Photography via Instagram

For women and LGBTQIA+ people in the Caribbean, Western ideas of a liberal utopia hides an oppressive truth

Western culture sees the islands of the Caribbean as a liberal paradise. The real picture is far less inviting.

Zahra Spencer

27 Apr 2021

Content warning: abuse, sexual assault

For decades, weary travellers have flocked to the Caribbean in hopes of finding a piña colada-filled paradise. After all, aren’t the islands where you go to escape life’s dreariness and get your groove back? It’s your sunny, sexy break from the mundane, where rum is always flowing, women are scantily-clad, men are well-endowed and you can be enveloped by a permanent haze of weed.

For people living there, the picture isn’t quite as perfect. The portrayal of a socially progressive, hedonistic region is a striking oversimplification, considering the intense chokehold religious and social conservatism has upon the Caribbean. The reality is that across the region, marginalised groups like women and the LGBTQI+ community are subject to some of the most restrictive laws in the world, as well as antiquated, homophobic and sexist attitudes at all levels. Gender-based violence is a significant challenge and protests are ongoing in Jamaica after a spike in domestic cases and an alleged assault by a Jamaica Labour Party politician.

In February, Trinidad and Tobago was rocked by the brutal murder of 23-year old Andrea Bharatt, who was kidnapped on her way home, while using public transportation. Her death, which came only a month after 18-year-old Ashanti Riley was abducted and murdered en route to her grandmother’s house, prompting several days of nationwide protests and candlelight vigils.

The attacks only served to highlight the country’s lengthy gender-based violence crisis; in 2020 alone, 45 women across Trinidad and Tobago were murdered, (accounting for 13% of the country’s total murders) and approximately 416 women were reported missing. It’s a similar story across other islands. A recent survey of women in Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago measured the prevalence of gender-based violence between 2016 and 2019. The findings revealed that a staggering 46% of women in the surveyed countries had experienced at least one form of violence, highlighting the urgent need for reform across the region.

