Unveiling Keisha The Sket

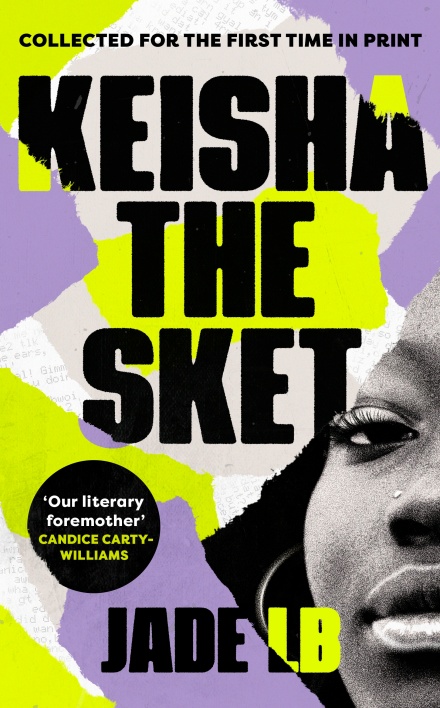

The anonymous author is ready to share her own story as Stormzy’s publishing imprint adds the 00s Bluetooth viral tale to Black British canon.

Adwoa Darko

14 Oct 2021

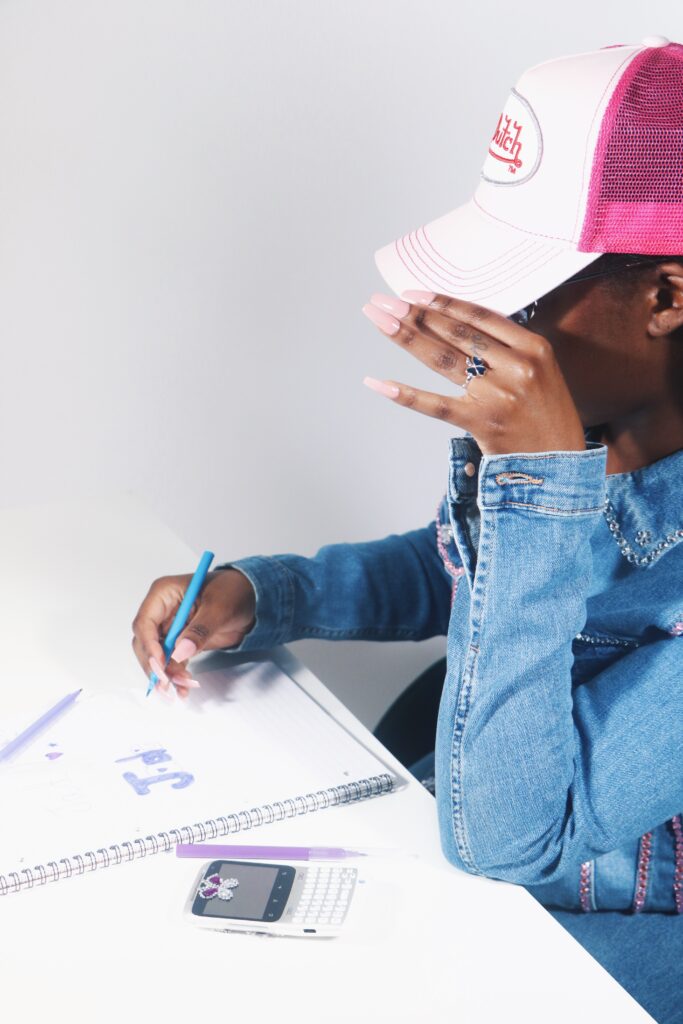

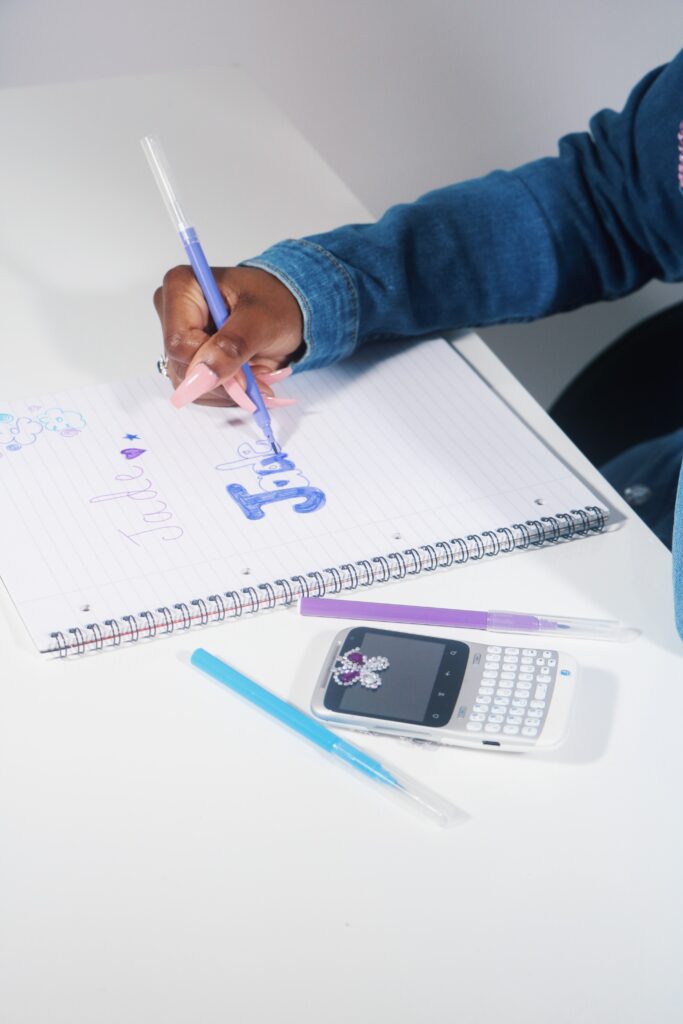

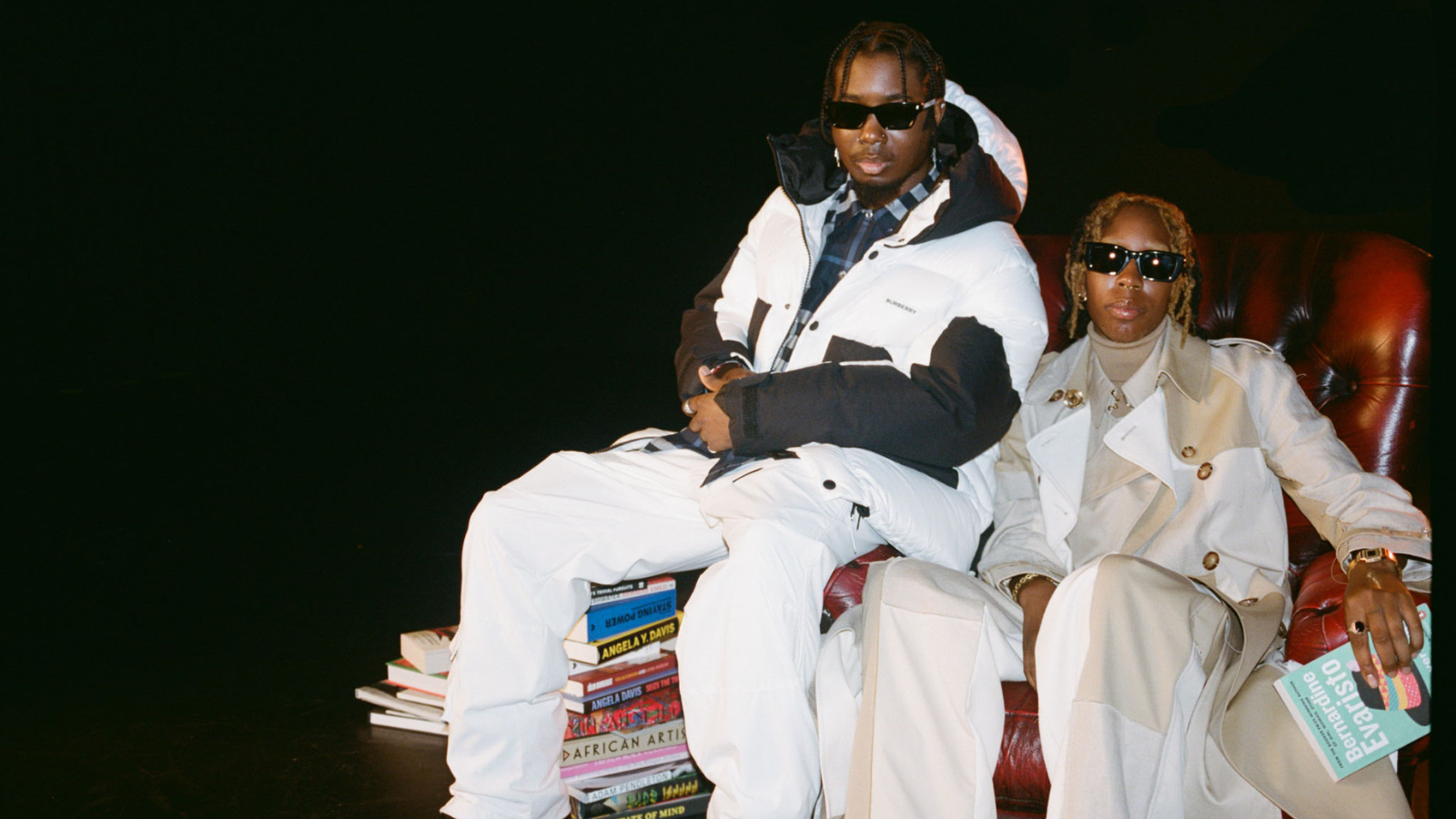

Jade LB photographed by Jamila Hardy, styling by Amii McIntosh, collage by Karis Pierre

“Oi Adj, have you read ‘Keisha The Sket’?” My Year Seven friend was shaking with excitement. Sweeping my pick-and-drop bang off my face, 11-year-old me was confused. “Yeah, let me Bluetooth it to you,” she explained. “It’s wild.” Taking my Nokia out of my Jane Norman bag, I paused to delete Lady_Sovereign – Love_Me_or _Hate_Me.mp3 to make space for the transfer.

As I sat there waiting for the technology to do its magic, I was naive to the fact that I was about to embark on my sexual awakening. That night, under my