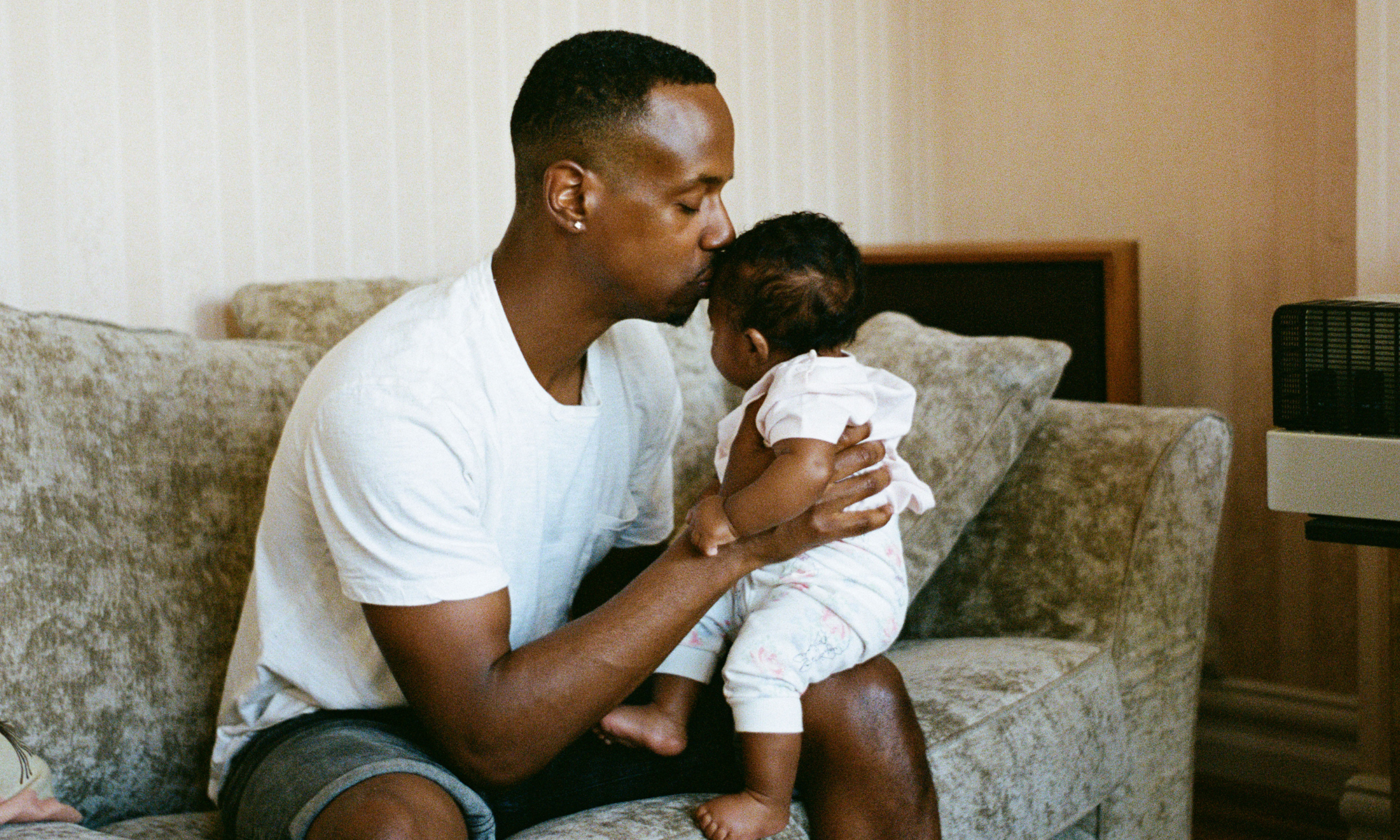

'Flotation' by Tyler Mitchell

Tyler Mitchell’s Chrysalis exhibit explores Black people’s mystical relationship with nature

As the wunderkind opens his sophomore show at the Gagosian, he’s cementing his final form as an artist who creates dreamscapes, visualises psychological states and values feeling over fact.

Precious Adesina

04 Oct 2022

In a new photograph by Tyler Mitchell, a shirtless boy sits in nature looking cross-eyed at a large beetle resting on his nose. In everyday life, an insect landing on your face would be uncomfortable for most, but in the 27-year-old New York-based photographer’s image, it is a captivating and serene moment. His subject has a relaxed demeanour, and the vibrancy of the stunning greenish copper colours of the beetle’s shell is in full view.

Tyler’s Simply Fragile (2022), taken for his upcoming exhibition, Chrysalis, at the Gagosian in London, directly references Gordon Parks’s 1963 image, Boy with June Bug, Fort Scott, Kansas. Tyler describes June Bug as “bucolic and beautiful, but also kind of menacing” over Zoom, sitting outside on a patio chair in the corner of a garden. In June Bug, an even younger Black boy than the one in Tyler’s picture is lying on the grass, pulling a giant insect across his face with a white string. Parks used this shot for his photo essay in Life magazine titled ‘How It Feels to Be Black’.

