Hostile

How a new documentary explores the UK’s hostile environment through the eyes of those impacted

‘Hostile’ director Sonita Gale’s debut film follows Black and Asian migrants as they take on the immigration system.

Jeevan Ravindran

20 Jan 2022

Right now, the UK government is pushing ahead with its most comprehensive attempt to essentially close the country’s borders to those who can’t afford to pay their way in. An already horribly hostile environment is about to get that much more aggressive. Which makes it a bleakly relevant time for the release of a new documentary from British Indian filmmaker Sonita Gale that examines the diverse experiences of certain migrant communities at the sharp end of the policy.

Hostile is Gale’s debut film. Told through the eyes of Black and Asian migrants and the advocates supporting them, the documentary unpacks just how multifaceted and damaging UK immigration legislation can be. Featured characters include NHS worker Farrukh Sair, whose sons don’t have British citizenship despite being born in the UK. Windrush Scandal survivor Anthony Bryan recounts his struggles against deportation to Jamaica. And community organisers Daksha Varsani and Paresh Jethwa open up about their work running a community response kitchen in Brent during the pandemic, helping destitute students who were kicked out of their universities.

Forty-six year-old Gale grew up in a working-class migrant family in Wolverhampton and was inspired by her own parents’ experiences of Partition. Although she’s been producing films and documentaries for years, it was the pandemic that made her decide to direct her own film.

“Told through the eyes of Black and Asian migrants and the advocates supporting them, the documentary unpacks just how multifaceted and damaging UK immigration legislation can be”

Although she first set out to document migrant communities’ response to the pandemic, she was drawn to the hostile environment through the individuals she reached out to. The switch to filmmaking has already paid off for Gale, as Hostile has been long-listed for the BAFTA Award for Outstanding Debut by a British Writer, Director or Producer.

gal-dem sat down with Gale to talk about the filmmaking process, the stories she uncovered about the deep-seated roots of the hostile environment and her journey as a first-time filmmaker impacted by her own migrant background.

gal-dem: I’m also from a migrant background. For those who don’t directly face these legal issues themselves, it can be hard to understand nuances of how difficult the system is to navigate. Did you find that that was the case?

Sonita Gale: Well, firstly, I grew up with a mum that couldn’t speak English, and she couldn’t write English. She lost her husband at the age of 49 and had ten children. As a child, I saw my mum struggle with filling in applications, going to the bank, having the insurance man come over Friday nights, whilst at the same time her working a six-day week in a factory. So I know what it’s like to have a parent that can’t speak English, and can’t read and write English.

Growing up around that environment allowed me as a filmmaker to have that deep level of empathy and understanding, and be able to go into those environments with a sense of ‘I understand why this is happening. And I understand why you’re going through this.’ I wanted to spend a lot of care and attention and really think about how I could film that without making it about me, or putting my own opinion on it — and making it about them and giving them the opportunity to tell their story.

Everyone in this film had a voice. I was just a medium to let that happen. The emotional bit is very interesting. Because I come from a background where my parents were Indians and came from India and fled Partition and its aftermath, I felt like everyone I was filming was a brother, was a sister, was a cousin, was a parent. It felt so close to my community where I grew up, in Wolverhampton. So that familiarity just allowed me as a filmmaker to have that authenticity and that level of empathy, like I said, that I think it needed for this film. It really did.

One of the major historical events referenced and explored in the film is Partition. And how difficult was that for you to explore?

Yeah, that was very difficult. As a child, my mum would tell me stories about her harrowing experiences. I actually recorded her on dictaphone for a while, speaking about Partition. She would often say to me, you know, “puthar, it was hard, it was so hard, and I would never want you to experience what I went through. But life was so tough, it was unbearable”. She would weep, she would cry.

The contemporary hostility we have in our country doesn’t come just from Theresa May in 2012. It doesn’t just come from the New Labour movement in 1999. It goes back further than that. And I went back to legislation and policies from the 1960s and 1970s and 1980s. And then it started making me think about empire, and empire took me to Partition.

So Partition was deeply important because of my mother’s first hand experience as a child. I also wanted to do it for our South Asian community whose parents experienced this, and whose ancestors experienced this.

When I was watching the film, I got this real sense of anger that builds throughout, especially in the little moments. For example, community organiser Paresh says “shame on the government” as he tears down British flags hanging in the community kitchen, after the council fails to support their project.

