Boohoo’s attempts to appear ethical are empty and damaging – we must keep calling them out

The fast fashion brand’s disdain for workers and protesters is clear – as I felt firsthand.

Zainab Mahmood

08 Mar 2023

Georgia Baker-Smith

Sometimes when I feel the terms ‘unethical’ and ‘exploitative’ don’t do the harms of the fashion industry justice, I call it violent. That violence briefly became my reality as I and five other protesters were physically removed from a Boohoo panel discussion in February on ethical sourcing for challenging their so-called ethics.

Boohoo Group, which owns fast fashion brands Boohoo, Pretty Little Thing and Nasty Gal, made £882m in revenue in six months in 2022. Boohoo operates on fast production and trend cycles, uploading hundreds of new items to its website every week and offering discounts of up to 90%. These are just a handful of the reasons why Venetia La Manna, a friend and fair fashion campaigner, decided that the Boohoo panel on 14 February at Source Fashion, a new sustainable sourcing show, would be the perfect opportunity to call the brand out.

“It’s hard not to reel at the audacity of talking about collaboration without including garment or warehouse workers”

The panel was titled ‘A fashion focus: Ethical clothing starts with industry collaboration’. But all panellists were Boohoo employees and thus we felt that neither the brand’s “industry collaboration” nor ethics could be truly challenged. As a representative for Boohoo Group later told me via email, “the discussion was talking about how [they] collaborate with other government, other retailers, NGOs and others in order to find solutions to [their] shared challenges.” Further, the event organiser, Source Fashion “always intended for this to be a single company talking around their work in this area”. Even so, it’s hard not to reel at the audacity of talking about collaboration without including garment or warehouse workers.

Our aims were both to de-platform the brand and expose their controversial practices, including working conditions, to the event attendees. The six of us each had a statement about Boohoo’s practices prepared and had planned to stand up on the catwalk descending from the panel area to shout these out one-by-one, then chant our way out of the venue.

Before the panel, a Boohoo employee and a representative of Source Fashion approached Venetia, reminding her that it was a “business event” and that questions would be taken at the end. Venetia later told me she felt like she was being singled out and told to stay quiet. We then noticed several security guards dotted around her.

Venetia asked the rest of us on WhatsApp if we were still going ahead – in my mind, there were no doubts. The additional scrutiny we were under reminded me of our purpose: to tell the truth in a way that we believe garment and warehouse workers didn’t have the space or privilege to.

Venetia led our disruption. She was quickly grabbed by three security guards and pulled off the catwalk at which point I wondered if we should abandon our plan and tend to her instead. But Yalda Keshavarzi, ambassador for Remake – an organisation campaigning for fair pay for garment workers – stood up and shouted her statement. We continued consecutively, but were removed too quickly to chant and exit together. “I didn’t notice them being that forceful until we were close to the entrance,” Venetia said to me as we debriefed after the event, showing me the bruise on her right arm. “I had to say to the man on my right, ‘please loosen your grip, you’re really hurting me’.”

Was I alarmed by the way Venetia was manhandled? Absolutely. Did I like being escorted out by security? No. But I was handled relatively gently and smiled as I neared the exit knowing we had executed our plan to stand in solidarity with workers.

After we’d all been removed, the moderator said: “Should every business be challenged? Absolutely. Do people have the right to free speech? Completely.” Sometimes when I watch it back and see the panellists smirking, I feel sick at the disrespect for the causes we are advocating for. Boohoo is doing the most to appear as though it cares about women, until a woman questions their ethics. “It is like the ribbon on top that ties everything so neatly together, isn’t it? What happened is a perfect demonstration of Boohoo’s hypocrisy,” Venetia says.

“Boohoo is doing the most to appear as though it cares about women, until a woman questions their ethics”

Outside the venue, I spoke to 21-year-old student Rosie Mott, who praised our protest. “I found it hard to not get involved myself, knowing that if I’d done so I would have sacrificed the opportunity to ask these challenging questions later on.” Rosie later asked the panel whether garment workers making Boohoo clothing in Leicester are paid a living wage, to which a Boohoo representative responded that they are paid the minimum wage. This would mean wages have risen since Labour Behind the Label’s 2020 report revealing wages of £3.50 an hour.

However, Boohoo Group did not provide us with evidence for wages paid to garment workers in our email correspondence following the panel. The spokesperson said that Boohoo Group implemented an Agenda for Change through which it “has made significant changes to strengthen [their] corporate governance, monitoring of [their] supply chain and driven internal changes such as the introduction of responsible purchasing practices.” He also added that “any accusation that Boohoo Group, or any of its brands, are tolerating the underpayment of people in our supply chain is not based on any of the available evidence.” Nonetheless, evidence of concrete improvement in wages and working conditions remains to be seen.

So, what now?