Groovy Chick covers, my face illuminated by the dim light of my flip phone, the strict constraints of my Ghanaian Christian background rattled as I devoured chapter after chapter. A proud bookworm, I’d never read something so salacious, so satisfying.

“Ricardo gt bhind me an held da sidez of ma bum firmly an slid his dick in an out of me. It felt soooooooo gud. He woz goin soo fast dat he woz tearin me out!! I moaned loudly, but afta a while i culdnt take it nemor.“

For so many of us Black Brits, the anonymous writer of Keisha The Sket – Jade LB – is as fundamental to the canon as Shakespeare or Dickens. Initially published on early social media site Piczo in 2005, the story follows the teenage escapades of the titular character. Keisha was “a girl from the ends, [who is] sharp, feisty, and ambitious; she’s been labelled ‘top sket’ but she’s making it work.”

Over a series of periodically updated chapters, we followed Keisha’s shenanigans as she navigated sex, mandem and the ends. All written in the most infamous of noughties text dialogue, lunchtimes and bus rides became far more colourful as the brave school kids amongst us read scandalous excerpts to a delighted, curious audience. The story jumped from person to person via our childhood Nokias to Motorola Razrs to Sony Ericssons, making it one of our first encounters with virality, earning notoriety as one of the most iconic pieces of literature in Black British youth culture.

In the years since its inception, the exact identity of Keisha The Sket’s author – our “literary foremother” has remained a secret. You could say she’s the Black woman’s Hannah Montana. When it was announced that Stormzy’s #MerkyBooks will be publishing the story in book form for the first time in October 2021, and nostalgic mystery began to spread amongst my peers. Just who is Jade LB? To what extent was the story autobiographical? Where is Keisha now? And most importantly, is she still a sket?