That scene for me represented a juxtaposition, of the flags being there and these migrants feeling proud of being British, yet Britain tries to push them out. Where did that growing anger come from?

Whilst I was filming, there was an explosion in this world. We have a pandemic, George Floyd dies, the Black Lives Matter protests come to the forefront. And I think at that moment, people just felt that they’d had enough — the NHS workers were not getting their pay rise, NHS workers, mainly migrant workers, were dying. It was a moment in history where people were very upset and angry. And I was capturing those protests whilst filming the progression of the story and the lives of my participants. It was a moment in history during those 18 months that I needed to put them in the film.

The more I filmed, and the more I learned, the more angry I was getting. Not outwardly, but inwardly. About halfway through my filming, I think it was maybe like June, July, I was thinking, ‘Something’s coming. And it’s going to take us all and it’s going to be big.’ It feels like this is a testing ground, it feels like the hostile environment has been put in place to target migrants — who’s next?

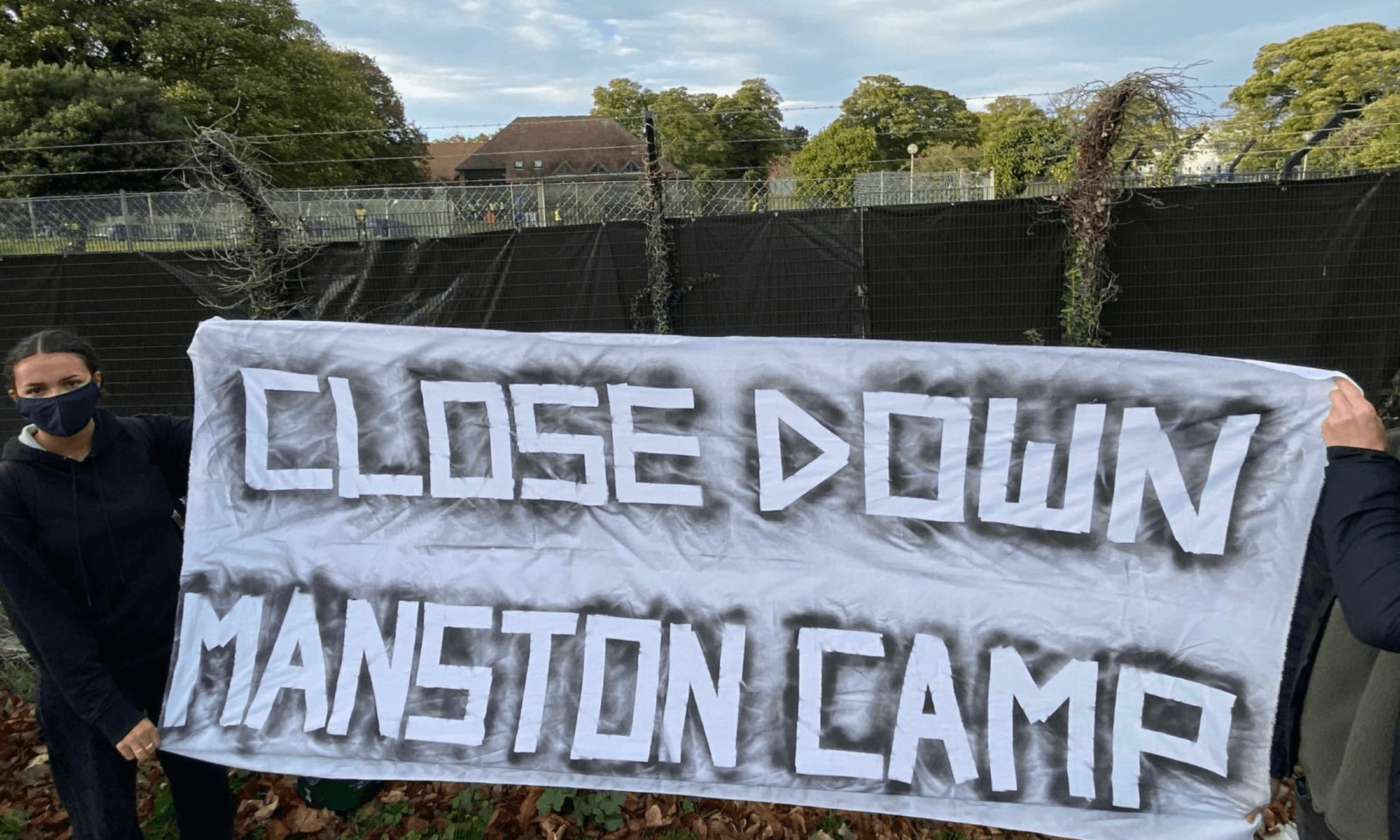

With the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, we see the government turning on Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities, and reducing our rights to protest. The hostility is building and building and building. We finished Hostile in September, and these things are continuing to happen. [We’re] on our way to an autocratic fascist state. So you’re right, it was a very emotionally charged film, because at that time, there was a huge amount of emotion and uproar and anger. And there continues to be so, very much so.

You said you didn’t even know what NRPF (No Recourse to Public Funds) was before you started the film. And there were all these other elements that you were just learning about along the way. Does that make you then reflect on how secretive all this policy is?

Absolutely. In fact, everybody I met outside my participants and the people I met that were struggling from NRPF, didn’t know what NRPF was. Nobody knew what it was. The hostile environment is hostile for many reasons. But one big part of the hostility is that the legislation and policy is very difficult to understand. Even as an English-speaking, British-born citizen, I couldn’t understand half of the paperwork.the applications are extremely lengthy, the narrative around it is extremely wordy. And it’s that for a reason, because it tries to catch you out, it tries to make it difficult for you to understand what you’re in for.

You can apply for exemption from NRPF, but you have to go through about six to eight months of application filling, then somebody has to tell you whether you are exempt and then you have to prove that you’re destitute. You can see how troubling it is and frustrating it is. Seeing how that was affecting people, I realised that there is a reason why it’s completely stealth. It’s there to make life so unbearable for you that you either leave voluntarily, or you’re so broke that you get kicked out and you get deported. Or you hear about it, and you just don’t want to come to this country.

