The story of Alexander Tekle: a young asylum seeker who died in Britain’s hostile environment

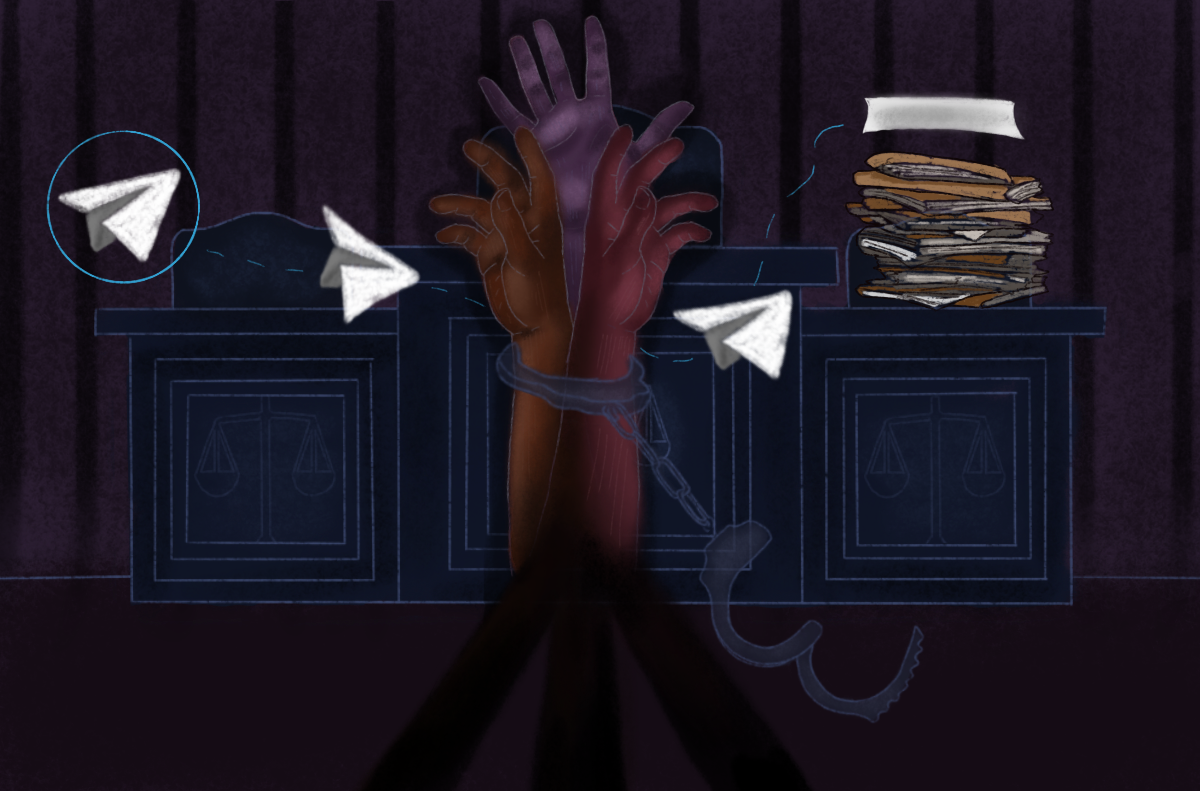

Five years after he took his own life, the inquest into the death of an Eritrean teenager revealed deep failings in the UK’s asylum system. With the introduction of the Nationality and Borders Act, it’s feared more tragedies will happen.

Dawn Limbu

07 Sep 2022

Javie Huxley

Content warning: This article contains mentions of suicide and self-harm.

It was an exhausting five-year wait for the inquest into the death of 18-year-old Alexander Tekle. Held virtually during COVID-19 safety measures in January 2022, the inquest felt distant and mechanical. Alexander’s father, Tecle Tesfamichel, logged in remotely from his home in Sudan, with the aid of a UK-based translator. He told the inquest he was concerned for his son after he fled Eritrea for his safety.

Alex, as he was known to his friends, arrived at the Kent docks in December 2016 having come to the UK via Libya and a refugee camp in Calais, France. Alex had been living in the UK for less than a year when a rapid decline in his mental health led him to take his life. Alex, an unaccompanied minor, had left his family behind in search of a better life, but when he arrived on British soil seeking asylum, he was treated as an adult. The adultification of Alex prevented him from accessing children’s services and support, contributing to the deterioration of his mental health.