For me, the chance to meet Jade LB was a Rubicon Mango to the thirst of my 16-year-old curiosity. As I sat anticipating in the waiting room of our Zoom call, I imagined being face to face with a thirty something Keisha, complete with flaky, scraped back ponytail, Von Dutch hat and knock-off Juicy tracksuit. I envisioned her speaking in the infamous text speak manner of the story; I hoped she “wud lyk me” and share top tips on how to be “choong”.

Jade LB is not Keisha the Sket – but she has chosen to still keep her real identity under wraps, citing the protection of her wellbeing as a factor in her decision.

“Just who is Jade LB? To what extent was the story autobiographical? Where is Keisha now? And most importantly, is she still a sket?”

“If you’re a real original reader of Keisha, then you would know the site had my full government name,” she says. “People would hit me up on MSN or on the bus telling me they loved the story, people that I’m friendly with until this day. Then around 2010-ish, [using a pseudonym] became quite an intentional thing, definitely fuelled by shame and fear.” She charts the intense anxiety she felt as years passed and Keisha The Sket did not fade into the horizon, intermittently trending on Twitter and nostalgic conversations at house parties. Now, although no longer ashamed of her childhood creation, she works with young people and fears they may not be mature enough to process her as the author of such explicit content. If she does unveil herself to the world, she says she’ll go at her own pace. “Right now, I’m not ready,” she adds.

In the author’s note of her novel, Jade describes herself as a “strange observer” to the Keishas of her childhood. Whilst she believes she wrote the story objectively, she admits to grappling with Christian respectability politics and internalised misogynoir in the writing and aftermath of her initial literary debut. “I never ever re-read that thing,” she says of her own legendary saga.

Her new book is in three parts: contributing essays from cultural innovators, the original text and a new rewrite concluding Keisha’s story. “I had really built up a story in my head that it was just sex and nonsense. I had my cringe moments during the rewrite. Doing the rewritten story, really fleshing it out and piecing it back together, it was funny but I had my moments that were really dark, moments that were really emotional.”

In more recent years, after undergoing therapy and through the process of revisiting her childhood creation, Jade has come face-to-face with her fears and initial shame, embracing a healthier outlook on her own sexuality, Black womanhood and on Keisha The Sket. She now recognises and embraces the ingenuity of her work, acknowledging its cultural impact.

“I think it was popular because it depicted sex in text,” she explains. Reading it back there are some eyebrow-raising moments. Keisha recounts how one lover “started playin wit ma pussy lips [sic]”, and takes blow jobs a little too literally as she writes: “i took his warm dick an placed it in ma mouf. I started suckin an blowin on it, it drove him wild [sic].” With these nods to teenage horniness as well as naivety, Jade explains that it was one of the first times, with the exception of grime, that inner-city Black kids in the noughties were able to see the world they inhabited reflected back in a creative medium.

“It was one of the first times, with the exception of grime, that inner-city Black kids in the noughties were able to see the world they inhabited reflected back in a creative medium”

Returning to the text as an adult, she now realises that she was painting the often complex picture of heterosexual teenage gender dynamics – “the mandem” interacting with teen girls. She explains: “I write about how a young man’s energy sort of overpowers the teenage space. I think that we hear about this very negatively, as whiteness often is afraid of Black masculinity, but I hope I wrote it in a way that reflected that this was attractive to us. His loud clothes, the oversize coat in the house, Versace blue jeans filling up the whole space and answering of the burner phone, this was masculinity and manhood to us. I was recognising the hallmarks of our coming of age.”

The real Jade is a pleasant surprise. She is quiet yet quick-witted, academic and unapologetically proud about her Blackness and Caribbean heritage. When she talks about literature, her extensive knowledge and passion for books shines. This is reflective in her writing as despite being deeply inexperienced, teenage Jade managed to weave such an evocative tale.

