Inquilaab Zindabaad: Why Sikhs all over the world are protesting with farmers in India

Farmer protests in India are a historic show of solidarity against neoliberalism and Hindu nationalism – and the Sikh faith is at the heart of it.

Mandeep Sidhu

11 Dec 2020

Image via Twitter/@Hark1Karan

Trigger warning: This article contains mentions of suicide

At a time when governments should be focused on addressing the Covid-19 pandemic, India’s ruling party is targeting farmers.

In September, ruling right-wing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) issued emergency executive orders to pass a set of contentious farming bills which will impact 40% of the country’s workforce. These farm reforms deregulate the processes by which farmers sell their produce through bypassing mandis (state markets), risking farmers’ crops being devalued as they’re left at the mercy of corporate buyers’ demands. Whilst mandis have their own problems, the bills are set to leave farmers unable to collectively hold corporate monopolies to account.

The bills have been widely opposed by agricultural workers, unions, and opposition parties, culminating in a 300,000-strong mass march to Delhi from northern agriculture-heavy states like Punjab where 70% of the population is directly or indirectly involved with agriculture. Protestors are occupying roads on the borders of Delhi by setting up camps with food supplies to last months.

Solidarity protests, strikes, and shutdowns have also been held: 26 November saw an estimated 250 million Indian workers taking part in a nationwide strike – which is being hailed as the largest organised strike in history, with one fifth of the population turning out to demonstrate. Protestors have mobilised for a wide variety of reasons, but their peaceful protests have been met with lathi charges (batons), water cannons, tear gas, and violent police brutality.

In Punjabi diasporas, a number of politicians, singers, poets, and public figures have spoken up in support of protesting farmers, while in India, a huge number of Punjabi public figures have returned and rejected state-awarded accolades. Across the world, from California and London, to Vancouver and Melbourne Sikh Punjabi communities gathered in Covid-19 safe car rallies to protest in solidarity with Punjabi farmers.

Where do the Sikh diaspora protests fit into this?

Punjab is a Sikh-majority state from which many diaspora Sikhs like myself trace their religious, cultural, and agricultural roots to. The region was violently partitioned by British colonial rule in 1947 and further reorganised into separate territories in 1966, both triggering disputes over access to water. Importantly, Punjab was the epicentre of the Green Revolution from the 1960s which catalysed the increased commodification of agriculture: shifting away from indigenous, diverse crops and overhauling centuries-held knowledge systems about food and land in favour of monocultures and chemicalisation of the land. The latter has been correlated to cancer rates in agricultural states like Punjab and increased crop failure from pest-resistant incidences.

Pressure to invest in new agricultural technologies to prevent crop failure pushes farmers into debt, with a 2018 government report revealing that over half of all agricultural households in India are in arrears. In Punjab, debt levels are two and a half times greater than the national average; overwhelming financial burdens have been attributed to rising suicide rates in agricultural areas of Punjab, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and elsewhere since the 1990s.

Sikhi is actively shaping and strengthening the current farmer protests. Iconography of the Sikh faith (orange colours, the Khanda symbol) has a heavy presence both at Indian and diaspora demonstrations, with a mobile Gurdwara (Sikh socio-spiritual home) set up at one protest site to offer spiritual strength to protestors. Despite this, existing analysis overlooks the role of the Sikh dharam (faith) in shaping and supporting protests both in India and abroad.

Since the formation of the modern state in 1947, Sikhs have been targeted as a minority faith community in India. 1984 saw the state-sanctioned raid on Harmandir Sahib, the spiritual and temporal home of the Sikhs. Since then, thousands of Sikhs have gone missing in “fake encounters” with the Punjab and Indian state, with Scottish-Sikh activist Jagtar Singh Johal currently having been detained for over three years.

The Indian state’s treatment of Sikhs has provoked and justified demands for Sikh autonomy and sovereignty, largely communicated through the call for Khalistan, “land of the Khalsa”, the Sikh order formed in 1699. BJP and government-supporting “godi media” in India have used these historical struggles to label protestors in India and the diaspora as terrorists, in failed attempts to break down the solidarity between workers and those of differing castes and religions unified in the rallying cry “Kisaan Majdoor Ekta Zindabaad,” meaning “Long live farmer/worker unity”.

The complex material conditions agricultural workers experience and their reasons for protesting mustn’t be homogenised. From women agricultural workers not being formally classified as farmers – which excludes many from government initiatives – to disparities between land-owning farmers and marginalised landless workers who are often from ‘lower’ castes and indigenous Adivasi communities, intersectional dynamics of gender, caste, religion, and other hierarchies must be taken into account.

Resistance to the farming bills should be understood, both in India and diasporas, in their wider socio-political context of the BJP’s agenda of marginalising minorities deemed an existential threat to a mythologised notion of India as a purely Hindu nation, neoliberalism, and broader historical socio-political relations between minorities and the nation-state.

