Khadija Said

Young Black men are being jailed over text messages

In the UK, groups are being found guilty of violent crime ‘by association’ and accused of being in gangs, sometimes based on their music taste or messaging history – despite not committing the act itself.

Ruchira Sharma

20 Dec 2022

Ademola Adedeji was a model teenager – impressive in a way many parents could only wish for their child. Head boy at his school, he had an unconditional offer to study law at a Birmingham university, worked as a care worker for people with dementia on weekends, and was invited to parliament in 2019 after writing a book which profiled inspiring local young Black people.

But the path ahead took a tragic turn in July this year when the 19-year-old from Moston, north Manchester, was one of 10 young men convicted for being part of a conspiracy to enact violent revenge for their friend who was killed in a machete attack on 5 November 2020.

He and three other friends, all of whom were 19 at the time, didn’t own any weapons, take part in any violent activity or engage in “scoping missions” to locate victims, the Guardian reports, but they were in a Telegram group with people who did. The group chat was set up by another defendant hours after their 16-year-old friend, aspiring drill rapper Alexander John Soyoye, was murdered in 2020. Simply being part of a messaging group cost the three young men eight years in jail for conspiracy to cause grievous bodily harm.

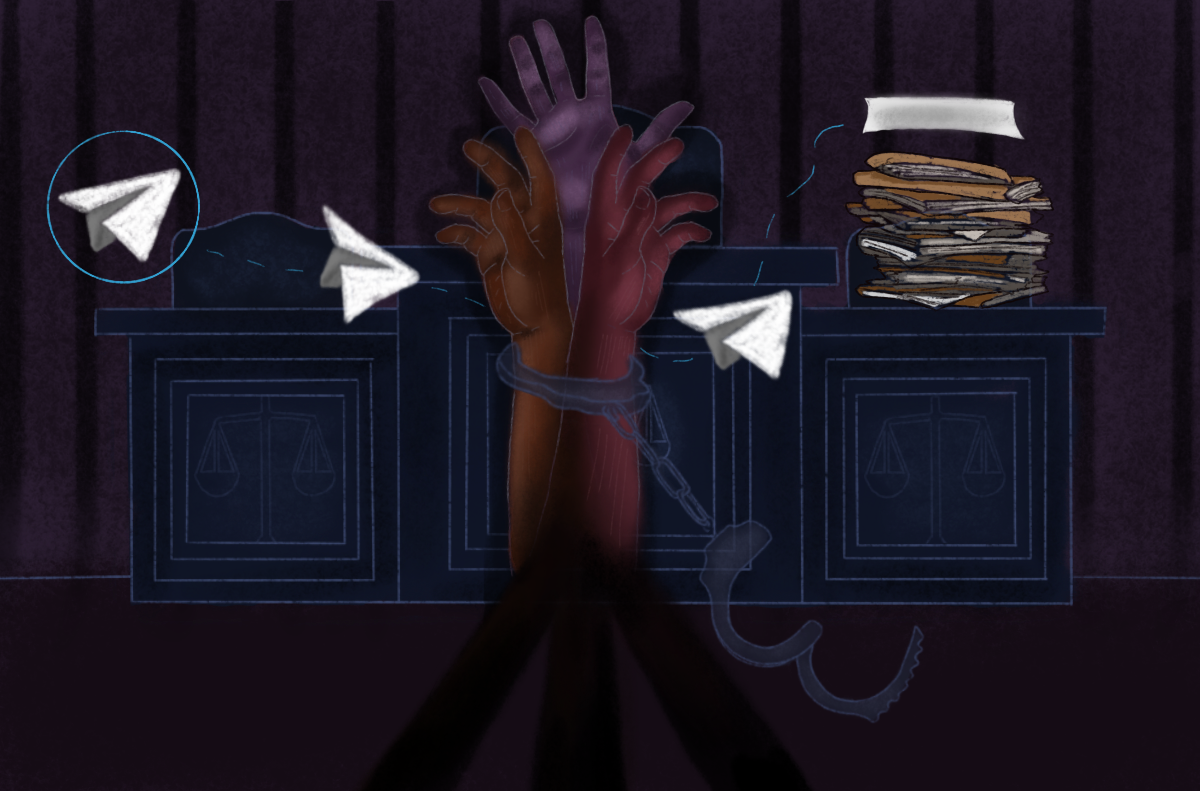

The case was tried under conspiracy legislation, but activists say this was yet another example of being ‘guilty by association’, and mirrors crimes prosecuted in the UK as ‘joint enterprise’. Joint enterprise isn’t a charge by itself, but a set of legal principles which can be used to prosecute multiple people for a single crime. The 300-year-old common law doctrine became well-known following the 1952 trial of Derek Bentley who was hanged for the murder of a police officer, though he didn’t fire the fatal shot.

Joint enterprise allows prosecutors to lump defendants together as one unit, and often label them a gang – a term research has shown is disproportionately used against Black men. In the Metropolitan police’s Gangs Matrix, a database of suspected gang members in London launched in 2012, 72% of those identified as responsible for ‘gang flagged violence’ are Black. Yet, in 2021, London mayor Sadiq Khan’s review into the database found 38% on the list posed little or no risk, resulting in one thousand young Black men being removed from it.

“There’s no escaping the ‘gang’ label, one of the most damaging labels possibly applied to young Black boys today”

Roxy Legane

