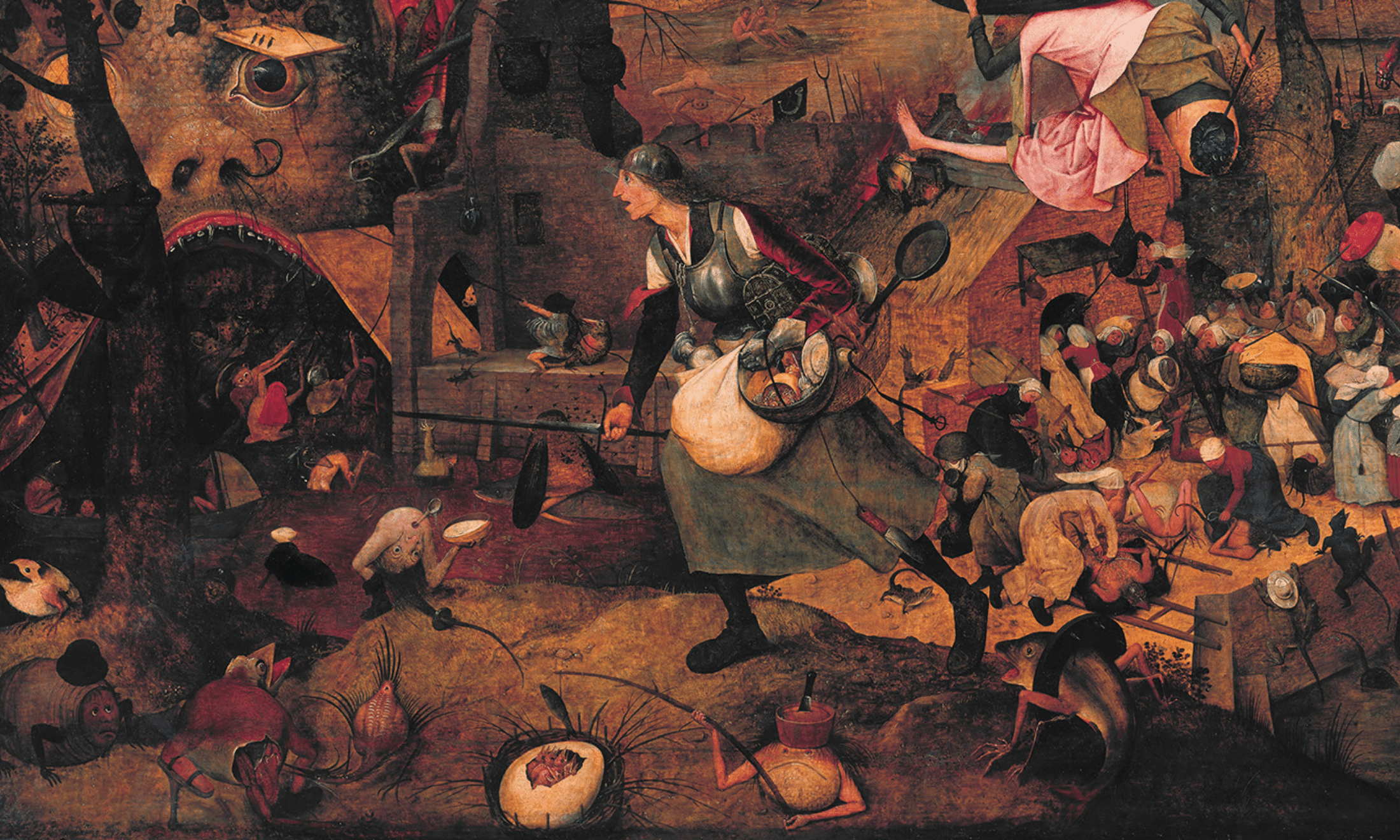

Pieter Brueghel via Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

How apocalypse stories have helped to soothe my anxiety

Strangely, my problems have become more manageable when placed in the context of apocalyptic desire.

Katie Goh

29 Jan 2022

Ten years ago, the world ended. It was 2012, and a (mis)interpretation of an ancient Mayan calendar prophesied that the apocalypse would arrive on 21 December 2012. Depending on your doomsayer, this particular apocalypse was heralded as either a mythical planet colliding with Earth, a reverse in the Earth’s rotation or a supernova cracking open above us in space. People panicked, Hollywood studio executives cashed in on public fear (who could forget the movie 2012 starring John Cusack, released in 2009), and anxious netizens, like my teenage self, started frantically researching whether the world could actually end on 21 December 2012.

As that date approached, I found myself caught between scoffing at the idea that the apocalypse could be speculated into existence by conspiracy theorists and embracing the possibility that I wouldn’t make it to my twenties. I didn’t actually believe that the world would end, but as an overly anxious teenager, I loved the calm nihilism a fictional apocalyptic scenario invoked in me. “Why worry about getting high enough marks to get into university when the world could be ending?” I asked myself. “Why should I stay up at night overthinking something I said at a party when we might not make it to 2013?” There was something perversely soothing about leaning into the possibility of total annihilation. My problems became smaller in the face of such a high-stakes disaster; my anxiety became strangely more manageable when placed in the context of this apocalyptic desire.

