Laura Mvula is done filtering her sound – and herself

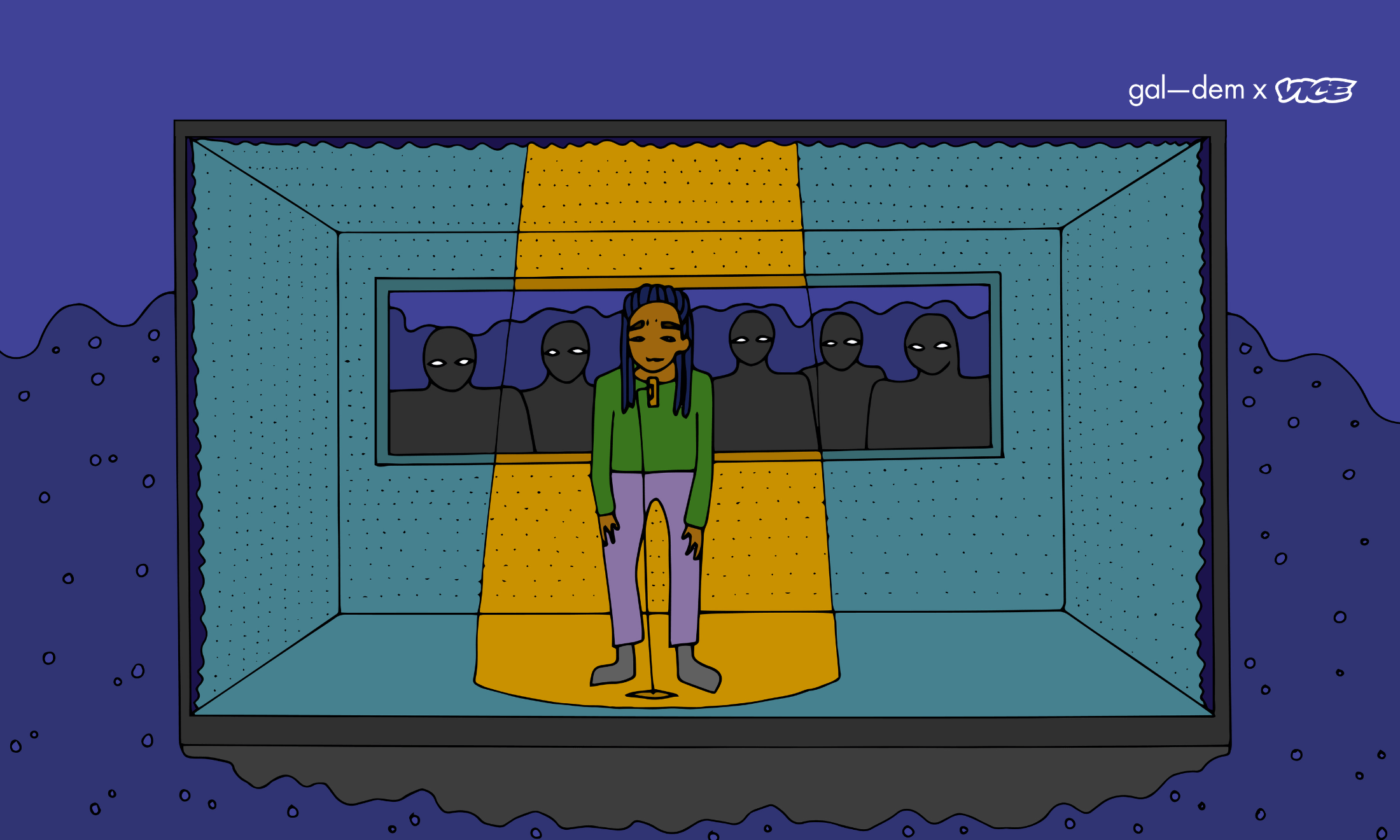

Following the 1980s boldness of her third album, Pink Noise, Laura Mvula reflects on writer’s block, self-image and the realities of being a Black woman in the British music industry.

Kayleigh Watson

03 Sep 2021

Dawbell Press

“I had, like, one date with this guy from Bumble. I remember when we were texting, and I was in the middle of the record – it was in lockdown, so we couldn’t meet. He was asking me about what the album vibe was and I said ‘1980s’, and he said, ‘I hate the 1980s’. And he’s not the first person.”

There is a pause as my personal shock and disgust are audible over the questionable quality of our Zoom call; after all, what heathen would profess to not love 1980s music? It is a sound that is newly synonymous with Laura Mvula who – in returning with her third consecutively Mercury-Prize-nominated album Pink Noise – has taken critics and fans by surprise with a record that is rich, bold and undeniably steeped in 1980s influence.

“I think it’s quite divisive as an era,” Laura continues. “There are quite a few people that passionately hate it. They hate synthesizers, they hate the buoyancy, the boldness – but for the same reason there are a lot of people that passionately love the same thing.”

“I feel like I’ve come out of a closet and I can enjoy being my own artist, truly”

Growing up in a family that adored the era meant that Laura held an innate affection for the time. Her father, particularly, was a massive fan of Earth, Wind and Fire whose sound she proclaimed she intended to emulate with Pink Noise (“I think I deliberately said things that seemed outrageous to me in order to give myself a goal and also just to silence people so I could get on with it”).

