Counsel Club: Meet the archivist reaching into the postbag of one of India’s earliest queer support groups

Pawan Dhall is ensuring that the work of the Kolkata-based Counsel Club isn't lost for future generations

Prishita Maheshwari-Aplin

26 Feb 2021

Pawan Dhall

Content warning: suicide

In 2018, India’s Supreme Court repealed Section 377 of the Penal Code, finally decriminalising homosexuality after a gruelling 20-year campaign by LGBTQIA+ activists. The 1990s marked an organised mobilisation of India’s LGBTQIA+ community, who challenged the colonial-era law; under the legislation they were threatened with up to a decade in prison if caught engaging in gay sex. It was within this fraught climate that the Counsel Club, one of India’s first LGBTQIA+ peer support groups, emerged.

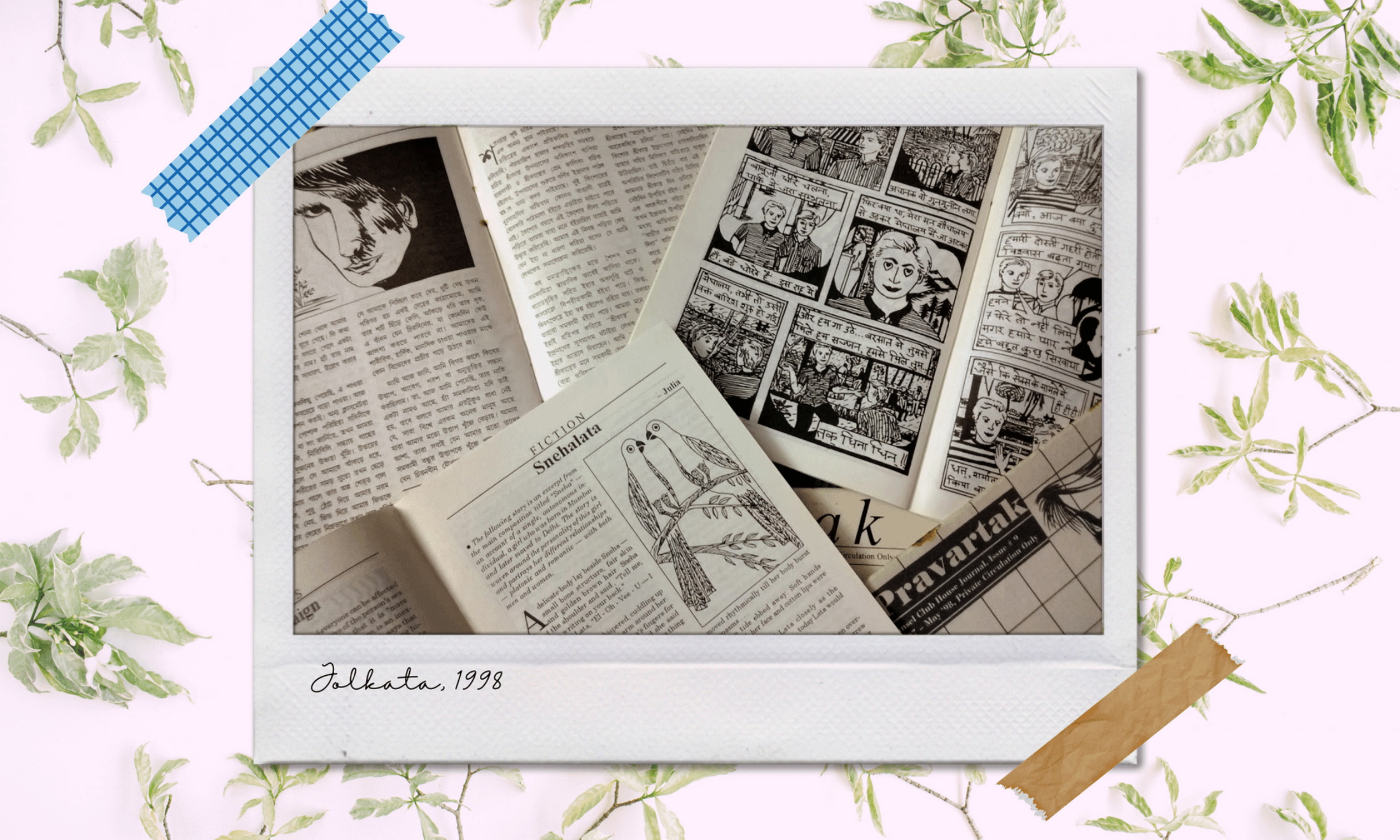

The Counsel Club operated between 1993 to 2002 in Kolkata, providing peer-to-peer support, both for the members and for the wider community. Along with offering tangible mental and sexual health aid through a letter-writing initiative, the club also published the house journal Pravartak (meaning ‘promoter of a cause’ in Hindi) twice a year. Pawan Dhall, one of the founding members, now runs an archive in Kolkata called Varta Trust – storing and researching materials produced and collected by the Counsel Club that shed light on the experiences of queer people in India at the time.

With the stories of countless members of the LGBTQIA+ community having been erased throughout history, it’s exponentially more important to preserve those we can access. I spoke with Pawan about his involvement with the Counsel Club and the archiving project currently underway.

Credit: Pawan Dhall

gal-dem: How did the Counsel Club work? What were your aims?