She reveals that she used dramatic tales like those found in Jacqueline Wilson books as a blueprint. “At the time, she spoke to a lot of young girls with dysfunctional, unstable home situations and I really enjoyed that. My own upbringing wasn’t what I would call stable and functional.” Later, she would spend time in the library absorbing the sensuality of African American erotic novels, such as those written by the author Zane (who incidentally also wrote under a pseudonym), which would also inspire Keisha’s story.

“You only have to look at the new generation of Black TikTokers that set the tone and trends of the app to see how Black creativity is the lifeblood of new media”

Jade now has younger sisters in the throes of teenagehood; the advent of the internet and social media has meant the world is vastly different to the days 13-year-old Jade spent typing on her computer. Yet, similar to Jade’s own Piczo origins, Black teens continue to dominate and pioneer content creation on modern technology. You only have to look at the new generation of Black TikTokers that set the tone and trends of the app to see how Black creativity is the lifeblood of new media.

But what lessons has Jade learnt by being at the cutting edge of virality years ago that she wishes to instil in the upcoming generations of creative Black youth? “My little sister has been supported somewhat by me and people that have gone before her to understand how she can make the digital space work for her. Monetising her craft, for example,” she says. While there are many benefits to having a voice in the digital space, Jade is quick to highlight that it’s a double-edged sword. “There’s so many conversations to be had about safety including your emotional safety as well, when you consider that there are people in the space who are there to say or do horrible things.”

When asked whether she will gift her sisters the novel when it is released, she pauses thoughtfully. “I would want them to read it,” she replies slowly. “There is this idea of Blackness being synonymous with African Americanness. So I think that anything that champions anything that conveys Blackness, particularly in a historical or culturally specific context is powerful, and something that people should be very much engaged with.”

“I think that anything that champions anything that conveys Blackness, particularly in a historical or culturally specific context is powerful, and something that people should be very much engaged with”