Joint enterprise is being widely used against Black people in the UK, with data from the New York Times finding Black defendants are three times as likely as their white counterparts to be prosecuted for homicide as a group of four or more. An earlier study released in spring 2022 found that, of young male prisoners serving 15 years or more for joint enterprise convictions, 38.5% were white and 57.4% were Black, Asian or an ethnic minority (BAME) – despite these groups accounting for less than 6% of the population.

In theory, joint enterprise should be used to prosecute people who assisted in a crime, for example, holding down a victim who is being attacked. But the application of joint enterprise is less clear-cut. In reality “association” – a relationship between defendants – is used to highlight intent. It means an individual’s taste in music, the number of times they’ve messaged someone, or their proximity to one another at the time of an incident are all used to convince a jury of their ‘bad character’ or relationship to a gang. It has led to people being convicted of murder or manslaughter even if they did not play a pivotal role in the act itself, including bystanders. Whole groups can be convicted of a ‘gang’-related offence committed by one person, on the back of what many believe to be prejudicial evidence – like being involved in drill music.

Adedeji and the three other friends were all convicted based on the fact they’d sent messages on a group chat they had joined three days after their friend was murdered. The Telegram chat was created by another defendant, Jeffrey Ojo, and some of the conversations discussed retribution. The prosecution claimed all 10 boys were plotting revenge there; but of the group’s 345 messages, Adedeji and another friend sent a combined total of just 22.

“This story is another in a long line of joint enterprise or ‘guilt by association’ themed cases that will continue to take place across the UK,” says Roxy Legane, the director of Kids of Colour, who attended the trial. As soon as these boys were charged, there was “no escaping the ‘gang’ label, one of the most damaging labels possibly applied to young Black boys today.”

A judge claimed Adedeji and his four friends were members of a gang. But this could not be further from the accounts of people who knew him. An anonymous friend from secondary school described him as “the biggest and strongest in our group then, but we all knew he was soft inside”. Ademola “kept me on track”, they added. “A strong role model like Ade should be in our community helping other young people, like he was before, encouraging them to pursue healthy things for themselves.”

Adedeji’s positive influence on people around him was palpable. But he’s now been taken from the community; his dreams put on hold.

