ she said.

I simply ignored her.

My feisty attitude masked an acute sense of social rejection. I wanted desperately to blend in with my classmates, but their unspoken message seemed to be: ‘You are not Korean, you are not like us.’ Biology and history classes seemed geared to accentuate my difference. In history, we studied ancient Korea, from the Three Kingdoms era to the Koryŏ dynasty, the Chosŏn era to Japanese occupation. For a moment, my interest in my adoptive country would be piqued, until I would suddenly notice one of my classmates giving me a sly look that said, unmistakably: ‘This history has nothing to do with you.’ It was true. While for them this was the story of their grandparents and great-grandparents, for me it was just a class.

Biology class also triggered personal questions about my differences. Why am I brown when my friends are yellow? I wanted to be like them, with yellow skin, straight black hair and almond eyes. I hated my brown skin, big eyes and curly hair. I used to tell myself, ‘I am Korean, I am Korean,’ while combing my hair to try to force it straight, but it never worked.

However, as an adult my sister showed me a letter that my father wrote to accompany us when we were sent to Pyongyang.

My dear children,

I send you to Pyongyang in the charge of my friend Kim Il Sung whom I respect as a brother, to study. He will take care of you and put you into whichever school he considers is right for your education. Do not ever forget who you are. You are African. You should go back to Guinea to build this country after your studies. Our country needs you. Never forget what Spanish colonists did to our country. From your father who loves you,

Francisco Macias

In my mum’s absence, Kim Il Sung was now my guardian, and I was effectively an orphan. I had lost my parents, my home, and the sense of security those things provided. I had to become prematurely independent and to grow up, fast. My sister, friends and my tutors filled the void left by my mother. My life became a structured one, dominated by discipline, in which loneliness was my bosom companion.

Black Girl from Pyongyang is released March 2023 and available here via Duckworth Books.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.