“Alex had been living in the UK for less than a year when a rapid decline in his mental health led him to take his life”

Alex’s death in 2017 was not an isolated case. He was one in a friendship group of four Eritrean boys who took their own lives after seeking refuge in the UK. 19-year-old Filmon Yemane died a month before Alex, and two years later, 19-year-olds Mulubrhane Medhane Kfleyosus and Osman Ahmed Nur also took their lives. The deaths of these teenagers have raised the alarm about the way asylum-seeking children are treated in the UK, often mistaken as adults and denied proper care and treatment. Yet campaigners say the government has done little to address these issues.

It is feared the situation will worsen for these asylum seekers due to the introduction of the Nationality and Borders Act, which became law in April 2022. The legislation has been criticised by human rights activists for being discriminatory and unlawful. It introduces a stricter protocol for age assessments, meaning many more children could be wrongly identified as adults and subsequently placed in adult accommodation and miss out on education. Additionally, the introduction of a National Age Assessment Board comprised of social workers will blur the lines between immigration control and safeguarding.

Lost opportunities

At the inquest, the coroner, Bernard Richmond QC, found “that opportunities were lost before and after Alex’s 18th birthday to provide him with the help and support that he required”. The uncertainty over Alex’s asylum status and the loss of a close friend caused his mental health to worsen. In the months leading up to Alex’s death, social services had been made aware of his declining health, “but did not put in place effective strategies to address these issues,” Richmond said.

Charities and campaigners think that there may be many other asylum-seeking children who have taken their lives due to the hostile immigration system, the precarity of their immigration status and a lack of adequate social care. Yet the true scale of the problem is difficult to know for sure.

“gal-dem can confirm via Freedom of Information requests that five Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC) aged 14 to 25 died by suicide between 2018 and 2022 in the UK”

Da’aro Youth Project, a small charity which works with asylum seekers from the Horn of Africa (Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia), has identified more than a dozen deaths of asylum-seeking children since 2016. According to written evidence, Eritreans and Ethiopians combined were the largest nationality group of unaccompanied minors to arrive in the UK in 2017, 2018 and 2019. Many young Eritreans are thought to be fleeing compulsory military conscription that starts at the age of 18.

gal-dem can confirm via Freedom of Information requests that five Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC) aged 14 to 25 died by suicide between 2018 and 2022 in Leeds, Hertfordshire, Solihull, Kingston-Upon-Hull and the London Borough of Camden. Several other local authorities have indicated records of deaths by suicide amongst UASC but refused to share the information under Section 40 of the Freedom of Information Act.

“I have seen people who came seeking a better life and better opportunities end up losing hope and every motivation left, and become so depressed”

Roman

The deaths of the four teenagers and the lack of care they received after arriving in the UK has highlighted that unaccompanied minors from the Horn of Africa are a particularly vulnerable group. Roman (who did not want to use her last name) is the admin of a Facebook group titled ‘Ethiopians in London’, where she shares news relating to the community. Roman tells gal-dem that she was aware of the death of Alex and his friends and says she has encountered many Eritrean and Ethiopian refugees who have faced significant hardship in the UK.

“I have seen people who came seeking a better life and better opportunities end up losing hope and every motivation left, and become so depressed,” she says. “Even when life gets better, they still live in the darkness. The biggest worry and struggle most of them face is the wait [for the outcome of their asylum claim].” The worsening hostile environment indicates that we could be on the verge of witnessing a refugee protection crisis, with under 18s particularly at risk.

‘He seemed to be self-destructing’

Benny was 23, working as a project coordinator for Da’aro and volunteering in a refugee camp when he first met Alex in 2016. Benny told the inquest that Alex appeared to be 16 years old when they met, describing him as someone who looked very “tired, anxious, easily upset and very child-like.”

The two became good friends while in the Calais refugee camp, where Alex was waiting to make the final leg of his journey to England after travelling from Eritrea to Libya. Alex arrived in England in December 2016 and during his time living in Croydon and Kent, he remained close friends with Benny. Benny saw the challenges Alex was facing; despite having no previous understanding of child protection, child safeguarding, social care or the asylum system.