Protestors suspect the farm laws are rigged to benefit corporate backers of BJP Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 2014 winning election campaign, Ambani and Adani, whose wealth has doubled since Modi’s victory. Modi’s regime, which has seen anti-Muslim citizenship laws passed and lynchings against minorities increase, is heavily entangled with corporate interests.

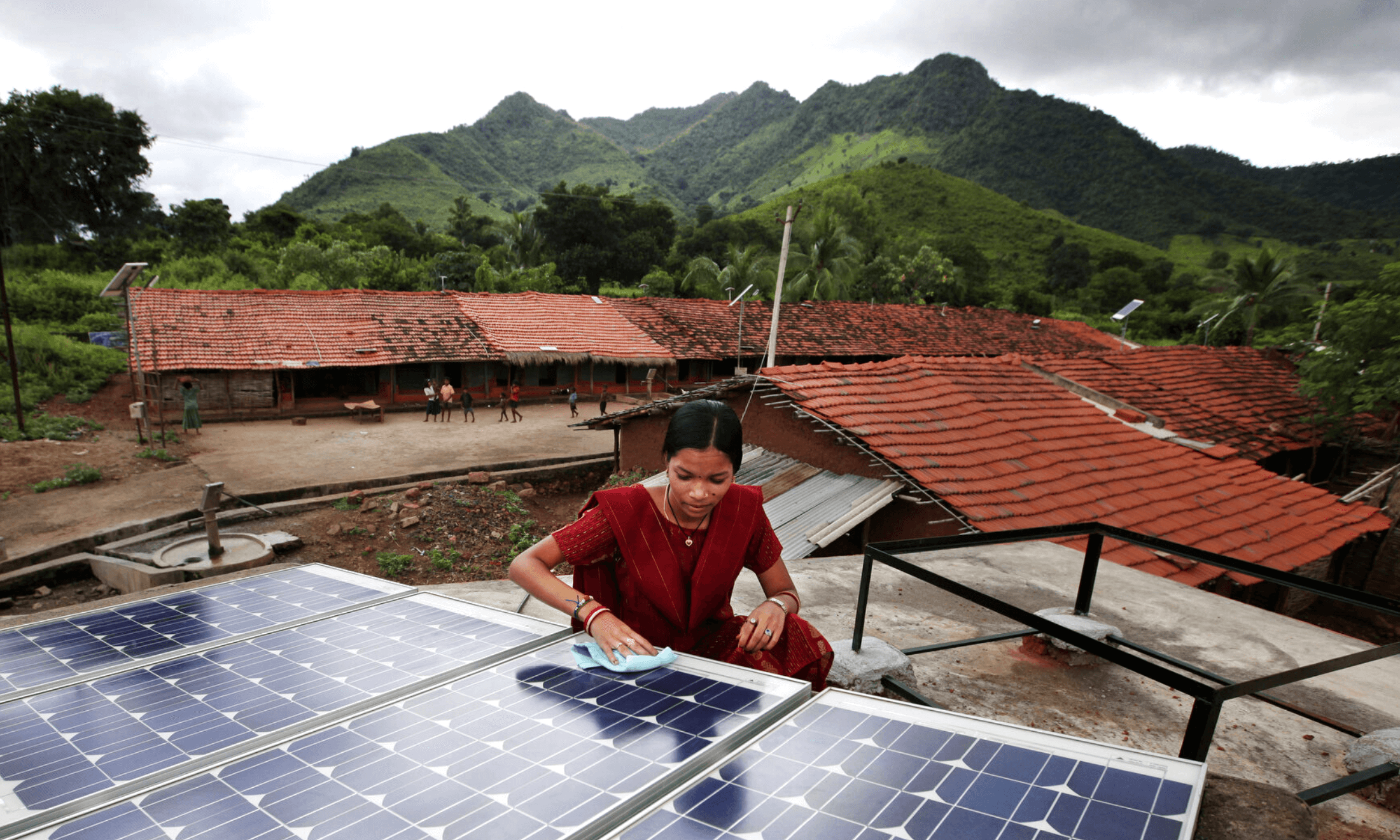

Protestors are showing no signs of backing down. Diaspora protests continue to take place most weekends, and UK Sikh student societies are raising funds for charities Kheti Virasat Mission and Sahaita who are supporting the protests, agricultural livelihoods, and sustainable agricultural practices in Punjab. In the wake of “godi media”, it is important to amplify protestors’ resistances by spreading solidarity and awareness online, and countering Boris Johnson’s ignorance in confusing the protests with Pakistan-India land disputes by writing to your MP, asking them to condemn the violence protestors are facing in India.

ਇਨਕਲਾਬ ਜ਼ਿੰਦਾਬਾਦ

Inquilaab Zindabaad

Long live the revolution.

Mandeep Sidhu is a member of Sikh Socialists

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?