Cross-border queers: how we’re digging up lost histories of LGBTQI+ South Asian migrants in Britain

An academic project is unearthing the UK's rich and relatively unexplored history of queer South Asian communities in the 20th century.

Churnjeet Mahn and Rohit K Dasgupta

24 Feb 2021

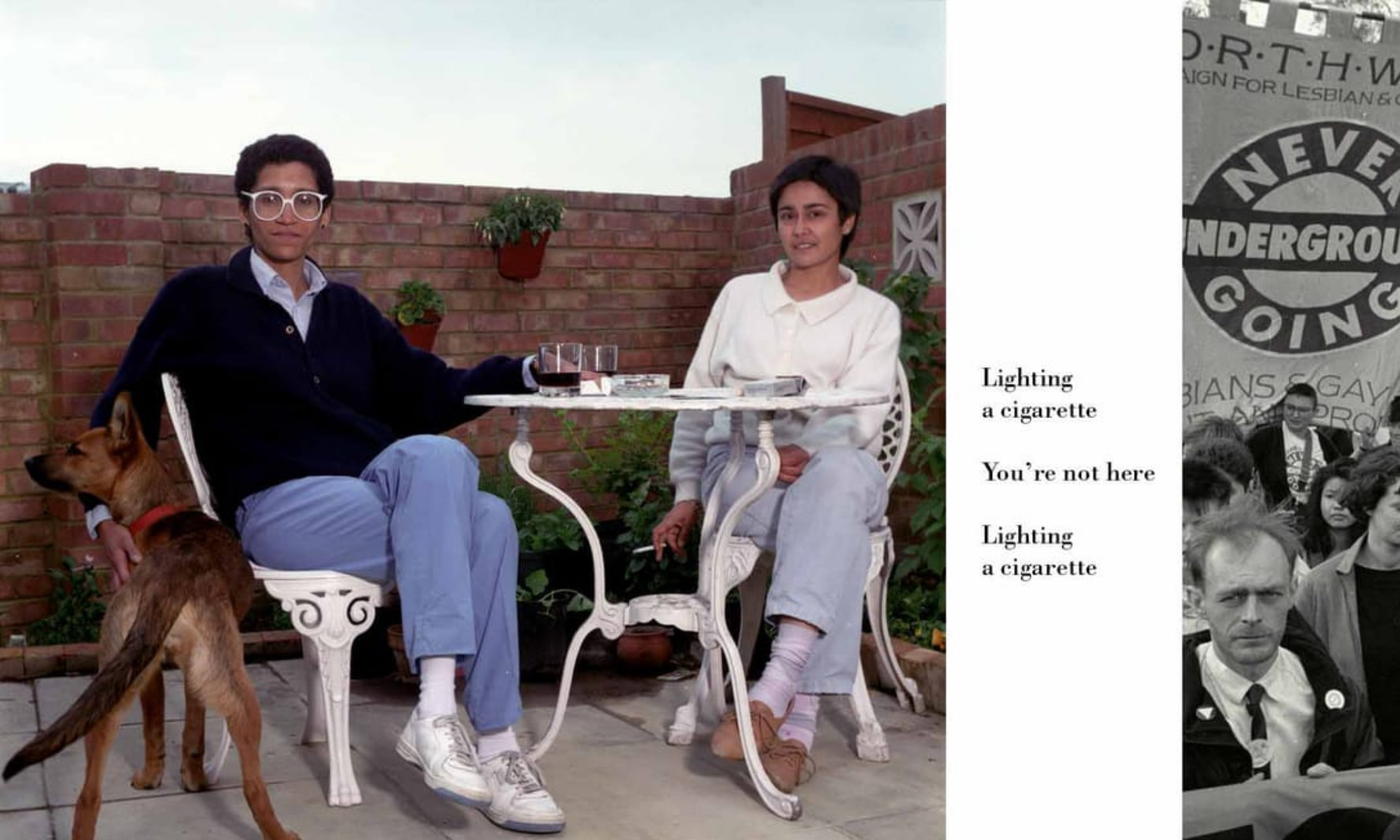

Sunil Gupta

Photography: “Pretended” Family Relationships, Untitled #07. Image courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, Stephen Bulger Gallery and Vadehra Art Gallery. © Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020.

South Asian migration to the UK is a topic that has been pored over for decades. But there’s a key part of the tale missing: the experiences of queer South Asian migrants who came to the UK in the 20th century. As two academics, our research project – titled “Cross Border Queers: the story of South Asian Migrants in the UK” – aims to fill in some of those gaps and challenge both the whitewashing of British queer history and the ‘heterowashing’ of migrant history.

