Tim Tebow Foundation/Unsplash

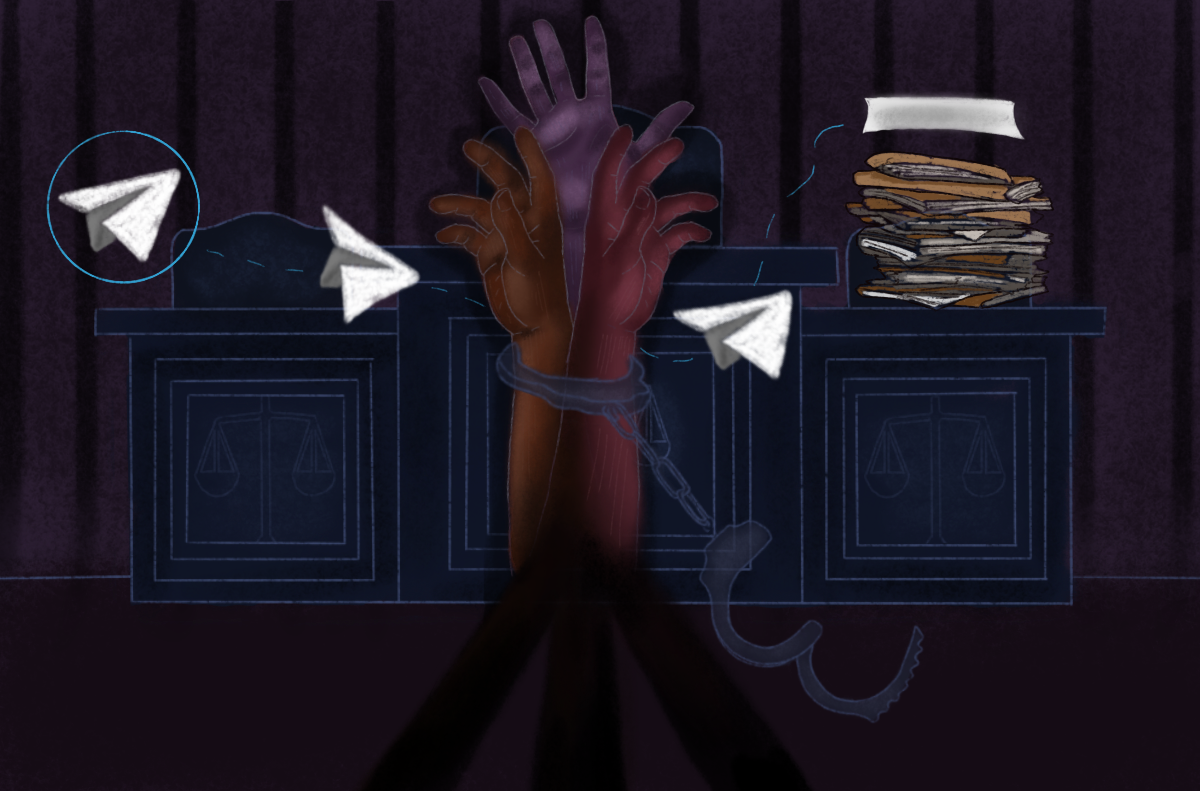

‘I can physically feel the weight on my shoulders’: life in Britain’s hostile environment

For years the government has been pursing racist immigration policies that have pushed the most vulnerable to the margins. Some of those affected tell gal-dem what it means to live at the mercy of the Home Office.

Naomi Larsson Piñeda

29 Jun 2022

Content warning: this article contains mention of domestic violence and suicide

Desiré* was applying for university when she first discovered she was undocumented. At 18, Desiré had lived and attended school in the UK for seven years, never questioning or doubting her settled status in the country she called home. It was only when the UCAS form required information on whether the applicant would pay international or national fees that her mother revealed her immigration status.

“It was painful, having to face those challenges and still be young; I was heartbroken,” the 33-year-old says, recalling the discovery 15 years ago. It was like “the curtains had been drawn”. She remembers not being able to go on school trips abroad but believing the reason was to do with financial constraints – she never thought the reality was that she didn’t have legal rights to live in the UK. “It broke me really, it just brought the past back,” she tells gal-dem.

Desiré believes her mother, who she moved over with from Nigeria in 2000, didn’t tell her in order to protect her from Britain’s hostility towards migrants.

Since the age of 19, she’s been trying to apply for leave to remain (settled status which gives the right to live, work, study and apply for benefits in the UK) but, like the thousands of others who have uncertain immigration status here, she lives in limbo at the mercy of the Home Office.

“Sometimes I feel like I can physically feel the weight on my shoulder. But you have to be strong, because it could lead to unspeakable things,” Desiré says.

For years, the government has been pursuing policies to make it almost impossible for migrants and the children of migrants – particularly people of colour – to live in the UK. The latest of which was followed through on 28 June, as the rest of the Nationality and Borders Bill came into force. Viewed as a blatant attack on asylum seekers, it will also broaden powers to strip legal status with a disproportionate impact on marginalised communities.

“The changes we are seeing are underpinned by racism”

Bethan Lant

An analysis of Home Office legislation released in May 2022 found post-war immigration laws were rooted in racism specifically designed to reduce the number of people of colour allowed to live and work in the UK. This discriminatory history holds the origins of the Windrush scandal and laid the foundation for a decade of hostile environment policies pursued by the Conservative government.

