Solidarity in silence? Why muting artists in support of music industry abuse survivors is complicated

Speaking to industry experts, Ray Sang explores the nuanced questions around whether not pressing play on the work of alleged abusers can make a difference.

Ray Sang

27 Jul 2022

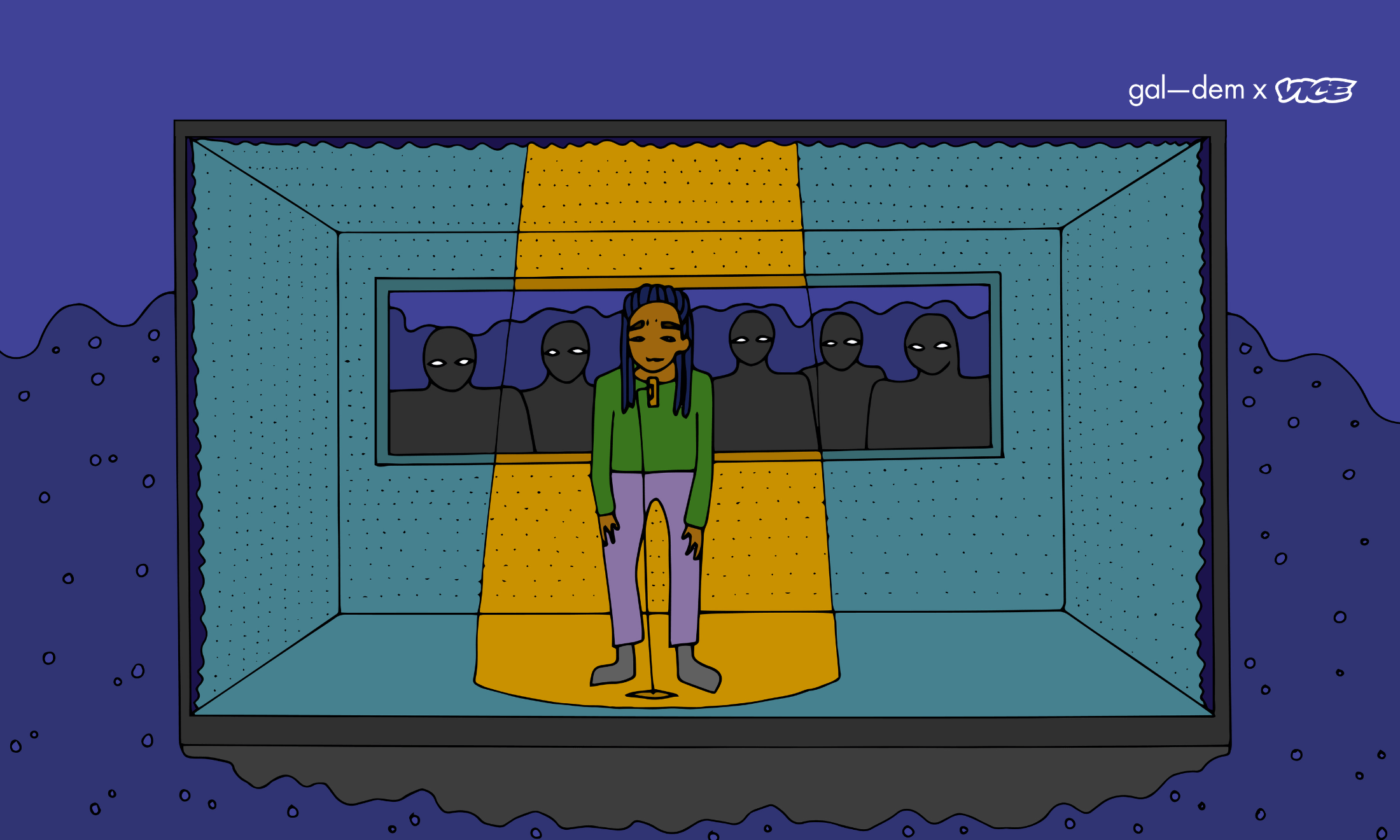

Aude Nasr

This article is part of Open Secrets, a collaboration between gal-dem and VICE that explores abusive behaviour in the music industry – and how it has been left unchecked for too long. Read gal-dem’s Open Secrets articles here, and read VICE’s Open Secrets articles here.

