Against the binary: Reconnecting to Islam as a trans person

I haven’t returned to a mosque since I was a child, but I’m sitting with prayer in other ways.

Yas Necati

02 Dec 2022

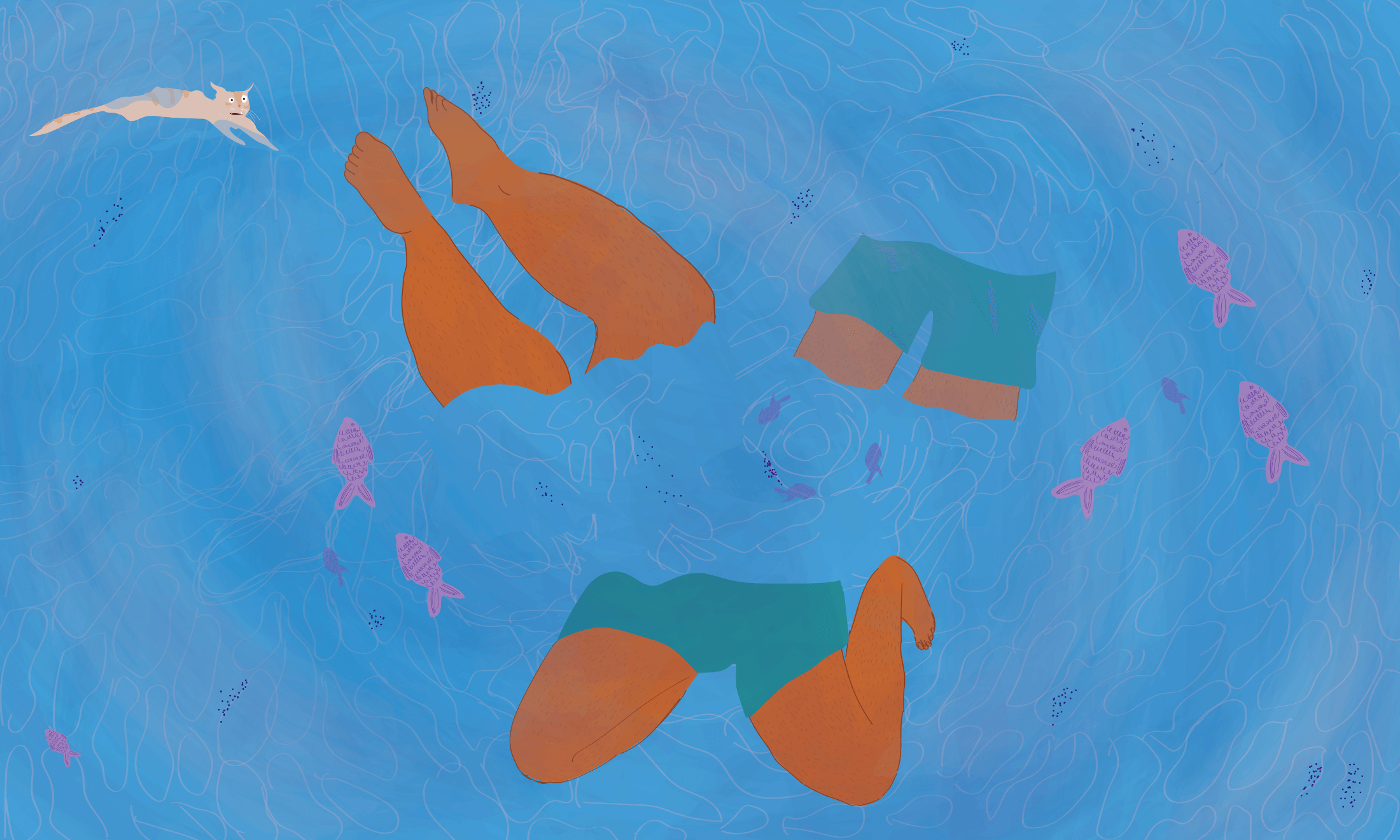

Hayfaa Chalabi

Content warning: this article contains mention of suicide.

I haven’t entered a mosque since I was a child. Not even a teenager, but like, a proper kid. I wouldn’t know which side to enter, and just like how mosques have sides, so too does Cyprus. Unlike both of these places from my childhood, I’m terrible at binaries, so I’m struggling to return.

Logically, I know I don’t need to enter a mosque to practice Islam, but that doesn’t stop me from yearning for it. When the Hoca (Imam) calls for prayer in the Cypriot village I’m from, I feel like a firefly, all glowing under my skin. I want to follow that call; I want to sit with others in silence and in song; I want to feel held and connected and part of something bigger. But there is no door for me.

There is no entry way for me into our buildings, and no space for me to sit on our floors. So I haven’t been back to a mosque.I’ve forgotten some of the prayers I used to know and a feeling that was once familiar.

“When the Hoca (Imam) calls for prayer in the Cypriot village I’m from, I feel like a firefly, all glowing under my skin”

As a kid and teenager in London, I lived a few minutes walk from a mosque, and sometimes I would climb a tree on the other side of the fence and sit there for a while, listening as hard as I could. When I left London, I moved to a place with no mosque. We have a local online queer group where I’ve occasionally, hopefully, made call outs to other LGBTQIA+ Muslims but no one’s ever replied. I don’t know any other Muslims here, queer or otherwise. My connection to faith was mostly through my grandmother, but now that I live far from her, I have to learn how to celebrate Bayram (Eid) and sit with prayer on my own terms.

I’ve never been very religious, and neither have most of my family. It’s something that we are connected to ritualistically and culturally, used to help us stand up in times of great change: births, deaths, marriages. When my grandfather died a few years ago, we held a Mevlit in my other grandparents’ home. All the women, and I, sat in one room grieving and praying. The men sat in the other, drinking coffee and socialising. The words of prayer travelled through my body like a murmuration. I cried and the words felt clumsy on my lips, but it was beautiful to sing and mourn with the elders of my community. Even the worst vocalist sounds beautiful in prayer.

“I want to feel held and connected and part of something bigger. But there is no door for me”

The hums of that room often enter my bones and stay with me for a while. They were there when I lost two trans community members to suicide, one last year and one the year before that. They were there when I jogged through the loss; they’re there when I’m misgendered and there as I’ve tried to build a new home. And here I am, finding faith in brunches and drag nights, in jumping in rivers, in walking in the mountains and trying to see the sea, in the ritual of starting the fire each evening, in holding friends’ hands.

I hosted my first Bayram in this community, and though nobody is Muslim, they came. I might not be able to enter the mosque, but I can still cook the dishes I ate there; and I might not be able to sit on those floors, but the forest floor that changes with the seasons is all the prayer mat I need. And although I might not be able to listen to the Hoca’s prayer right up close, I can always find that call inside me when I’m transitioning. I can learn words and rhythms for myself.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.