***

Just a 20 minute drive away from Moston, five years previously, a group of 11 young men, all mixed race or Black, were jailed for a total of 168 years for their part in the killing of Abdul Hafidah. During the incident in 2017, some of the group chased Hafidah, others assaulted him and ran off. Reports state two were present when one stabbed him and caused the knife wounds which led to his death. The prosecution alleged all 11 men were all in a gang, and used a drill video they’d appeared in the year before as evidence. But this video was in fact organised as part of a publicly-funded youth project whose partners included the Greater Manchester police, according to the Guardian.

This case took place a year after what campaigners had believed to be a landmark ruling against joint enterprise. In 2016, the UK’s highest court announced that the test used to determine guilt in joint enterprise cases – where the person accused assists the killer but does not carry out the lethal act – had been incorrectly applied for 30 years. It was concluded that courts had wrongly interpreted the fact that a secondary, co-accused individual had foresight that the primary attacker might carry out a killing as sufficient proof of guilt.

Jan Cunliffe is the co-founder of JENGbA (Joint Enterprise Not Guilty by Association), a grassroots campaign group that supports approximately 1,400 prisoners (mainly those serving life sentences) convicted under the joint enterprise doctrine. In 2008, when he was 16, her son Jordan was convicted of murder and given a life sentence using joint enterprise. He claimed to have been present during the attack but never physically engaged with the victim, who died due to a single injury to the neck. The other 16-year-old who delivered the lethal blow confessed, and another boy, who was 18 at the time, pleaded guilty to manslaughter.

Jordan is partially sighted, and maintained he could not see his friends attacking someone, or run away, as a result. After spending 13 years in prison, he was released on a life tariff. Throughout her campaigning, his mother still had to endure years of incredulity from friends and acquaintances when she explained joint enterprise’s role in her son’s conviction.

“How can that happen to someone who the trial process proved didn’t actually kill anyone?”

Jan Cunliffe

Cunliffe has spent 13 years campaigning for people unfairly convicted under joint enterprise. But a November 2022 investigation from The New York Times revealed that convictions under joint enterprise have in fact increased significantly in the last six years, despite the 2016 Supreme Court ruling. Cunliffe says she felt heartbroken at the news. “To some degree, I felt like the campaigning [we did] made them dig deeper as a form of revenge. And now they’re making it worse. It’s a torment.” She knows families are reliant on her organisation to campaign and raise the profile of joint enterprise, but says “you’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t – that’s what it feels like”.

But there’s a reason she keeps campaigning – “at one end, we’ve got lots of families with the greatest stories of injustice, and they want to appeal, but they feel that if they go public, then the judges will come down harder on them.” Many fear that if they speak up their child will never be released. “And that’s the hold that the system has on all of these people right now. It’s like, we will lock you up, and we will also silence you,” she says.

Cunliffe has come across thousands of families whose children have been convicted under joint enterprise. One thing families struggle to accept is the length of the sentence for their loved ones, who are often very young. “It’s like, well, I’ll be dead by the time he gets out of prison,” she says. “How can that happen to someone who the trial process proved didn’t actually kill anyone?”

One relative who came to Cunliffe for support was Les Jones. In 2021, his grandson Sebastian Jones was convicted of murder, assault occasioning actual bodily harm and violent disorder at age 19. Along with five other young men, he was jailed for life with a minimum term of 17 years, after a brawl outside a Dudley pub led to a man’s death. Local media reported Sebastian told the court he had initially tried to restrain his friend, but punched the victim a handful of times in the back and claimed he was then pulled into an alcove, away from the incident.

Sebastian’s family are in turmoil. Jones has paid thousands of pounds for transcripts of court proceedings and revised CCTV footage, and cannot believe the outcome – 70 years of his grandson’s life for what he says was “17 seconds” of defending a friend.

“With joint enterprise, the police pick the victims and that’s why they know they can get away with it,” Jones says. “They know they’re working class; they know they haven’t got money. They know they can’t fight because they certainly can’t get an appeal and you can’t pay the top lawyers and barristers to fight for that for you.”