The stories we’re telling aren’t new, they’re just ones that have found themselves on the fringes. They are uncomfortable truths for gatekeepers who’ve been able to shape more homogenous and mainstream versions of ‘their’ communities. But for us, they’re a vibrant and vital excavation of lives that deserve to be lived in the light.

Nascent organising

The late 1960s and early 1970s mark the beginning of an organised LGBTQI+ civil rights movement in the UK in the form of organisations such as the Gay Liberation Front. At the same time there were larger waves of post-war migration to the UK, with people of South Asian descent arriving from India, Pakistan, Kenya, Uganda, Malaysia and Singapore. So it’s no accident that when we look into the political organising of a generation that came of age in the 1980s, we see connections between radical queers and anti-racist activism.

For example, the Glasgow Women’s Library archive houses a collection from the Lesbians and Policing Project (LESPOP London) which has posters from 1985, offering practical advice about how to respond to police raids. What’s remarkable is the poster was translated and printed in languages such as Punjabi, suggesting that these posters were circulated in South Asian communities. At a time when being a lesbian could make you be seen as a ‘bad parent’, or a danger to children, lesbian resistance could connect with the experience of migrants who were also targeted by a state hostile to their presence.

The 1980s and 1990s show us the beginning of queer organising in Britain’s South Asian communities. The foundation of Shakti, a South Asian lesbian and gay group, in 1988 was a key moment. Some of the founding members of the organisation revolutionised the lives of the younger generation. Pratibha Parmar’s films brought queer South Asian women to the silver screen for millions of young people. DJ Ritu, who co-founded Club Kali in London, created a music venue where the fusion of musical styles could offer new vocabulary of experience to young queer people tackling social issues in their daily lives.

“At a time when being a lesbian could make you be seen as a ‘bad parent’, lesbian resistance could connect with the experience of migrants who were also targeted by a state hostile to their presence. ”

The period also represented a moment of transnational organising across the South Asian diaspora. Trikone, founded in 1986, was an organisation for queer desis that spanned North America, Europe and India. Another important facet was the emergence of queer digital spaces on the internet such as the Khush mailing list in 1993, a virtual support network for “gay, lesbian, bisexual South Asians and their friends”. Khush was joined by Gay Bombay in 1998, a website which helped connect a transnational South Asian queer community through the internet. Digital spaces allowed diverse queer communities of solidarity to form across the world.

But the radical potential of these decades was interrupted by the devastating legacy of 9/11 which brought a heightened sensitivity to sectarian politics within South Asian communities, itself a legacy of the British colonial project. It became more meaningful for some queer South Asian Muslims to find solidarity with other queer Muslim diasporas in the UK. The experience of Islamophobia and homophobia became a distinct issue in public discourse (from sex education in schools, to stereotypes about Islamic cultural values) that was used to target, and single out, Britain’s Muslim communities, subjecting queer Muslims to even more, intersecting, stigma.

Cultural activism

A large part of this project has also been focusing on cultural activism – to see how activists have used creative practice to advance social change.