Chrysalis at the Gagosian is Tyler’s second gallery show, a name he believes perfectly sums up where he is at in his career. “Everybody’s second show is the hardest,” he says, noting that it’s the point a person needs to properly think about where they’re heading artistically. The term relates to the state that occurs just before a caterpillar becomes a butterfly, it is a maturation, a transition to a final form. “I thought of the idea of Chrysalis as this sort of cocooning, meditative state.”

Tyler seems hyperaware of how anticipated this exhibition is for people in and out of the art world. The photographer has been a household name since 2018 when he became the first Black person to shoot an American Vogue cover at just 23 by snapping Beyoncé in a flower crown for the September issue; a huge feat for a publication that has existed for over 125 years. Around a year later, he had his first solo exhibition in Amsterdam titled I Can Make You Feel Good, which was later also shown in more than one location in the US. He was awarded Forbes 30 under 30 that same year and has now collected many more accolades, including BET‘s Future 40 list in 2020. His playful fashion photographs of high-profile people such as Harry Styles, Kamala Harris and Dua Lipa have now graced the cover of Vogue on multiple occasions. Considering that the name of the new show implies this was his belly-crawling era before taking flight, it’s inspiring to think of what his next creative stage of development will entail.

“Tyler’s rise has been nothing short of meteoric,” says Antwaun Sargent, a director at Gagosian, friend of Tyler’s and author of The New Black Vanguard, which interrogated a new photography movement via Black rising stars behind the lens. Over email, in between his busy schedule, he waxes lyrical about the photographer who he included in the anthology of genre-shifting artists. “There is an intense maturity in how he has continually examined these deep moments of pleasure and devastation since he and I met in 2018.”

For many artists, the weight of such achievements so young could be suffocating. Many creative masterminds whose careers skyrocketed at his age are somewhat hesitant to change for fear that they might lose the edge that brought them notoriety in the first place. But Tyler isn’t one of these people. “I’m really excited by the fact that this work is new,” he says of his latest photography collection. “It feels stronger, packs more of a punch, but it’s not didactic,” he adds. “The work is getting looser, hopefully, more mature and sophisticated.”

“I’m interested in and excited about exploring pictures that can come from more of a psychological state rather than one’s bound in facts or clothes.”

Aspects of the themes that brought Tyler his notoriety will feature in his second show. He first explored the idea of ‘Black utopia,’ where he envisioned what joy would look like for Black people if they hadn’t been historically denied their freedoms. In an Untitled piece from 2019, attractive young models lie down, their eyes closed, on a picnic blanket, basking in the afternoon sun. In another, Untitled (Park Frivolity), a couple relaxing on the grass whisper to each other. But now, Tyler’s use of colour is more robust, his techniques are more refined, and his style is becoming evermore identifiable. Whereas previously, his imagery worked as standalone pieces, in this exhibition, each work seems to be having a conversation with the others. Land, water, and sky (either artificially or naturally) are present in each photograph.

Tyler says people are often bogged down by the need to uncover basic information about an image, such as its location, when it was made, and who the subjects are. “So many people with photography shows ask you all sorts of fact-based questions before they allow themselves to enjoy the craft of an image or what it is saying emotionally,” he says. “I’m interested in and excited about exploring pictures that can come from more of a psychological state rather than one’s bound in facts or clothes.” Tyler also explored emotive photography in this manner with the playwright Jeremy O. Harris for Vogue Italia in 2020. The Afrosurrealist project, which was commissioned in response to the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, was inspired by Dadaism and entitled ‘Black nonsense’ and suggested that nonsensical imagery could be a source of joy. It’s interesting that at a time when media called upon black creatives to voice their trauma Tyler instead explored a space to envision what freedom looks like. Clearly, Tyler’s art is driven by a want to visualise psychological, abstract, and subconscious desires from a black perspective.

Nature is a particular focus in this collection of work, which Tyler attributes to his upbringing in Atlanta, a city in Georgia where almost half of it is covered by trees. “It’s a city in a forest,” he says. “Growing up as an only child, a lot of my free time or outdoor reflective time was in nature, so I was both seduced by it and captured by its beauty.” But as he got older, he also learned about the “atrocities” in Georgia. In 1912, white mobs in Forsyth County violently drove out its Black population and fiercely guarded its borders for much of the 20th century. “These pictures think through the ways Black people relate to land and both the seductive nature and beauty of the Southern landscape, but also the sort of threatening elements.”

As such, mud is an integral element in multiple images in Chrysalis, which plays a vital role in highlighting the duality of land and nature that Tyler speaks about. In Flotation (2022), a boy flails through the mud as if swimming in water; In Rapture (2022), his hand shoots out of it. The light also glistens off the model’s skin and the wet earth in each photograph. “Those images are quite eerie and quite mystical,” Tyler says, adding that he believes they reference many things, including Black struggles and Black people’s relationship to water, rituals, baptism and bathing. “The stark and powerful image of a Black figure swimming through mud calls forth all these connotations for me, so hopefully, it’ll do the same for other people.”

For many, the show will solidify the fact that Tyler is no longer ‘one-to-watch’ or ‘emerging,’ but an established artist with a distinctive style whose idiosyncrasies command your attention. A photographer breaking free of any creative moulds or industry constraints.