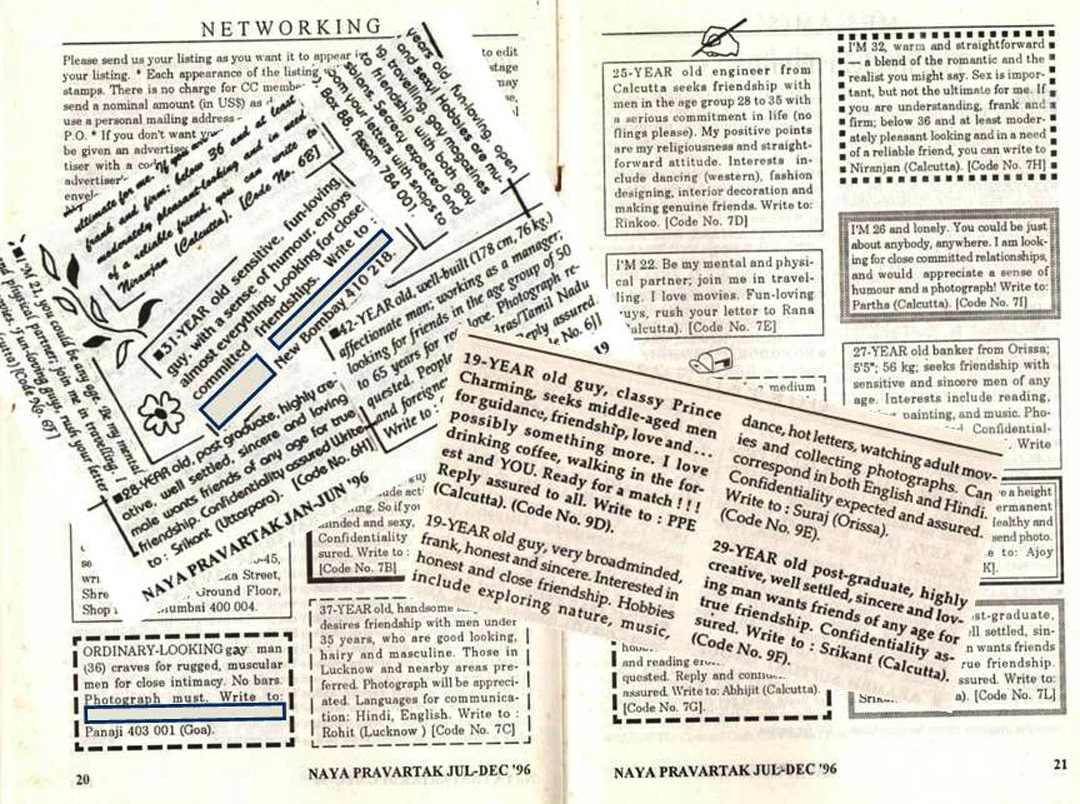

Pawan Dhall: Letter writing was our main mode of connecting with people before the internet. Our postbag number would be published, with a clear mention that we were an LGBTQIA+ support forum, in a number of publications – English and Bengali newspapers, queer and general interest journals, and international queer magazines, such as Trikone. We would also distribute a little brochure on the Counsel Club in the monthly meetings held in Kolkata. We started receiving a huge number of letters in 1994 from around the world, from individuals of all backgrounds, so we decided to host monthly meetings. We didn’t have an office or a drop-in centre in the earlier years, so most of the meetings would be in restaurants, parks or at one of the members’ workplace.

Primarily, our goal was community support. We were friendly counselors to one another; hence the name. We began with providing emotional support but also tackled human rights violations, people experiencing discrimination from their families, HIV diagnoses, and mental health issues. Even back then, we knew how important financial independence is for queer people so we were also trying to help others find employment.

Could you tell me a little more about the letters that the Counsel Club received?

Pawan Dhall: The majority of the letters we received were from men, which reflects the situation at the time for queer women: invisibility and even more oppression. It was obvious from the few letters that did come from women that they were taking a huge risk in writing to us. Most of the CC’s letters were written in English or Bengali, from individuals aged between 17 and 69 with a certain number of years of formal education; these would have been people from the lower-middle to upper class communities.

People often shared their isolation and loneliness; others were seeking advice on career choices, leaving home, relationships, sexual health, as well as support for gender reassignment surgery. Of course, we also received many letters of solidarity, saying “thank you for being there”. That’s how solidarity worked in those years – you were separated by thousands of kilometres yet you came together. Overall, it was a mixed postbag; a microcosm of India’s very poorly kept secret of sex and sexuality.