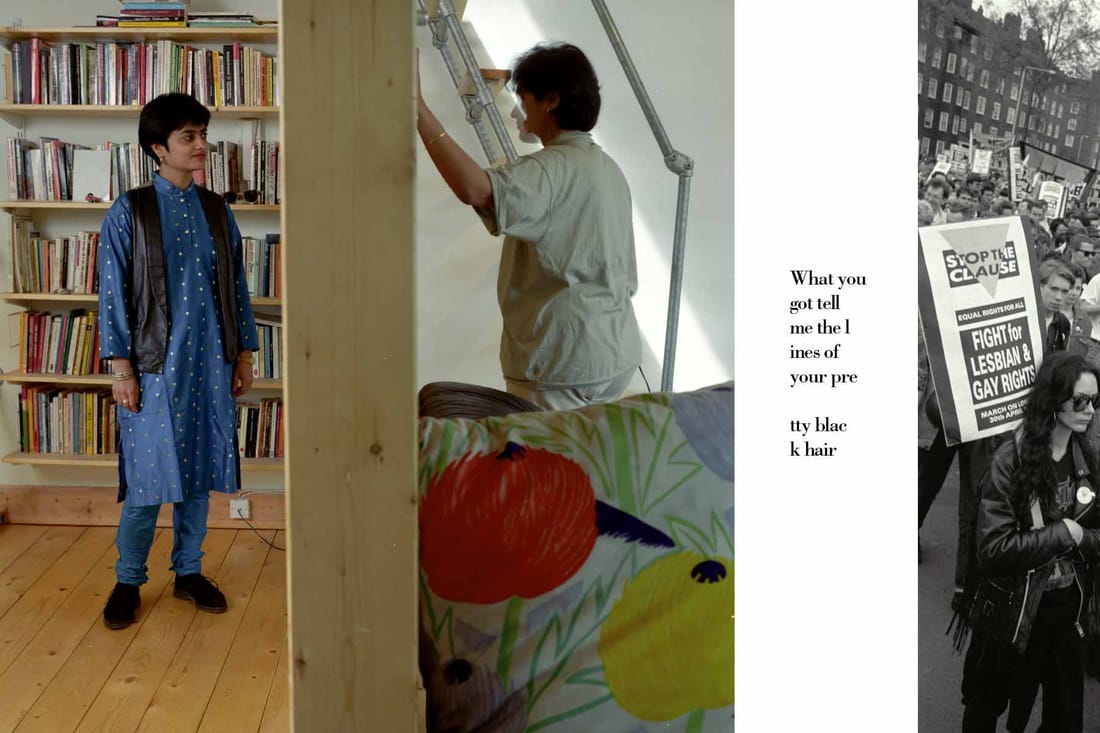

Artist Sunil Gupta, an interviewee for the project, moved to London in the 1980s, migrating from India via Canada where his parents had originally settled. Sunil became involved in anti-racist and LGBTQI+ struggles and has used photography to document key moments of queer history in the UK. In Pretended Family Relationships (1988) he responds to Section 28, which forbade representation of homosexual relationships as “pretended family relationships” – aka preventing queer families from being normalised.

In another series, From Here to Eternity (1999), Sunil depicts being diagnosed HIV positive as a form of therapy. His fictional narrative Sun City (2011) tells the story of a gay South Asian immigrant against a backdrop of promiscuity, racism and HIV/AIDS. Sunil’s work has been particularly helpful for us to think about queer spaces in the UK and the various ways through which South Asian spaces are reconstructed through queer lives and desires – his practice offers uniquely alternative ways of thinking about colonial histories and queer postcolonial futures.

Image courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, Stephen Bulger Gallery and Vadehra Art Gallery. © Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020.

We are also looking at the work of South Asian filmmakers such as Ian Iqbal Rashid, Pratibha Parmar and Faizan Fiaz, all of whom will be interviewed over the course of this project. Rashid’s 1997 film, Surviving Sabu, explores the difficult relationship between a conservative father and his gay son. The oedipal narrative of the father-son relationship as depicted in Rashid’s film lies at the interstices of colonial legacies in a postcolonial Britain.

Pratibha Parmar, who was born in Nairobi and moved to the UK in the 1960s, has similarly used her background in feminist and anti-racist organising to explore the everyday realties of South Asian queer women. Her documentary Khush (1991) and her debut feature Nina’s Heavenly Delights (2006) captures the experience of being South Asian and queer in Britain. Khush – an Urdu word meaning ‘happy’ – traces the formation of homophobia within the Indian diaspora to colonialism.

Going forward

South Asian history in the UK is a legacy of colonial exploitation. The people we’ve spoken to as part of our project have given us snapshots of queer South Asian life in the UK over five decades. We’ve been following the threads that connect these disparate voices over time, and across continents, to ask who Britain’s desi queers are and why their history may be challenging for communities in the present who want to imagine different pasts. So much South Asian migrant history and heritage in Britain focuses on a classed story, a narrative of working class migrants bringing their ‘traditional’ food and their ‘culture’ to British shores.

But these ‘traditional’ cultures quickly became a way of creating static or homogeneous representations of South Asians, which was – and still sometimes is – viewed as an identity irreconcilable with being queer. In many white British retellings, South Asian cultures were too ‘backward’ to understand queer rights, another version of white saviourism that entirely neglected the rich histories of queer life in South Asia seen in ancient temples, in art, in literature, and social groups, like kothis and hijras.

“It’s time to create a desi queer heritage in the UK so we stop atomising young people, and stop them from thinking this history does not exist”

What does the story of queer liberation look like when – instead of routing it through key moments like Stonewall in the US, or the miner’s strikes in the 1980s – we add accounts of the queers of colour who battled racism and homophobia on the streets of Britain? Queers of colour who came from cultures with rich histories of sexual difference, but were told and taught that they were homophobic, that they were the problem?

Like many queer oral history projects, we hear the same stories again and again across the generations. The fear of coming out to family, and the repercussions on broader community relations. The experience of racism in white-dominated queer spaces, which, when highlight, sees you regarded as just another child of a migrant with a chip on your shoulder. Too many times, these experiences have led to silence or isolation. It’s time to create a desi queer heritage in the UK so we stop atomising young people, and stop them from thinking this history does not exist. We’ve always been here.

Cross-Border Queers is funded by a British Academy Grant. A co-authored monograph from this project will be forthcoming in 2023.