Breaking down in tears over a Zoom video call, he says his daughter, Sebastian’s mother, is on antidepressants and suffers extreme mood swings in the wake of his sentencing. He and his partner feel forced to live their lives – there is no other choice. But unlike “a bereavement, there’s no finality” in this situation, he says. The only comfort they have is talking to other families whose children are in prison because of joint enterprise.

***

Author Emeka Egbuonu is a former Hackney youth worker whose role involved outreach with kids on the periphery of violence. More than half of young people in custody are BAME, official government figures showed last year, and campaigners believe this has been made worse by ‘guilty by association’ convictions. Joint enterprise “makes police work a little bit more lazy, because it’s just easy to group everyone together and you don’t really have to know the context of who did it,” Egbuonu says. “Because you’re all together, by default, you have secondary liability for somebody else’s actions.” Egbuonu makes the point that phone calls and online communication can act as evidence for association too, even if someone isn’t physically present during a crime.

He used to advise kids to be smart about their friends to try and protect them from getting caught up in these situations. “Much of the messaging was just what our parents used to tell us. Just make sure that you’re around people that you can vouch for and just be careful who you’re hanging around with,” Egbuonu notes.

Now his battle is to show vulnerable kids that they “have something worth fighting for and something to lose, i.e. a qualification and education”.

But it shouldn’t fall to youth workers to tackle this. Dr Susie Hulley, a senior research associate at Cambridge’s Institute of Criminology, says it’s essential to highlight the harmful reality of joint enterprise. She explains: “Part of the work that needs to be done is establishing what we should be doing differently.”

“Black and brown young people will become the targets in a country now committed to child prisons and a profitable prison industrial complex”

Roxy Legane

Hulley says it’s clear, having worked with prisoners for several years, that with joint enterprise both the conviction and the sentence are devastating. “It’s being called a murderer, [even] if you haven’t committed any fatal violence or any serious moments, and it’s serving a very long sentence for something that you don’t think is fair.”

The label changes everything. Even in jail, in order to be released from a life sentence an individual has to prove they’re no longer a risk. One way prisoners do this is through taking responsibility for their crime and showing remorse and guilt. For people charged under joint conviction, their charge won’t be being an accomplice or secondary party, it will be murder, Hulley says. But how do you take responsibility for a crime you didn’t commit?

JENGbA argues that a change in the law is the only way to ensure justice. The first reading of a Private Members’ Bill to get rid of the ‘substantial injustice test’ – a test to determine whether someone should have an appeal – took place this September, and passed its first reading. Experts say the ‘substantial injustice test’ acts as a barrier to those wishing to challenge joint enterprise convictions. The next reading is scheduled for 20 January 2023.

In April 2022, human rights organisation Liberty announced it was taking legal action against the Crown Prosecution Service and the Ministry of Justice over Joint Enterprise on behalf of JENGbA. “It’s completely unacceptable that there is still no official data being recorded about how the doctrine is used, and who it is used against,” Lana Adamou, a lawyer at Liberty, said in a statement. “By failing to do so, the justice system has been recklessly sweeping thousands of young Black men into the prison system.”

The number of young people (aged 25 or younger) sentenced to life imprisonment with at least 15 years in prison increased by more than half between 2013 and 2020, from 917 to 1,394 individuals. In November 2022, the government recognised, reportedly for the first time, that joint enterprise impacted “some groups disproportionately”. The impact of the joint enterprise doctrine is far-reaching and cuts individuals’ futures short, but also devastates the people surrounding them. It tears children and teenagers away from their families and disproportionately impacts young people of colour – many of whom are given murder charges despite never having committed murder.

“Black and brown young people will become the targets in a country now committed to child prisons and a profitable prison industrial complex,” says Legane, who campaigns on behalf of some of the boys convicted in Manchester this summer. “And it is done on purpose, by an authoritarian state whose core focus is oppressing the racialised to uphold power and white supremacy.”

Follow Kids of Colour here, and JENGbA’s petition to acknowledge how joint enterprise has been used wrongly here.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?