At the inquest into Alex’s death, the coroner concluded that “the degree of care that Alex received was affected by issues relating to his age”. Alex’s age assessment meant he wasn’t entitled to access children’s social services, exposing him to dangerous situations and vulnerabilities as he was placed in unsuitable accommodation.

“Alex’s age assessment meant he wasn’t entitled to access children’s social services, exposing him to dangerous situations and vulnerabilities”

On 19 April 2017, he was attacked by someone on the street while he was sleeping rough. This was not an isolated incident. Over the following months, Alex descended into a spiral of heavy drinking, self-harm and suicidal ideation. By early July, Alex was hospitalised after being stabbed. He returned to hospital in mid-July to receive treatment for alcohol-induced hyperglycemia. “He seemed to be self-destructing,” Benny says. Throughout these incidents, Benny continued to notify social services of Alex’s mental health, and was alarmed by the lack of support for a young person clearly in crisis. On 6 December 2017, Alex took his own life.

Since Alex’s death, Benny has been working with Da’aro to lobby the government to investigate the suicides of his friend and others. Da’aro has uncovered 13 young deaths of asylum seekers over a period of eight years. Some of these children were known to staff at the charity, or to friends of young people who have accessed their service.

“Da’aro has uncovered 13 young deaths of asylum seekers over a period of eight years”

Da’aro has attempted to gain information surrounding these deaths from multiple avenues, including the Home Office, the Office for National Statistics and the Department of Education. However, coroners are not required by law to record the deceased’s nationality or immigration status. When gal-dem asked for information about suicide among asylum seekers, the Office for National Statistics said: “In the case of suicides, deaths are always referred to and then investigated by a coroner. Whether or not the deceased was an asylum seeker is not consistently recorded by the coroner’s investigation.”

Benny feels that without this information, nothing can be learned to improve the well-being of these children. “The concern it raises for me, is the serious lack of publicly available data on this issue of deaths of care leavers generally, but specifically data that might reveal patterns,” he says.

Arrivals in the UK

When 20-year-old Moussa (who requested not to use his last name due to safety concerns) arrived in the UK at the age of 17, he felt safe, and happy about starting a new life. However, this new found safety was crushed the minute border officers decided that he looked like a 24-year-old. Moussa felt defeated and didn’t know what to do next.

According to Bridget Chapman, a media lead at Kent Refugee Action Network, problems continue for asylum-seeking children when they arrive on British soil. “The kids that arrived recently said they were cold and wet and left in warehouse areas of the Kent docks in wet clothes,” she tells gal-dem.

As soon as asylum seekers arrive in the UK, they are interviewed by Home Office officials to verify their story. “They often have to do initial interviews not long after arriving by boat, after not having a night’s sleep,” says Bridget. “The tipping point is when you arrive in a country and are left in your wet clothes with your injuries and motor fuel on your skin,” she says, and adds that children are usually placed in hotels on arrival.

All asylum seeking children will go through an age assessment process, but with most young people arriving without identification, it can be difficult to prove their age – especially if they come from a country such as Afghanistan where most people do not have a registered date of birth.

Bridget explains how children may have to undergo the interview process several times, and there can be a long wait until the official interview which decides the outcome of the asylum claim. “Children need to be put in an appropriate setting with people who can look after them,” she says.

Moussa had to sleep in a chair for three days after his arrival in London. “I spent three days with not any cover, not any bed, not any pillows,” he says, adding there were more than 15 people sleeping in chairs without blankets.

“I spent three days with not any cover, not any bed, not any pillows”

Moussa

The Home Office has been criticised for adopting ‘scientific’ age assessment measures that campaigners say are inaccurate and unethical. Children who have been deemed to be adults find themselves living in adult accommodation, struggling financially and unable to access the right support and education. While waiting for the outcome of their asylum claim, many of these children become very depressed due to the uncertainty that they face. According to the Refugee Council, 61% of asylum seekers experience serious mental distress, while refugees are five times more likely to have mental health needs than the UK population.