“I didn’t actually believe that the world would end, but as an overly anxious teenager, I loved the calm nihilism a fictional apocalyptic scenario invoked in me”

Obviously, the world didn’t end nearly a decade ago, but 2012 – and the many, many other times people have predicted the apocalypse – points to a recurring cultural fascination with humanity’s imminent demise, one that is as old as Noah’s Ark and as contemporary as the popularity of Station Eleven. And lately, as looming disasters – which are far more real than 2012’s Mayan calendar reading (see: the climate crisis, economic instability, the Covid-19 pandemic) – take precedence in most of our minds, I’ve found myself returning to fictional apocalyptic stories to soothe my anxieties once more.

Rather than turning away from the fear of catastrophe, reading books, playing games and watching movies about people trying to survive the end of the world made me face my apocalyptic mindset. It didn’t cure my mental health on its own, but it did give me the tools to begin making sense of the despair I felt was surging towards me, like a metaphorical and literal incoming asteroid.

It might seem strange that our species, which has scraped through plenty of real man-made and natural disasters over the centuries, is so fascinated with our collective death that we turn to fiction to hypothesise about the end of days. But stories have an incredible malleability to focus our minds, and people have always turned to imagined catastrophes to tell stories of what it means to be human because disaster, whether real or fictional, has always bound our species together, illuminating the best and worst of us.

“It didn’t cure my mental health on its own, but it did give me the tools to begin making sense of the despair I felt was surging towards me”

Although fictional apocalyptic scenarios have always existed – from H. G. Wells’ tale of colonial guilt, the late 19th century novel The War of the Worlds, to Hollywood’s modern “cli-fi” movies, like 2004’s The Day After Tomorrow, to Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 pandemic movie, Contagion – when I was a teenager in the 2000s, their popularity exploded. Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games trilogy became bestsellers – published as masses of protestors took to the streets to campaign for more just economic and political systems – while the number of zombie movies released in the 2000s has almost quadrupled in comparison to the 1990s.

Their rise in popularity at the turn of the millennium is hardly a coincidence. The 2000s have been plagued by a feeling that the apocalypse has somehow accelerated. Newly created social media platforms connected the world, populist politics returned, and the climate crisis became an immediate threat rather than some vague, far-off event. The economy crashed, and the distance between the rich and poor became a gulf. Is it any wonder that filmmakers, novelists and artists have turned to the apocalypse to capture the anxiety of how it feels to be alive right now?

And it’s not just creators. Audiences are hungry for nightmarish, imagined (yet jarringly believable) futures. Sure, the global popularity of Netflix’s recent success Squid Game – in which characters “compete” with one another to win the abolition of their personal debut – is partially due to the reach of the streaming platform the show is distributed through. Still, international audiences are connected to the South Korean dystopian drama because we all know what it’s like to live under the cruel brutality of capitalism, no matter where in the world we’re streaming the show from.

“Is it any wonder that filmmakers, novelists and artists have turned to the apocalypse to capture the anxiety of how it feels to be alive right now?”

During 2020, at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, I turned to fictional apocalypses because I wanted to find a way to begin processing the genuine catastrophes that were happening outside my home, not just the pandemic but also our pre-existing, unequal political, economic and social systems which the impact of COVID-19 has only exacerbated. Ling Ma’s novel, Severance, is about a virus that turns people into zombie-like creatures who are forced to repeat their daily tasks – but it’s also about the seemingly inescapable contamination of late-capitalist globalisation. Reading about a protagonist who was, quite literally, facing off against her complicity in perpetuating America’s exploitative supply chain infrastructure helped me to process my guilty feelings as a consumer in the Global North. Soderbergh’s Contagion, about a virus which, as many viewers pointed out, shares traits with COVID-19, was a way of watching a contained, worst-case scenario pandemic from a harmless distance.

With its plots, characters, and narrative tricks, fiction is a safe way for us to think about the world around us. A TV show like Black Mirror can show us that, like its protagonists, we, too, live in an unfair, cruel society governed by money; Octavia Butler’s dystopian novel, The Parable of the Sower, can be a blueprint for grassroots, community-based solidarity; and the recent abundance of novels about the climate crisis, like Jessie Greengrass’s The High House, Jenny Offill’s Weather and Jeff VanderMeer’s Hummingbird Salamander, can help us process the grief of living through the sixth mass extinction.

“The world might continue to end, time and time again, but it’s how we choose to live in the post-apocalypse that will be the actual test”

We are living in despairing, desperate times. It is easy to be swept away in a wave of news headlines that keep rolling in: a virus we have to ‘learn to live with’ at the expense of those who are most vulnerable to it, increasing economic inequality, a worsening climate crisis which is already proving devastating for marginalised communities around the world. Turning to fictional apocalypses won’t improve our real situations by themselves, but these stories offer us alternative, brighter ways of thinking about ourselves, our politics and our societies. They can give us “what if?” scenarios of what our future might look like if we keep walking down the path we’re on – or they can show us different ways of living with one another.

Ten years ago, imagining the end of the world gave me the tools to begin handling my mental health. Apocalyptic desire didn’t “cure” it, but it did give me an alternative way of processing my anxieties which were very much connected to the real world around me. Imagining worst-case scenarios won’t save the planet – or yourself – but trying to understand the cultural fascination with our own annihilation can help us process the structural systems around us that bring about the existential crises of our times. The world might continue to end, time and time again, but it’s how we choose to live in the post-apocalypse that will be the actual test of whether or not our humanity will survive.