Jade LB

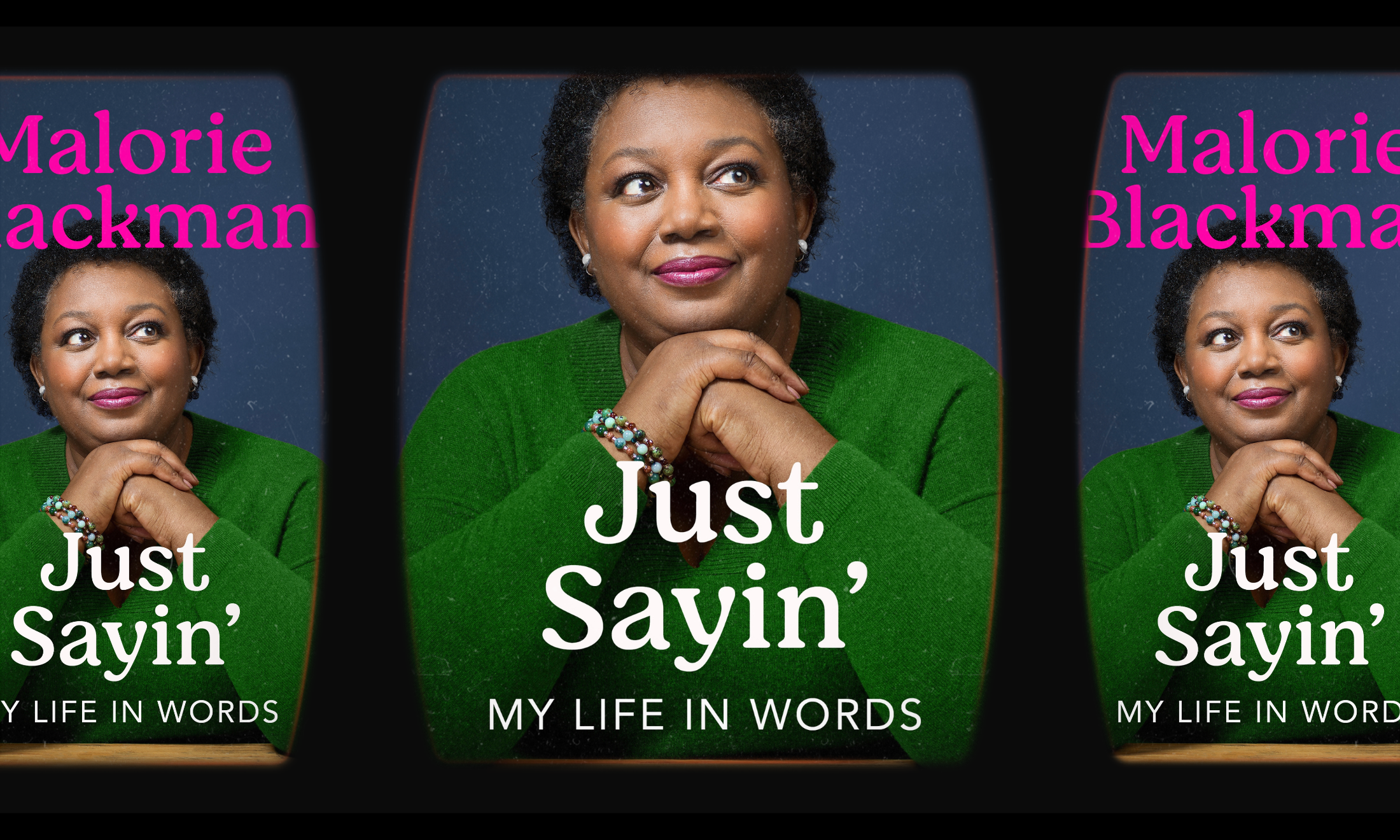

The #Merky project is rooted in a celebration of Black British stories and storytellers. Wordsmiths like Aniefiok Ekpoudom, ‘Peng Black Girls’ rapper ENNY, Queenie author Candice Carty-Williams and poet Caleb Femi. “I wanted writers who we would look back at and say they wrote, for, to or about us as a people. The contributors are at the helm of literature, poetry and cultural commentary. The theme of the contributing essays was to pay homage to this DIY culture and the way we are archiving our experiences.”

