#StopSIM: NHS England are bringing police into mental health services. What could possibly go wrong?

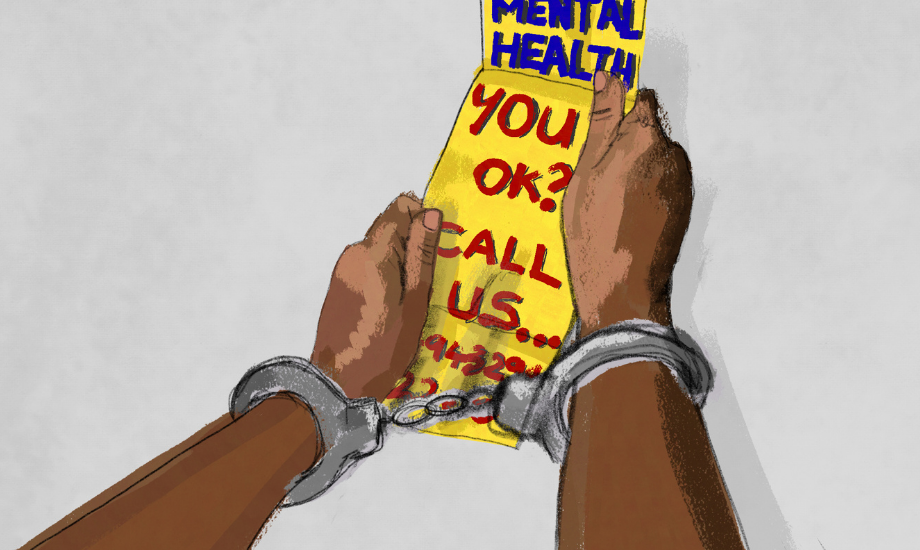

A "transformative" new mental health model wants to bring police into support services. Campaigners say it will criminalise the most vulnerable.

Kimi Chaddah

14 May 2021

Diyora Shadijanova

Content warning: detailed accounts of police violence, suicidal ideation

Last month, a flurry of posts began appearing on social media, detailing experiences under a new scheme. They contained worrying reports – people in mental crisis involved in the scheme would call support services, only to be threatened with prison if they contacted the likes of an ambulance.

These posts outlined the experiences of “high-risk” individuals on the receiving end of the Serenity Integrated Mentoring (SIM) scheme – a new mental health support model, currently being adopted by NHS England. It works by assigning people in distress – typically “high intensity users” of emergency services or those perceived to be at high risk of suicide and self-harm – to mental health professionals and police officers to assist with challenging cases.

Police officers, or “High Intensity Officers” (HIOs) are given primary responsibility for behavioural management, placing pressure on individuals to reduce “high-cost behaviour” and stop “demonstrating intensive patterns of demand”. Police may ensure compliance using threats of legal action, such as Community Behaviour Orders. Conflating the “best results” with a reduction in 999 calls, demand for services and hospital admissions, SIM answers the crisis with police intervention rather than holistic patient support.

The scheme is in full flow. Hailed as “transformative”, it was originally piloted on the Isle of Wight in 2013 and is in the process of being rolled out across England. Currently, SIM is in operation across London and is supported by the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust which treats more than 45,000 patients in South London communities.

Despite claims of reforming the mental health system, mental health campaigners say SIM symbolises the creeping encroachment of police powers and the stigma deeply embedded within mental health care.

A leaked page of staff comments from the original SIM pilot evidence worrying cruelty from NHS staff towards service users, including seeming support for ‘scaring’ users into not repeatedly contacting the service for help. “I dislike her less now”, comments one staff member, speaking about a patient. “We can tell a service user that consequence X could happen. Police tell the same person that consequence X will happen”. Users can be threatened with prosecution or prison if they continue calling for aid.

SIM’s opponents say that the police presence is designed to be “coercive”, giving doctors and nurses the “confidence” to not treat patients in ways they would have done previously – such as keeping the individual in the emergency department for observation, pursuing the individual if they decide to discharge themselves and requesting the police to conduct a welfare check at home. The creator of SIM, ex-police sergeant Paul Jennings, claims the root of unsustainable demand lies in over-dependence and behavioural issues, rather than the underfunding and inequalities that have crippled the system.

Questionable methods

At the forefront of efforts to combat the advance of the scheme are StopSIM, a coalition of users with lived experience of mental health services. StopSIM has questioned the methodology behind the scheme, which lacks evidence and trauma-informed input from service users. The coalition has also raised concerns about the sharing of medical information with the police without patient consent, which, they say, is likely to have a “disproportionate impact on ethnic minorities […]”. History backs this prediction up; ethnic minority communities are less likely to approach healthcare services when police and government agencies are involved.

Post-Windrush, one report found the scandal led to people from ethnic minority communities being afraid to seek cancer care during the pandemic, while migrant survivors of domestic abuse often are unwilling to seek help from police, social services or authorities for fear of Home Office involvement. Meanwhile, research commissioned by NHS England revealed patients seeking mental health support from Black and ethnic minority backgrounds are disproportionately subject to physical restraint and coercive forms of treatment, instead of being treated with outpatient and holistic methods.

Now SIM, say activists, entrenches stereotypes they’ve worked for years to eradicate; self-harm is likened to “manipulative behaviour” and people with ‘personality disorder’ diagnoses are told to “take responsibility” for their distress, to reduce engagement with services. The scheme espouses the belief that people who express suicidal thoughts, but don’t die, are not genuinely suicidal and thus not an area of concern, placing them in a category of people who attend A&E for “false, malicious or unnecessary reasons”.