For unaccompanied minors, sharing the story of their journey to the UK carries a heavy weight. “Young people will describe losing themselves. They don’t even know who they are. They just feel trapped in their stories,” says researcher Jennifer Allsopp, from the Becoming Adult project. Becoming Adult’s research found uncertainty over status has a profound effect on the well-being of these children. Jennifer says she has worked with young people who she describes as “stuck in a perpetual present”, unable to think of their past or future.

Some asylum seekers have waited as long as 10 years for the Home Office to make a decision on their claim. Moussa told gal-dem that he met an elderly man while in adult accommodation that waited 15 years for his refugee status. “He has a lot of mental health problems,” he says, going on to share his concerns for a young friend who had his refugee application rejected. “I’ve not seen him for a couple months now and I don’t know where he’s gone. I’m very worried.”

Pushing for change

Benny says that when it comes to government policy, nothing has changed since Alex’s death. “Since Alex died, it has become more hostile, more aggressive. The number of age disputes has increased.” Figures from the Home Office show that the number of age disputes increased from 853 to 2,517 between 2021-2022. “I don’t think Alex’s death has been a wake-up call for anyone,” Benny says.

A Home Office spokesperson told gal-dem: “Each of these deaths is a tragedy. We take the safety and welfare of those in our care, including unaccompanied asylum-seeking children, extremely seriously and work closely with local authorities to ensure any care needs are addressed by statutory agencies.”

“I don’t think Alex’s death has been a wake-up call for anyone”

Benny Hunter

Yet these comments seem at odds with the wider Conservative Party approach to immigration. The 2022 Borders and Nationality Act has made it a criminal offence to knowingly cross the UK Border illegally. 22 August 2022 saw a record number of channel crossings by boat, with 1,295 asylum seekers arriving in the UK that day – including babies and young children. During her leadership election campaign, new Prime Minister Liz Truss has said that she supports and would extend the Rwanda deportation scheme. Combined with the government’s plans to impose stricter age assessments, unaccompanied minors are at a high risk of further persecution, and some children may be swept up in these deportations.

Alongside these harsh immigration policies and the threat of age-disputed minors being caught up in the deportations to Rwanda, charities and organisations are calling for systemic change to protect the lives of vulnerable young people.

“22 August 2022 saw a record number of channel crossings by boat, with 1,295 asylum seekers arriving in the UK that day – including babies and young children”

In an open letter sent in July 2021, Da’aro and 46 other organisations wrote to the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), stating that the UK is suffering a “refugee protection crisis” and asking for better protection of refugee lives. Da’aro also called for closer monitoring of deaths among unaccompanied asylum seeking children, to allow for social care processes to be reviewed. In December 2021, a senior civil servant from the Department of Education wrote to Da’aro stating that a public review would be needed before they can make any changes in how they gather information on the deaths of care leavers. At the time of writing in September 2022, Da’aro has not heard any further updates from the DHSC.

Da’aro is determined more than ever to support young Eritrean and Ethiopian migrants. “The one positive thing for me is that we set up a youth club in Alex and his friends’ names. We have more group activities, have started to take on casework and gained five staff members and 15 volunteers,” says Benny.

For Alex’s parents and three sisters, the time since his death has been a period of grief, heartbreak, and uncertainty. Tecle Tesfamichel felt relieved when his son made it to the UK. He told the inquest that he wanted Alex “to be safe in the UK. To go to school, get an education, and get married someday,” describing his son as a loveable and social boy who had a brilliant sense of humour and a compassionate nature. He was devastated to hear that his son’s journey to build a new life did not go as planned.

The death of Alex and his friends has highlighted the urgent need for systemic change to help protect vulnerable young people, yet the government is failing to collect adequate data on these deaths. Campaigners fear many more young people like Alex and his friends will likely continue to arrive on UK shores without their parents, without the care and support that they need, and without action from the British government to prevent further tragedies.

For more information and to support charities working with and campaigning for asylum seeker and refugee rights, check out the following organisations:

- Da’aro Youth Project

- Kent Refugee Action Network

- Positive Action for Refugees and Asylum Seekers

- Refugee Council

- Coram

- Social Workers Without Borders

- The Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or you can email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org. Text SHOUT to 85258 from anywhere in the UK, anytime 24/7, about any type of crisis, including suicidality.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?