The journey to Pink Noise has not been a simple one. First emerging with her debut Sing to the Moon back in 2013, then releasing her 2016 sophomore album The Dreaming Room, Laura has been down many a meandering and tumultuous path, spanning a self-critical mind and creative anxiety. Though her two collections of soulful baroque have collectively earned her a pair of MOBO Awards and an Ivor Novello, as well as those aforementioned Mercury nominations, this time around, she somehow felt more pressure.

“I thought, why is it this album? How can I be someone that makes Sing into the Moon and The Dreaming Room, and now I don’t have any inspiration or motivation to make [anything]?”.

Laura recalls a conversation from years prior with Bat For Lashes’ Natasha Khan, who was similarly incapacited at a time where Laura had no real perspective on the issue. “I was so terrified that this was more than writer’s block, that this was me quitting,” Laura explains, “I didn’t know how I didn’t know what to do. It’s okay when you’ve got some answers, like Natasha was resourceful and spoke to people like [Radiohead’s] Thom Yorke. I just sat in my flat until I forced myself into a weird prison. I gave myself sort of an ultimatum but also this almighty pressure. ‘Safe Passage’ was the first song I wrote here at home and I knew everything was going to be alright, but to get to that point felt like an eternity.”

As the album opener for Pink Noise, ‘Safe Passage’ is a yearning and understated ode to navigating such pressures and grasping for stability at the other side. “No need to make it harder than it already is,” Laura sing-states, matter-of-factly; “I’m noticing a pattern that once I have one piece of music that is the DNA of a whole body of work, I lose the fear about the rest of the project”. A contributing factor to her change in perspective was producer Dann Hume who would encourage her to set aside ideas and return to them with a fresh ear, something which she describes as “an alien experience”.

“I think I have known what it is to feel so scared about putting a foot wrong that I haven’t been able to put pen to paper,” she explains, “But I think I needed to experience that to now enjoy what’s been such a freedom. I feel like I’ve come out of a closet and I can enjoy being my own artist, truly.”

Laura recalls being referred to as “underrated” due to the unique sound of her first two albums. “I got used to all those taglines: ‘she’s in her own lane’, and ‘she’s created a genre that is new in itself’. But the moment I stepped into this nostalgia and these 1980s references that are very obvious, that takes a different kind of conviction and courage from me, which has meant that I am in turn much more confident and not so concerned anymore.”

One of the most left-field moments of Pink Noise comes from ‘What Matters’, her soft, comforting duet with Biffy Clyro’s Simon Neil that sprung from a bit of pushback when her label suggested the feature come from a rapper. “I was like, no, I’m not gonna do that thing, all because I’m Black you just wanna pair me with another Black person and just force into some false relationship. It’s weird”. She told her management that she was looking for a youthful yet seasoned rock voice reminiscent of Peter Gabriel, when someone suggested Neil. “I love the song so much. He was so kind. He was so awesome about it. [When] I got the file sent to me, I listened at home in my living room and cried”.

“When I entered the scene, I was told that ‘you know there’s only room for one Black female artist at a time Laura, you know that right?’”

Airing her opinion is another marker of confidence for Laura, who has experienced the weight of presumption as a Black woman in the music industry. “When I entered the scene, I was told that ‘you know there’s only room for one Black female artist at a time Laura, you know that right?’”

She reflects on having a relationship with most of the Black women singer-songwriters in her sphere, and the unwritten rule being a known thing. “We come up with that on our shoulders, like ‘don’t expect whilst that female is at the top, there’s room for you’ – and I accepted that.” She laughs, “With Sing to the Moon, I was just like, okay, I’ll just be in my corner over here, sit at the piano and do my thing and it will be fine.” Except, of course, it’s not, and after spending time working in the US, artists, friends and fans made her realise that she could nurture confident self-worth without being false or arrogant. “It’s taken a minute to go, ‘this is what I am, and it’s fucking amazing’”.

The surprise in public reaction to her change in sound on Pink Noise has also been interesting for Laura to witness but, she says, this present iteration is who she has always been – only this time around she’s shedding her exoskeleton and baring her authentic self for all to see. “I’m not scared of what will happen if you see who I am because you don’t hold the power. Journalists used to write the most sort of systemic racial shit,” she says, “They would say ‘classically-trained Mvula’, which is just a way of apologising for me being there. It’s like ‘it’s alright, she’s classically-trained, she has a right to be here’ – and I played up to it. I thought it was a thing, like ‘look, here’s this Blackie that plays violin’.”

This realisation that she was complicit in perpetuating those public perceptions of herself was a hard pill to swallow. “I had to do a lot of soul searching and be prepared to throw off that façade. I’m realising it’s a long road and Pink Noise has kind of been like a balm,” Laura adds. “It’s a healing thing that helps me in the struggle. I feel armed with it, and I feel ready. I definitely make no excuses anymore.

“I’m not ‘classically trained Mvula’, and I’m not ‘all of a sudden, sexy, Mvula’. I’m just me, and I would just hope that other young creatives coming up feel empowered. And if anything, I hope they just look at me and go, okay, she’s done that, I can do anything.”