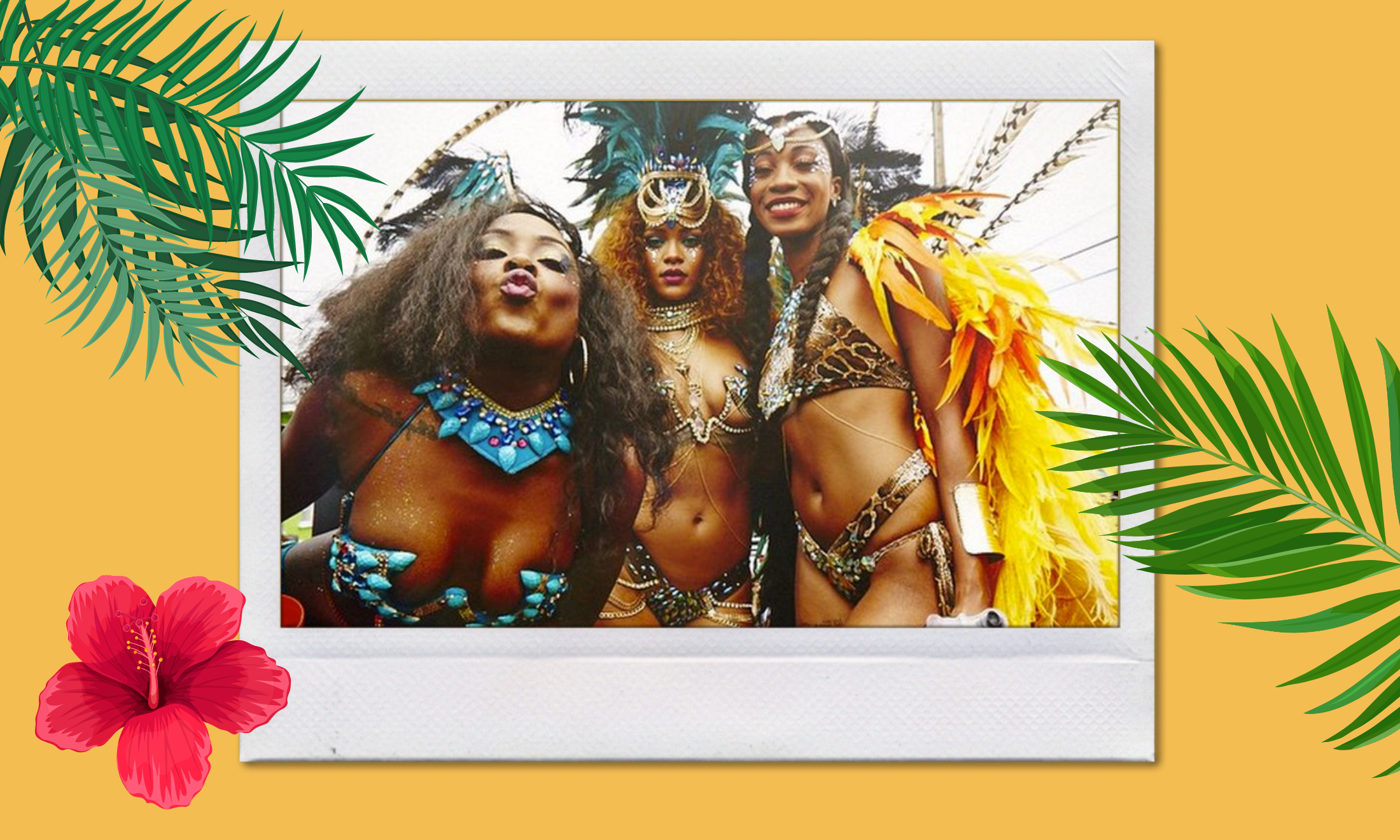

Casual misogyny is also common across the Caribbean, where women are subject to both objectification and attempts to control their bodies, while living beneath the veneer of a sexually liberated society. Just this past April, women’s groups across the region were forced to condemn the sexist Facebook comment made by the Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda, requesting that “pretty women” evacuating from neighbouring St Vincent due to the ongoing volcanic eruption be sent to Antigua. It can feel like the world’s strangest paradox; how can a region that encourages Carnival – where women are free to publicly adorn their bodies with as much or as little as they like, wining through the streets as part of a state-sponsored festival – also be responsible for maintaining a death grip on reproductive rights?

“For people in the West consuming depictions of the Caribbean, a sense of freedom is palpable”

Currently, there are precious few Caribbean nations that provide legal, unrestricted access to abortions. In Jamaica, an illegal abortion can result in life imprisonment. Although a recent study revealed that 22,000 illegal abortions take place annually, costing the government a hefty $1.4m (USD) per year, pro-choice activists in Jamaica are having a difficult time combatting the country’s widely-held conservative views, often fuelled by the church. One church leader went so far as to insinuate that the country’s high murder rate would only be exacerbated by the legalisation of abortion, thereby “forcing the hand of God” on the nation.

It’s not just a life-threatening lack of reproductive rights that Caribbean women have to confront; In similar need of reform is the Caribbean’s general anti-LGBTQI+ stance which continues to permeate through the region. Many islands identify as “Christian” or at least, “religious”, with a particularly socially conservative interpretation of Christian principles prevalent. Deviation from these is often met with backlash. In many cases, lawmakers fear alienating the conservative segment of the electorate, and as such, many progressive movements are at best, stalled and at worst, dead-on-arrival. For members of the LGBTQI+ community, it means the fight for equal rights can be an uphill battle.

In Barbados, generally regarded as one of the more progressive islands, the decision was recently made to legally recognise same-sex civil unions. Though the decision was largely a strategic one to encourage remote workers from countries where same-sex marriages are permitted – it was still seen as a step in the right direction. Yet this quickly spurred the country’s conservative population into action, with a number of church-led marches being held to protest the new legislation. Ultimately, the protests amounted to nothing but the intense backlash is likely the reason why the government has indicated that any further decisions on same-sex marriage would need to be put to a referendum.

In the case of nearby Bermuda, the country did hold a referendum on same-sex marriage after the British government encouraged the nation (a British overseas territory), to adjust its laws to be more in keeping with its own. The referendum, which took place in 2016, revealed that the majority of citizens were opposed to both same-sex marriage and civil unions. Despite this, in May 2017, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of legalising same-sex marriage. The ruling was so unpopular, however, that shortly after, the island’s legislature passed a bill overturning it (though allowing same-sex “domestic partnerships”), making Bermuda the first jurisdiction in the world to reverse its stance on same-sex marriage.

Colonial-era laws which criminalise ‘buggery’ and acts of ‘gross indecency’ between men, also litter the statute books of many an island across the Caribbean. While these laws are very rarely enforced, their continued existence serves as a tangible example of the continued marginalisation of the LGBTQI+ community. Human rights organisations have repeatedly highlighted the dangerous and harmful nature of these anti-LGBTQI+ laws which encourage prejudice, discrimination and in some cases violence. Yet many islands have been slow to implement any reform.

“The region’s stifling social conservatism is being continued apace by new masters”

Nevertheless, West Indian activists are continuing to challenge legislated homophobia around the region. In 2018, LGBTQI+ activist Jason Jones took the Trinidad and Tobago government to court over Section 13 of the country’s “Sexual Offences Act” which criminalised consensual same-sex intimacy. The laws were deemed unconstitutional, resulting in a landmark decision for the LGBTQI+ community in Trinidad and Tobago.

In the Cayman Islands, Chantelle Day and Vickie Bodden Bush are in an ongoing legal battle with the Caymanian government, after being refused a marriage license in 2018. Like Bermuda, same-sex marriage was first legalised after the Grand Court ruled in Bush’s and Day’s favour, but the ruling was subsequently overturned by the Cayman Court of Appeals. As of the time of writing, the case has been elevated to the Privy Council in the UK, which continues to be the highest court in the Cayman Islands.

On a further positive note, the past few years have seen a rise in gay pride celebrations throughout the Caribbean, with countries like Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Bermuda, Saint Lucia and Curacao all hosting events. LGBTQI+ activists in many of these territories see the increased prevalence of these celebrations as indications that the staunchly conservative region is slowly moving in a positive direction.

While it is indeed true that much of the Caribbean’s uber-conservative laws are colonial hangovers, the region’s stifling social conservatism is being continued apace by new masters. The rest of the world aid this, by refusing to engage with the region as a real place with real people who experience real problems, and not solely as a backdrop for an Instagram is often reserved primarily for Western travellers. For women and LGBTQI+ people, the experience is often far more oppressive. In order for there to be a real reckoning as it relates to civil rights in the region, the vibrancy and allure of one side of the Caribbean, cannot continue to overshadow the darkness of the other.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?