Questions also surround the qualifications of those behind the services; the High Intensity Network, responsible for SIM, claims part of its legitimacy via its supposed work with Mental Elf, an evidence-based blog. Mental Elf says it has never worked with the organisation.

“SIM echoes the ideals underpinning the infamous Victorian ‘madhouse’ Bedlam where, instead of receiving intervention, patients were criminalised for their mental illness”

While existing mental health crisis plans involve the police if a person is deemed at risk of harming themselves, SIM is a step up in the state-sanctioned criminalisation of mental illness. The scheme also reinforces the individualisation of mental health issues, rather than promoting treatment through well-funded mental health support networks.

SIM echoes the ideals underpinning the infamous Victorian ‘madhouse’ Bedlam where, instead of receiving intervention, patients were criminalised for their mental illness. The vilification of “high intensity users” embedded throughout SIM plays into a wider trope of people who access emergency mental health care regularly being mocked as “frequent flyers” (a phrase which makes an appearance on a presentation about SIM), “regular attendees” and “repeat callers”.

Joyce Kallevik, director at user-led charity Wish, which works with women with mental health needs in prison, hospital and the community, tells gal-dem: “We have already seen criminalisation of suicide in a number of areas, with people sent to prison or fined for attempting suicide. This isn’t something that has originated from the SIM project – activists have been shouting about this for quite some time. However, we worry that with the rollout of this model across the country, criminalisation will increase. This isn’t acceptable.”

“There are also a high number of women entering (and remaining stuck in) the criminal justice system who have experience of abuse, trauma, and poor mental health, all of which is exacerbated by prison. We should be doing everything we can to increase community-based services that divert women away from prison – which criminalising [suicidal ideation] is simply not going to do.”

Expansion of police powers

The rollout of SIM has also heightened fears for people of colour trying to access mental health services, who are likely to be at further risk from the involvement of police.

“The police have no place in ‘supporting’ Black people – or any people – in a mental health crisis,” says a spokesperson for social justice organisation Black Lives Matter UK.

“We know that police punish individuals for systemic problems, and the power to do so is only expanded under SIM. The sharing of records between mental health services and the police invites more state surveillance into our healthcare system and makes seeking support actively unsafe for Black people, sex workers and other marginalised groups.”

Police treatment of people of colour is informed by racial stereotyping and past police involvement with vulnerable individuals has proved deadly. In 2010, Olaseni Lewis, 23, died at Bethlem Royal Hospital after police brutally restrained him for a prolonged period. Seni, as he was known to friends and family, had gone to the hospital – nicknamed ‘Bedlam’ – voluntarily, to seek help. Police and medical staff – who had initially called officers in on a report of criminal damage – did not intervene when Lewis became unresponsive after being subjected to “violent restraint”. At the inquest, the jury found that the “excessive force, pain compliance techniques and multiple mechanical restraints” were disproportionate and unreasonable.

Meanwhile this month, Metropolitan police officer Benjamin Kemp was dismissed from the force after a disciplinary hearing heard he had hit a vulnerable 17 year-old Black girl 30 times with his baton as she approached his police car for assistance.The teenager, who has learning disabilities, had run away from a group walk after becoming distressed. Having flagged down a police car to request help, the teenager told officers she was a vulnerable person with mental health problems. Subsequently she was handcuffed, pepper sprayed and hit with a baton. These are just two cases out of many where policing grounded in racism and the criminalisation of people with mental health conditions combine to produce a deadly and traumatic outcome.

SIM aligns with current Tory government strategies to position the police as the answer to social issues, and expand policing powers under the guise of protection. Campaigners say the real solution is funding.

An alternative approach

“The SIM scheme is an imperfect attempt to sort out an issue which can only really be solved with more resources and funding,” explains Natasha Devon, mental health campaigner and founder of the Mental Health Media Charter.

“Our focus should be on resolving the problems which led to a perceived need for the scheme in the first place. A person who has reached the stage of mental health crisis where police intervention is deemed necessary has likely been on a path where better resourced services could have stopped them getting [there]. I don’t think involving law enforcement is the answer,”

Mental health issues, adds Natasha, are often “rooted in inequality”, with minority groups encouraged to individualise their struggles as a problem with their brain, rather than with the structure of the society they’re in. So what are the alternatives to SIM?

Speaking to gal-dem, a spokesperson for the National Survivors Users Network (NSUN) said: “We would like to see compassionate responses to mental distress from services, with no place for coercion or the criminalisation of distress in the form of threats of legal action and police involvement, and with acknowledgment of needs unmet by the current mental health system.”

As for action in the short-term, StopSIM is calling on NHS England to halt the rollout and delivery of SIM with immediate effect, as well as other interventions associated with the High Intensity Network (HIN). They also want an independent review and evaluation of SIM to take place, in regard to its “evidence base, safety, legality, ethics, governance and acceptability to service users.”

In response to concerns raised by StopSIM, NHS England’s National Mental Health Director said the organisation is not “formally endorsing” the spread of the programme. StopSIM say the reply is “reassuring’ but the action promised by NHS England does not reflect the “urgency” of the issues highlighted.

If you would like to support the campaign to StopSIM, follow these two steps:

- Sign the StopSIM Coalition’s petition to halt the rollout of the scheme here

- Write to your MP to express concern using this template letter

This piece was updated on the 14 May 2021 to acknowledge the StopSIM campaign had received a response from NHS England and to remove specific references to a social media thread detailing personal experiences of SIM.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?