Content warning: This article contains mention of abuse.

In October 2021, rap artist Octavian broke his silence following allegations of abuse to announce he was quitting music for good via Instagram.

The rapper parted ways with his label in 2020, when his album release was scrapped following his ex-girlfriend speaking out about his alleged physical and mental abuse; which he staunchly denied. A year on and still no new music in sight, it seemed that lack of engagement with his music and persona from both consumers and the music industry at large drove him to this decision, indicated by his caption “Innocent or not doesn’t matter in my city”. In December, taking a more direct approach, he released a new song using the hashtag “fuck cancel culture”. The track received minimal engagement, with little coverage or discussion among media and consumers alike.

When news of Octavian’s alleged abuse came to light, Pattern Publicity ceased all work with him and Radio 1 and 1Xtra removed his tracks from their stations’ playlists. This became one of the more public examples of gatekeepers choosing to take action against abuse. But just how effective is the collective ‘cancellation’ of musicians alleged to have perpetrated harm in showing solidarity to survivors, beyond a display of public unity?

gal-dem looks at the financial implications of refusing to press play on an artist’s work, the challenges that pose a threat to the effectiveness of muting, and the wider responsibility of media publications reporting on these issues.

Controlling public consumption

According to Midia Research, there are approximately 487 million consumers currently registered on music streaming services across the world. 70% of the money generated from these platforms goes to rights-holders, which covers everyone from major labels to the independent artists who release their own music. Those funds are then split between everyone involved in making the song.

In light of this, it is not difficult to see how large portions of society refusing to engage with an artist’s work could affect a musician’s bottom line. Whether it should be left to consumers to mobilise themselves to do so, or whether the onus should be on the radio stations and streaming platforms, to limit access to the music of abusers, opens up an entirely new conversation.

“It is not difficult to see how large portions of society refusing to engage with an artist’s work could affect a musician’s bottom line”

In 2018, Spotify made the decision to stop promoting or recommending music by artists whose content or conduct it deemed to be offensive. Under this policy, any artist who fits that criterion would be removed from all official playlists and recommendation features on the service. While this doesn’t quite equate to censorship as the music is still accessible to those who want to stream it, it did indicate some willingness from the platform to show solidarity from a curatorial perspective.

Three years on, streaming giant YouTube took a much firmer stance in the wake of R Kelly’s convictions by removing his channels completely from the platform in October 2021.

In this case, music platforms embracing their role as gatekeepers and actively limiting access should be regarded as a step in the right direction, but consideration for the wider impact of these actions and their replication in synonymous circumstances must also be made. The criteria used by platforms when identifying and subsequently removing the music of abusers should be simple, easy to follow, and objective, so that when taking similar actions in the future the lines are clear and impartial.

Music publishing and royalties consultant Shauni Caballero suggests that other collaborators on a ‘muted’ song should be considered too. “Is it fair for the other collaborators involved, where proven to be innocent, to have their sources of livelihood stripped away also?” she asks. This question requires a balance of multiple interests, including the wellbeing of the survivors, and earning capacity of those being propelled into the firing line as collateral.

The primary way for collaborators to earn a living for their contributions is through royalties. Removing the music from streaming platforms entirely severely limits their opportunity to do so. It could be for this reason that while both YouTube and Spotify were vocal about their lack of support for abusers in the industry, neither one was prepared to completely remove the music from their platforms. Arguably if the music remains accessible, albeit much harder to find, it sparks a question as to whether abusers can truly be muted when their songs are still discoverable and able to be played. It is therefore difficult to evaluate whether this attempt at showing solidarity can be actualised without first looking at its monetary implications.

Taking control of the purse strings

Muting is so often seen as a way to show support to survivors because of the crippling effect it can have on the alleged abuser’s finances. “The majority of an artist’s income is going to come from radio plays, streams and sales. By removing them from these platforms and not having them on these big playlists, it significantly reduces their income,” explains Shauni.

This would suggest that muting is a three-pronged approach involving consumers, radio DJs, and wider gatekeepers such as the streaming platforms. Within music, every time a composition is copied, reproduced or played in public, the rights holders and writers of that work will be paid.