We see that in the film, like when Farrukh says his children were born here, but they don’t have British citizenship. What was it like seeing those moments unfold?

How can his children be born here, yet not have British citizenship and be on limited leave to remain and have to be in the same system as Farruk where they have to renew their visas every two and a half years? They have to pay an NHS surcharge [an annual fee for the majority of migrants to allow them use of the NHS]. And they are subject to NRPF. And it’s like Farruk says, how can they pay for their Pampers? Everything is on him. He has to work all the time, whilst incurring these significant costs for application. So that’s why he’s in significant debt. Watching all of that unfold was terrible.

And finally, who’s the target audience for this film?

I think it’s good to approach the audiences that aren’t necessarily aware of what’s happening. Really, this film affects so many different generations; look at the students queuing at food banks. My son is 16. I cried filming those [international] students [with no recourse to public funds], because I would look at them and think, ‘how is this even happening?’ These children, like, their parents don’t even know. And, you know, I’d buy them a cup of tea and think, they haven’t got money on their phone, they haven’t got anything to eat.

There’s a wide range of participants in the film. That wasn’t deliberate – it was indicative that a wide range of people are being affected by the hostile environment. I’m hoping that because of that it will tap into a wide audience; [perhaps] younger audiences will be [particularly] affected by the students’ story, while older audiences will be looking at Anthony and thinking, ‘how does a man that’s been here for 50 years get deported?’

I think my ideal audience though would be the demographic that wouldn’t necessarily go and see a film like this, or are not directly affected by this, or don’t know anyone that’s directly affected by this. Audiences that would not necessarily have empathy for the participants that are in our film, and might have an alternative view about the participants in our film – the view that was used for the Brexit campaign, the view that’s been used by our current government to drive a wedge between people in our society.

And that’s why divide and rule was such a main theme of my film, to actually say, well, look, there’s a lot more that binds us than separates us, right? So I want to merge communities by going to those communities where I’m going to be faced with questions. And I will answer those questions. And they will see that there’s more that brings us together that sets us apart. So that’s my aim with the film, is to build those bridges, and to start dialogue about that, and about our similarities and our differences, that’s really what I want to do as a filmmaker.

Hostile is now in cinemas across the UK until March; several screenings will be followed by Q&A discussions with Gale and others. Get tickets here.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?