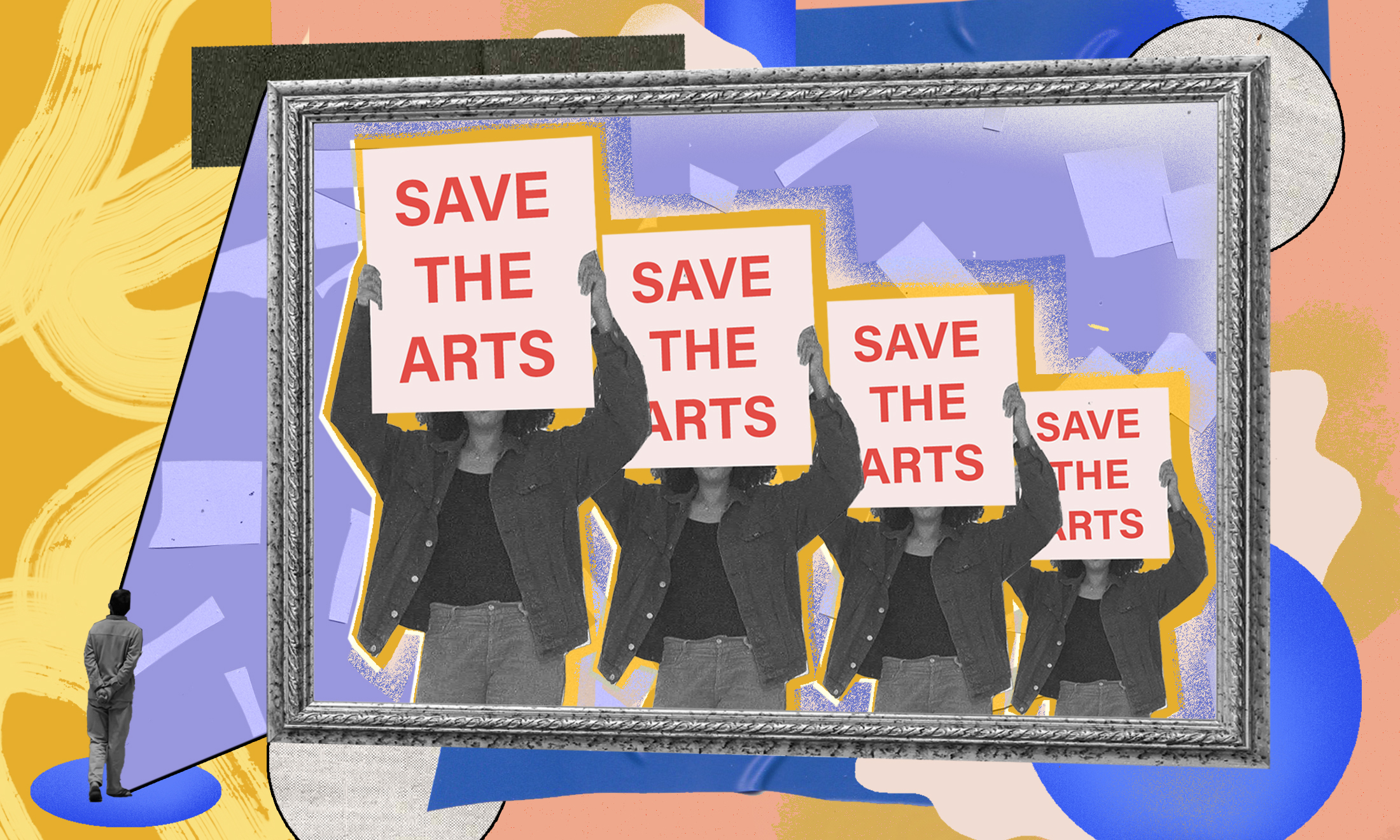

Now, Jade states, she is comfortable with the title of “writer”. “If I had no interest in writing we could simply republish maybe some commas on the original text. But for me, there are still conversations to be had about how literature is seen traditionally. Why doesn’t the original text, in text speak, deserve to be in book form when it is the text format that garnered the attention? That’s why we are here today.”

There is an undeniable grassroots power in the initial mode of distribution of the story; it represents a disruption of the canon in its very essence through its language and dissemination. “I didn’t intend to decolonise literature – but now we’re here,” Jade laughs.

The topic of decoloniality and democratisation is a motif throughout our conversation. I cannot help but wonder how she felt navigating the still incredibly white world of publishing. According to the Diversity Baseline Survey conducted by Lee & Low Books, 79% of those who work in the industry are white. We laugh as we talk about the word “sket”.

“It is so funny because I’ve picked up in conversations that for the publishing industry – having ‘sket’ on the cover of a book is a big thing,” says Jade. “But for me, it is like, why? It is just a word, innit? There are so many words that get people’s backs up, but it is expression, it is what we came of age with. There’s also the cultural element, my mum is from Trinidad and she blows the “c-word” like it is nothing – it doesn’t hold the same weight as it might for other people.”

“In the book, I wrote my own solemn conclusion to Keisha’s story that suggests what happens: life starts”

Jade LB

“There are more decolonising conversations to be had, even about resources and advances and what can we do to support people? As Kanye West says, “pain is expensive – the emotional journey that I’ve been on with this, I have realised there are so many people with stories, but it is expensive delving into that pain, you know?”

As my time with Jade was coming to a close, I had one last burning question. Nearly two decades after we first met her, with the original audience firmly into adulthood, where is Keisha now?

“It is interesting because going back to this conversation about democratisation, people started to write their own endings to Keisha’s story – through the grapevine I’ve heard these fantastical endings,” Jade explains. “In the book, I wrote my own solemn conclusion to Keisha’s story that suggests what happens: life starts. We learn to suppress whatever pain that led us to run riot on the street. We look back to the Malachis or Ricardos or Keishas we grew up with – then life starts, they have a child, have to get a job or someone dies. But life just starts.

This article is featured in gal-dem‘s 2021 print magazine, The Roaring Twenties. Find out more here!