“Primarily, our goal was community support. We were friendly counselors to one another; hence the name”

Alongside letters, what else is stored in the archives today?

Pawan Dhall: The archives now hold around 3000 of these letters and emails – by the late 1990s, email communication had taken over. There are also greeting cards from the Counsel Club’s foundation day, records and files of the club’s activities, photographs of members, and a collection of journals from different parts of the world that are part of the club’s library. The library didn’t have a fixed place but would exist in a member’s house – their living room would be the meeting space and we would gather to read the letters in the adjoining bedroom.

The archive also houses copies of the house journal, Pravartak. I distributed this journal, which functioned like a newsletter, among friends even before the formation of the Counsel Club.

The main aim of the journal was to have another medium by which to connect with people and help them to express themselves. We always tried to have trilingual content in English, Hindi, and Bengali. That was criticised by some readers who said “we can read only one language, we’re missing out on what is written in the other languages”, but that would’ve just been too much work!

The maximum print run we had was 300 copies in 1998; this was exciting because it was stocked by three bookstores: two in Kolkata and one in Delhi. It meant we reached a wider readership beyond the group.

As one of the founding members, what did it mean to you at the time to be able to provide this community support?

Pawan Dhall: I had come out to my family in phases, but I was facing trouble at home, initially over my sexuality, then because I was publicly involved with a group like the Counsel Club. I felt isolated. So, my main motivation was the desire for a friendship circle – a family beyond the natal family.

For other founding members, the situation was much worse at home. When one of them came out to his parents, they tried to confine him at home. Nobody knew until we found out that he had attempted to kill himself. We were at our wits’ end; we had just started the Counsel Club and had no idea how to deal with that situation. He was eventually ok, but it was a big learning curve.

How did you learn to deal with these sorts of pressures amongst members?