The rights holders are usually the record label unless the artist is independent. Finding out who the rights holders and writers are is a click away, within apps like Spotify and Apple Music, and often indicated by the words ‘source’/ ‘under exclusive license to’ and ‘written by’ respectively. Following the chain of ownership when it comes to royalties would appear to be very simple, even for the average consumer. However, the use of samples can make this complicated, as exemplified by the uproar surrounding Drake’s album Certified Lover Boy.

“Producers themselves also have a responsibility to be more selective with the works they choose to keep in circulation through the use of their samples”

It credits R Kelly as co-lyricist for the track ‘TSU’, and while the singer does not appear on the track, one of his songs can be heard faintly in the background of a sample featuring OG Ron C talking. In order to use the speech, Drake’s producer had to license the song and subsequently credit R Kelly.

This outcome would suggest that producers themselves also have a responsibility to be more selective with the works they choose to keep in circulation through the use of their samples. Failure to do so could result in the complete unravelling of any positive impacts generated from actions of muting, by giving the music an opportunity to be rediscovered and engaged with once again – and, crucially, still giving money to the alleged abuser.

Let’s talk about the media

Given the clear threats to the effectiveness of muting, it is clear that it will take much more than one cog acting in isolation to remove abusers from the prominent positions they hold within the music industry as entertainment journalist and Pink News producer Chandni Sembhi shares. “While muting artists is an effective way of showing solidarity to survivors, it can’t be the only way. Accurate reporting and taking a stand as a publication would also be effective.”

But what does this look like in practice?

According to a statement from charity OnRoad Media, which is currently supporting people who have lived through sexual violence and domestic violence via their project Angles, it can be as simple as journalists and publications asking themselves the following questions: What is the purpose of this piece? Why am I writing this now? What do I want people to feel, think and do after reading the article? The answer to these questions should then form the basis of the way issues are discussed moving forward.

“There’s a tendency in the media, especially when it comes to allegations of sexual misconduct from high-profile individuals, to question and scrutinise the intent of the victims coming forward more than the perpetrator’s acts,” says project coordinator Chiara Varè.“This is a form of victim-blaming. It is less frightening to think about how to help people control themselves than it is to name the root causes of sexual violence or see all the factors that create environments where sexual abuse and assault can happen.”

Actively committing to accurate, authentic and sensitive storytelling around these issues, Varè stated that it’s important to move the scrutiny away from the survivors and shift the focus towards the structural issues at play. Doing so drives the conversation towards the steps that can be taken to create actual change and the role each of us has to play within that.

9bills music editor Maria Ibitoye stresses the importance of being sensitive throughout the reporting process itself. “Start off with a trigger warning and telling anonymised stories…maybe getting input from a professional who can give general help so they [survivors] are not just reliving their trauma [when giving interviews] but also entering a door that can start helping them too.”

“One only has to look to the support Octavian received in the comments of his Instagram post, and to those taking to the streets to march in support of R Kelly during his trial”

Good quality reporting and muting can be effective as methods of showing solidarity, but neither offsets the fact that fans may continue to engage with an artist’s work, even when allegations of abuse come to light. “No artist is ever fully muted anywhere on the internet,” NME music journalist Kyann-Sian Williams says. “In cases where the abuse hasn’t come to a conclusion or there’s no concrete end to the case, many will [continue to] find [the music].” One only has to look to the support Octavian received in the comments of his Instagram post, and to those taking to the streets to march in support of R Kelly during his trial, to see that.

We’ve explored the big, industry-wide issues, but not every action has to be large. There are also ways of showing solidarity on a much more individual level. It can be as simple as taking the time to educate yourself, watching documentaries like Music’s Dirty Secrets, following the cases, and talking about these issues in your group chats. On a consumer level, muting artists may be the easiest way for listeners to feel like they are contributing to change given its potential to limit an abusers source of income. However, looking at the music industry more widely, restricting access to the work of abusers is only one element of a wider strategy of solidarity. Muting, supplemented by a more holistic approach to reporting, which focuses on challenging broken systems rather than scrutinising survivors and vilifying individual abusers as bad eggs, perhaps offers a more sustainable means of showing support.

For a full list of resources related to this article and the Open Secrets Series, visit our Open Secrets Resources page here.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee