Hayfaa Chalabi

Against the binary: Feeling whole in divided Cyprus

Despite fearing and doubting the border, it’s actually one of the reasons I relate most to my homeland.

Yas Necati and Editors

29 Oct 2021

Welcome back to gal-dem’s monthly gender column ‘Against the binary’, bringing you Yas Necati’s latest reflections on finding gentleness, home and joy as a trans person.

There’s a beach near my village in Cyprus, right on the border, where the sand stretches for miles and you won’t see a single other person all day. When I was younger, I loved to wander down the coast exploring the rock pools, finding crabs and cleaner shrimp. We called this beach kumlu deniz – translated to “sandy sea”. Before I went off exploring, my mum used to warn me not to go too far or I’d be “on their side”. Except nobody was really sure which direction that was. Until recently, the beach went up to a military-controlled area where you can still see craters in the rock face from weapons testing. It is also the place I associate most with the word “home”.

I have often wondered about what it means to associate home with a place of conflict. In 1963, my grandparents left their home in Cyprus, three years after the British were thrown out of the island. My grandmother still cooks with olive oil from the village, still adds a teaspoon of rosewater to every cake she bakes and still wants the taste of her homeland in all of the food she eats.

Before last week, I hadn’t been to Cyprus, and in turn to kumlu deniz, in seven years. The last time I went was just after my grandfather died, when I was 18. And despite wanting to go back many times since, I had been too nervous. My grandparents’ village is small and remote.

When I was 18 my gender nonconformity could be passed off as me being an “experimental teenager”. But what would it mean to return to my homeland as a very openly genderqueer adult?

“What would it mean to return to my homeland as a very openly genderqueer adult?”

This time round, I was visiting with my partner and my family was worried about our safety as queer people. But I wasn’t worried – at least, not any more worried than I am generally as a queer and trans person. I was much more concerned about social rejection – it would hurt so much more to be rejected in the place I called home. I associate Cyprus with belonging, and I was scared about that being shattered – it would have really shaken my sense of self.

There’s even a recently-started Cypriot diaspora queer group in London that I’m too shy to go to. It feels too monumental to be in that space, I both crave it more than anything else and fear it because I’m scared it won’t be what I crave.

Homegoing is scary. At Heathrow airport, I held my partner’s hand tight and I said to them, “Whatever happens on this journey, it will change my life”.

Cyprus is a tiny island. In the short journey between Istanbul airport and Ercan airport (the sole airport in the North, reachable only via Turkey) you can literally see the outline of the island beneath you. The burun (nose) stretches out like a sword, or a hand. We touched down early in the morning and our first steps were unfortunately on airport tarmac rather than the lush green of the countryside. But even in the plane parking lot, I could feel the things that I associate with Cyprus – the air that tastes sweet on your tongue, the sun like a gentle embrace on your skin, the skylight and bright and still, as if in meditation.

“I wasn’t expecting to see so many queers, and with each encounter, I felt closer to my homeland”

All the worrying about being non-binary very quickly dissipated when we were met outside by a good friend of my grandmother’s, and her grandchild, who had an undercut and big queer energy. They dropped us off in the capital and we were warmly welcomed there too. We bumped into a trans woman and had drinks with her that evening – she shared tips with us about all the queer nightlife spots we could check out in Girne/Kyrenia, another major city. We went to the bandabulya (covered bazaar) and in a shop that I remembered from my childhood, full of Turkish delight, there was a queer behind the counter. Another woman in a small café flirted casually with my partner. It seemed we were bumping into more queers than in London – or at least it felt that people were more in solidarity here, all of us making ourselves known to each other.

I wasn’t expecting to see so many queers, and with each encounter, I felt closer to my homeland. I had always known it held us too, but I had never seen it with my eyes. Now here we were. It felt comfy and safe and like a really deep exhale.

Next came the village. As my grandmother’s friend took us through those mountains, crappy Turkish pop music blasting on the car radio, her son smoking with the window sometimes rolled down, the sea on one side of us and the land silver with sun on the other, I felt tears meet my cheeks. The town at the bottom of the mountain was a long lost relative, nodding us through. As we wound up and over, back into the valley on the other side, I wasn’t worried anymore. And we had no reason to be – we were driven straight to an uncle and aunt’s home, where they had made us vegetarian food especially. Over the few days we stayed in that village, we were visited countless times by cousins, aunts, uncles, relatives from all over. They fixed our gas and made us stuffed courgette flowers. They gave us olive oil and took us on tours of banana fields. We were welcomed like family, both of us.

“The land is not binary, and yet we have tried to split it into two separate halves”

On the night we left Cyprus, I wrote in my diary, “If I have to get on a plane here, I want it to be the place I holiday from, not to.”

Cyprus’ capital, Nicosia/Lefkoşa/Lefkosia, is currently the world’s only divided capital city. On this trip we did something life-changing, and we crossed the border. We handed our passports and proof of Covid-19 vaccination to a Turkish soldier, then walked a few metres through the UN-controlled buffer zone and handed the same documents to a Greek soldier, who waved us through. In the buffer zone there was graffiti on the wall – “one Cyprus”.

Crossing the border felt easy. Despite fearing and doubting the border, it is actually one of the reasons I relate most to Cyprus. The land is not binary, and yet we have tried to split it into two separate halves. It’s a real shame that humans have done this. Gender is also not binary, but again we try to divide it into two. When I crossed the border in Cyprus, it felt familiar. Even though I had never crossed that particular border before, I have never felt comfortable on just one side of a binary.

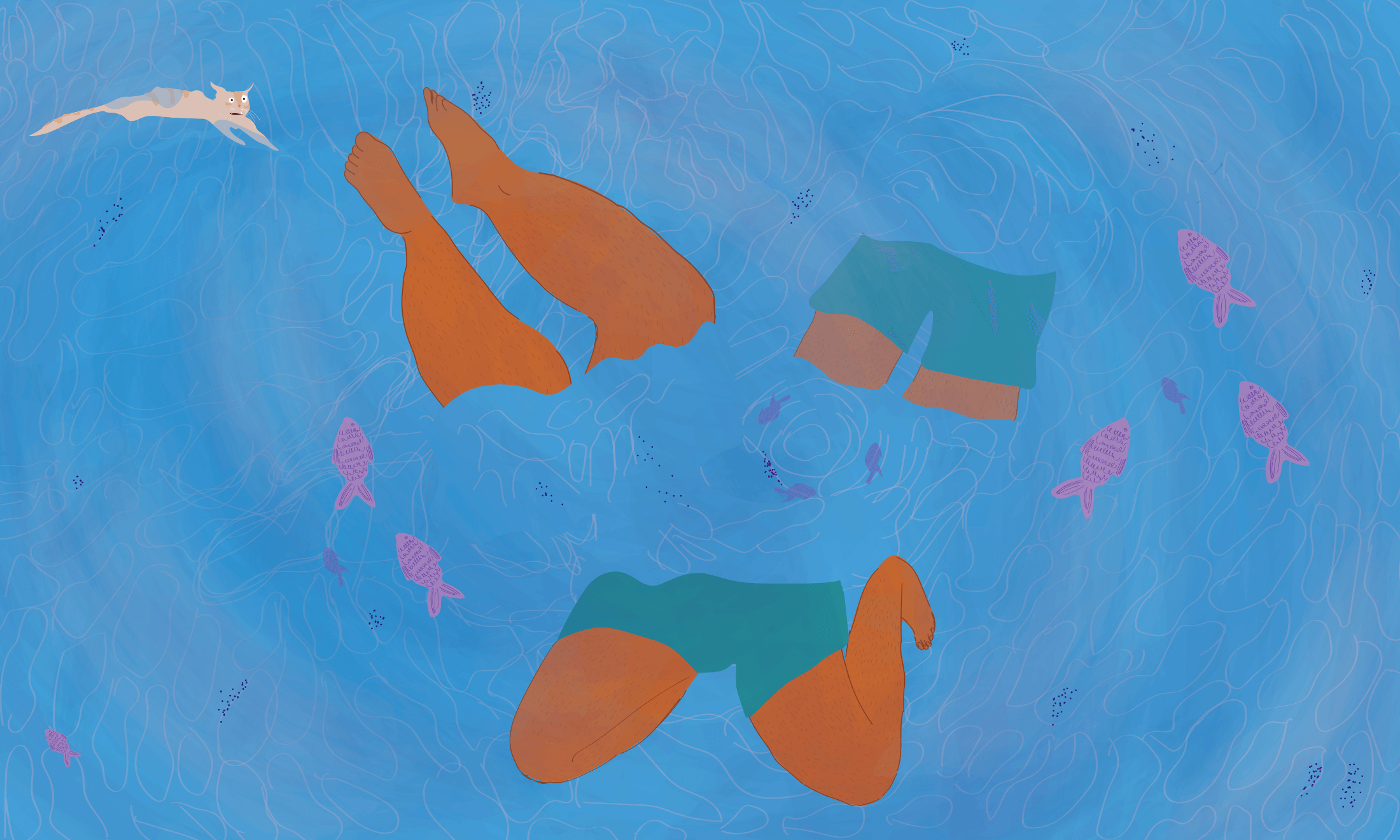

Which takes me back to the beach and its rock pools – also on the border, but a point much less closely guarded by the military. Crabs, fish, shrimp and ants made their way freely over the land, unbothered by human division. When we were on that beach, we were in an ambiguous and unclearly defined territory. We were on one half, both or neither. It was home – a joining and separating point – and I will always keep trying to go back there.