“Within the sector there’s always been absolute understanding that the changes we are seeing are underpinned by racism, discrimination,” says Bethan Lant, training, development and advocacy manager at Praxis, a charity for migrants and refugees. “But there’s always been huge denial on the part of the Home Office, and it’s often hard to discern actual intent – deliberate malice – from complete incompetence.”

Ten years ago, then-home secretary Theresa May gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph where she bluntly set out the government’s aim: to make Britain “a really hostile environment for illegal migration”. From then, private landlords, employers and NHS staff would be encouraged to carry out checks on migrants to ensure their legal status. The same year, the government increased the length of time from 14 to 20 years that someone without legal status has to have been living in the UK before they become eligible for indefinite leave to remain, which then requires another 10 years with renewals every two and a half years at a cost of an average £2,600.

For years prior to this, the government had implemented a raft of changes within the immigration system. There were huge cuts to legal aid for migrants, apart from asylum seekers or people who were trafficked, for example, but May’s statement was “the first time it was crystallised that this was not a series of things going on, it was a policy movement,” Bethan says.

“Theresa May’s language was very much pointed towards ‘undocumented migrants’, ‘illegal immigrants’ as she would she would put it, but we were already seeing the evidence that the impacts were much, much wider,” she adds. “We were seeing the seeds of what would turn into Windrush, we were already seeing people locked out of the system because they couldn’t get immigration advice, or legal aid for the application fees.”

The insidious nature of immigration system has affected the lives of hundreds of thousands of people being forced to live without legal permission in this country. The reasons are varied and complicated – laws have changed, some are unable to prove legitimate asylum claims, documents have been lost – but the consequences are clear. Unable to access legal aid, free medical treatment, housing, jobs or open bank accounts, the already vulnerable are pushed even further to the margins.

“It makes you feel you’re not human, like you’re not deserving of what everyone around you has”

Desiré

Desiré has given up her dreams of becoming an architect as the years have passed and says the system has put her life “on standstill”. “There are so many things I’m missing out on that I should be able to do – get a job, travel. It makes you feel you’re not human, like you’re not deserving of what everyone around you has. It’s horrible,” she says.

“They’ve created a wall, and with the policies they keep bringing yearly it just makes it harder to go over [the wall].”

Melanie*, a singer/songwriter from Jamaica, has been living in the UK for 21 years and is currently in the process of the 10-year route to leave to remain. While she reapplies every two and a half years, she’s unable to travel which has put planned tours into question. She says she’s lost a lot of her positive air, “the thing that made me want to be an artist in the first place – the people person that I am, my happy go lucky [nature].”

She has a “lot of bad memories” about her experience of the hostile environment, and is furious at the injustice. “My grandmother is a British citizen – she used to live here. My mother comes from a commonwealth country, they should automatically be British citizens,” she says. “I want to cry. I’m very strong, but my children don’t know.”

“The hostile environment doesn’t let you breathe,” says Dimple*, who arrived in the UK from India 14 years ago on a visitor visa when she was just 23. She is a survivor of domestic abuse, and recalls her former partner inciting fear into her that she couldn’t call the police because she didn’t have legal status. It was not an unfounded threat; thousands of victims of abuse have been referred to the Home Office for possible deportation after reporting crimes to the police. An investigation by the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants found police had referred 2,656 victims of crime to immigration enforcement since May 2020.

“The hostile environment doesn’t let you breathe”

Dimple

“I was very badly in depression,” she says, describing her suicidal thoughts. “I thought, if I’m going to [commit] suicide, then my daughter can stay in this country.”

Dimple had sold gold jewellery and any items to pay the thousands of pounds required in solicitor and Home Office fees, but authorities initially rejected her application for leave to remain for her and her two-year-old daughter (the UK scrapped birthright citizenship in 1981). Without settled legal status she was unable to access the vital legal or health support she needed. With no other option but to escape the abuse at home, she left her partner and became homeless, spending one night on the street with her daughter.

After being referred to a social worker, they were moved to unsuitable and dangerous temporary accommodation. “The room they gave me had blood everywhere. My daughter didn’t know and she started licking the human blood. I saw a red colour on her hand. I was scared to go out of the room, I was scared for my daughter too.”

After months of insecurity she was referred to Praxis’ immigration services, and in 2020 secured the 10-year route to leave to remain. The experience has been unimaginably traumatic, and she was diagnosed with PTSD.

“Now I feel ok sometimes, but I can’t sleep for more than two or three hours. But today when I dropped my daughter at school and I saw her face, she’s very happy. I try to help her get a good life.”

The weight of the experience remains as people without settled status are constantly reminded of the state’s efforts to further subjugate them. It took the European Court of Human Rights to halt a deportation flight to Rwanda, the first scheduled flight in home secretary Priti Patel’s plans to cut down on ‘illegal immigration’.

“The hostile environment isn’t about undocumented migrants, it’s about anyone who is a migrant, but also who happens to be the wrong colour, have the wrong name, have the wrong accent,” says Bethan.

“We have a system whereby people are much more likely to get stopped and discriminated against because of the colour of their skin, or because of where they were born, regardless of their immigration status.”

*Names have been changed to protect anonymity

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?