Pawan Dhall: Much of the learning was on the ground; a lot of trial and error. Fortunately, the West Bengal Sexual Health Project, one of the first large scale government initiatives to address the HIV epidemic in India, was running in West Bengal around the time Counsel Club started. I attended one of their nine-day training programmes on counselling and sexual and mental health. We were also starting to learn about legal issues, particularly details of Section 377 and other laws around obscenity and vagrancy.

“Allen Ginsberg, the American poet used to visit Kolkata in the 1960s and attend the big queer parties hosted by local artists and activists.”

It’s amazing that you had access to this in the training. Along with holding these workshops, how were LGBTQIA+ people organising?

Pawan Dhall: This is actually something that we know more about now than we did then. At the time, there was a group called ‘Fun Club’, but it was more for meeting sexual partners. Other than that, social networks were largely built around cruising areas and certain markets in the city. People would also host parties at home. This was mainly the way queer people would connect with each other in an urban setting. In the rural context, networks would often be centred around gender non-conforming people from the Hijra and Kothi communities.

When we were doing research for articles, we read about Allen Ginsberg, the American poet. He used to visit Kolkata in the 1960s and attend the big queer parties hosted by local artists and activists. These were the submerged networks before the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the mobilisation began in the modern sense.

You mention informal connections between people living in rural areas and those who were gender non-conforming. Was there any interaction between your project and members of the Hijra or Kothi communities?

Pawan Dhall: Not so much during the existence of the Counsel Club – there was definitely a disconnect. We were aware of sexual reassignment surgeries, but the broader umbrella of “transgender” only came to be articulated in the late 1990s. The Kothi community had been organising amongst themselves for many years. If you trace queer history back in time, the rural networks were mostly Kothi networks. In the late 1990s, more Kothis joined the Counsel Club; through them we made connections with Hijra leaders.

However, there is a lack of intermingling even today. The Kolkata Rainbow Walk Pride, which is the oldest in South Asia, has Hijra participation but never in high numbers. There is a lot of mistrust.

What about the LGBTQIA+ people who migrated out of India at this time? What was their experience like?

Pawan Dhall: One of the things we learnt from the people who left India for the UK and US was that we have to be careful about where the queer movement is going. I had a Canadian friend who I met in Kolkata through Council Club in 1995 – he warned us that pride is far too commercialised in the likes of the US and Canada. It’s no longer about the movement but rather all about advertisement and sponsorships. I had to make a choice between upholding our values or popularity and a corporate takeover of our movement. I’m so grateful for this advice. In Kolkata Pride, we have always been very clear that there will be no banners, logos, patterns or anything from any corporation or NGO. This has been the policy since 2011 – the walk cannot be used to advertise how ‘broad-minded’ a company is.

Counsel Club officially ended in 2002. What happened to the members after that?

Pawan Dhall: By 2002 more people were coming out in the smaller towns and they didn’t necessarily want to travel to the big cities for a sense of community. In the early 2000s, Counsel Club had branches in four other cities – we felt a sense of responsibility for them but most didn’t last very long. We realised that it would’ve been better to provide people with training, moral support and help with fundraising, rather than setting up branches. They wanted their own freedom and we didn’t want to be colonial masters.

By that time, the Counsel Club was dissolving. However, within a few months there were a number of new groups emerging across the city, including Swikriti and Amitie Trust – many of these were founded by former members of our group.

What do you think that the queer community now, in India and around the world, can learn from these archives?

Pawan Dhall: The archives have a very strong contemporary value. When you have been through 25-or-so years of the movement, there is a point at which you turn and look back – it’s not just nostalgic, it’s political. If you forget the past you will repeat history, make the same mistakes again, and try to reinvent the wheel.

Today, if we were to campaign for an anti-discrimination law in India, we would need to show that discrimination has been a historical reality for the LGBTQIA+ community, and for that you need archives. You need to be able to show the ways in which people were suffering and negotiating for their lives. Yes, they were happy too, but they were experiencing loss of productivity, loss of wellbeing, loss of life. All of this is captured in the archives.