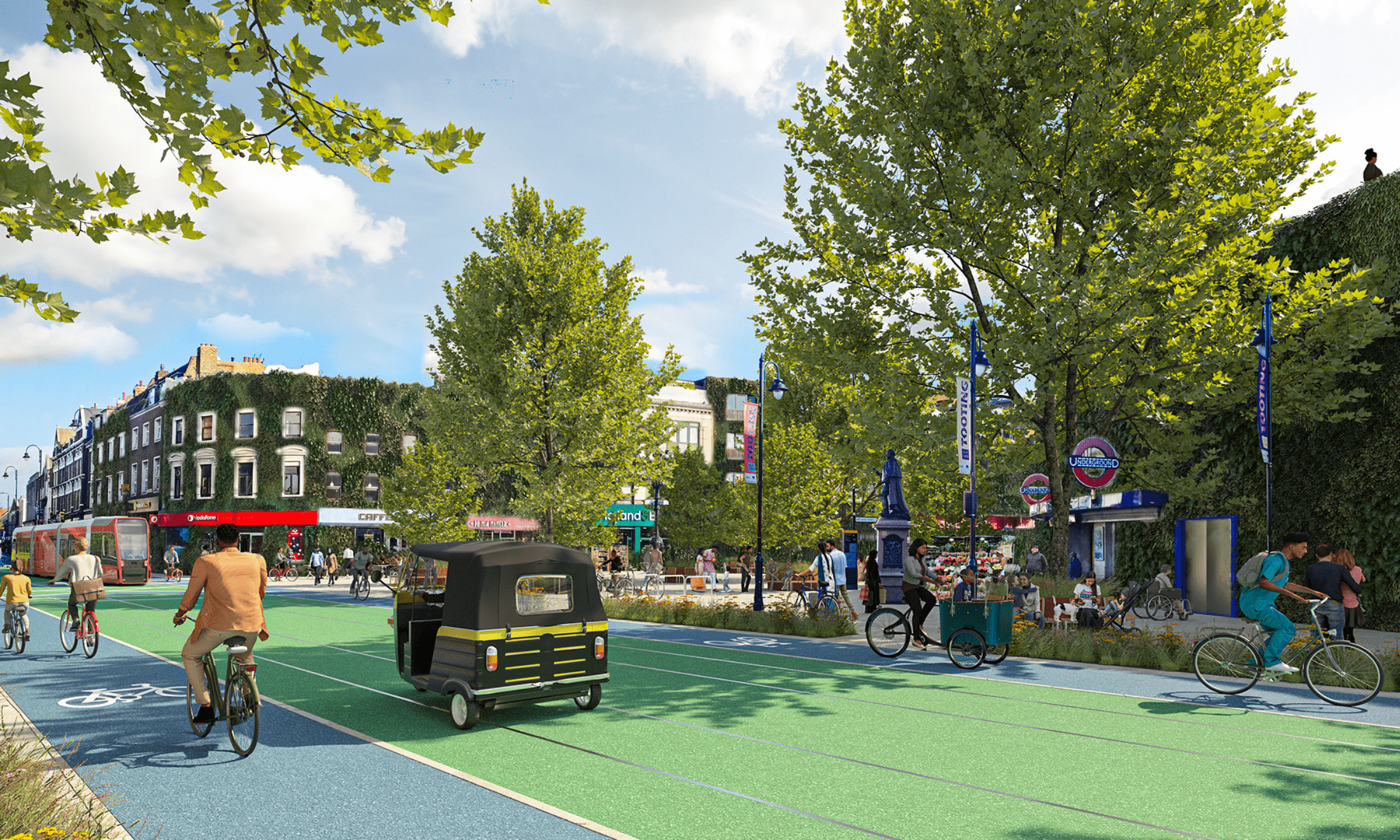

Some of us struck again on 7 March using social media to call out what we believe to be the hypocrisy of Pretty Little Thing hosting an International Women’s Day event at Mortimer House in London. We made digital assets about the brand’s controversial practices in their own branding and colours to share online alongside fellow ethical fashion advocates Besma, Sophie Benson and Brett Staniland. Activists later distributed fake gift cards with a QR code leading to claims about the brand’s alleged exploitative practices throughout Mortimer House.

There was no expectation that these two disruptions would get Boohoo Group to immediately change its exploitative business model, but they still matter. “Actions like [these] bring to light information that these brands are trying hard to hide. When more people get to know about that, it becomes more difficult for companies and governments to pretend it is not happening,” says 39-year-old Rebeca Dallmaier, a fellow protester and community organiser at Remake.

“Actions like [these] bring to light information that these brands are trying hard to hide”

Rebeca Dallmaier

The Remake-led Pay Up campaign consisted of an online petition and social media action to demand brands pay garment factories for orders they cancelled during the pandemic. The campaign built upon the organising of garment workers impacted by unpaid wages and resulted in around $22billion being paid to garment factories and workers across 25 brands. Even if it’s in the name of corporate greed and saving face, brands care about what their customers think of them. Yalda adds that “loud, bold, noisy action shakes [brands]. It shows that we are deciding where we put our money. It’s a way of reclaiming power.”

I want more than anything for power in the fashion industry to be redistributed, but until then, I will continue to find joy in using my power to stand in solidarity with garment and warehouse workers. As Ronaé Fagon, 31-year-old ethical fashion consultant and fellow protester, puts it, “these exploitative practices in fast fashion are demonstrating that some bodies are more valuable than others. So when we come together against that exploitation, a hierarchy of bodies isn’t present, and that feels really good.”

Use these resources to call out Boohoo for unethical practices.

For EU citizens, sign this petition to demand a living wage for the people who make our clothes.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.