by Pixy Liao

A Chinese-Japanese couple use photos to question gender, power, and nation

Pixy Liao’s Your Gaze Belongs to Me objectifies in order to liberate.

Tiffany Tso

21 Feb 2022

Whenever I imagine myself posed with my lover, I think of Yoko Ono and John Lennon on the cover of Rolling Stone: I am an Asian woman, fully clothed and lying on my back, while my partner is nude, vulnerable, and cradling their body onto mine, holding my face adoringly, kissing my cheek. In a more extreme depiction of our romantic dynamic, photos featuring Asian dominatrixes might suffice, with their submissives on leashes kissing their patent leather stilettos as an act of worship. These are the existing images within pop culture and art that actually resonate with me, considering that most of what we see of Asian femmes in Western media relies heavily on tropes crafted by a white male gaze that fetishizes or disempowers us. That is until I viewed the first solo museum exhibition by Pixy Liao entitled Your Gaze Belongs to Me at Fotografiska in New York City.

A lion’s share of the show’s works belong to ‘Experimental Relationship,’ a long-term project in which Pixy, who immigrated to the United States from China, composes and captures scenes of herself with Moro, her real-life boyfriend, a Japanese man five years her junior. The ongoing project explores and challenges traditional gender norms within heterosexual relationships, playing with themes of love, sex, power, and nation (given China and Japan’s fraught history).

In an act of transmuting a power shift into an image, we witness a bare-assed Moro, wearing an apron, splayed across Pixy’s clothed lap with his face obscured from view. Pixy, however, is making direct eye contact with us, the witness. This photograph, After Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (2019), is just one example of how the artist creates imagery that challenges our assumptions of what roles East Asian women can play in their relationships and within our collective imagination while evoking strong BDSM connotations. In You don’t have to be a boy to be my boyfriend (2010), Moro stands barefoot next to a shed wearing Pixy’s floral dress. In Spit (2014), Pixy is spitting what looks like a crystal spit droplet into Moro’s mouth. These images are evocative of dominatrixes engaging in forced feminization (also known as sissification) or humiliation play with their submissive partners.

Though the photos are clearly posed, there is a certain intimacy that can be gleaned from the images of Pixy and her lover – one that refutes hetero-patriachal gender norms dominant in both Chinese and American society, in both life and art.

According to the artist, the exhibition offers a disruption of gender roles. However, in viewing Pixy’s artwork through a lens of BDSM (bondage, discipline, dominance, submission, and sadomasochism), we are also able to gain an understanding of how these roles get conscripted, how to begin the process of unravelling them, and the freedom Asian men and women gain by doing away with sexual stereotypes.

Pixy explains of her relationship: “As a woman brought up in China, I used to think I could only love someone who is older and more mature than me, who can be my protector and mentor. Then I met my current boyfriend, Moro. Since he is five years younger than me, I felt that the whole concept of relationships changed, all the way around. I became a person who has more authority and power.”

What’s happening in these photographs feels illicit and alien to many, because of how the activities subvert gender norms especially within the context of heterosexuality. Gender play, like all of BDSM, is considered non-normative and taboo, because of society’s deep commitment to traditional ideals of masculinity and femininity.

In an interview, Pixy shares that she met Moro while in photography school and began using him as a “prop” in her photos for class assignments. “Sometimes I would ask him to play a dead body, or be naked and fit in a suitcase,” she says. “When my class saw my photos, the first thing they said was not about my photos, but, ‘How could you treat your boyfriend like that?’ I was surprised by their reactions because it was very natural for us. I asked my boyfriend to pose for me, and he did it. They are just photographs.”

It is possible that Pixy’s classmates had a difficult time grasping a healthy dynamic between an Asian woman and man where she is the artist and he is the muse (or prop). In Pixy’s creative world it is her gaze that objectifies the man. As a culture, we are seldom presented with this arrangement.

In popular Western media and culture, Asians are often depicted as one dimensional – foreign bodies to be derided, conquered, and consumed. Archetypes like the submissive and subservient ‘Lotus Blossom’, a porcelain perfect wife, or the ‘Hooker with a Heart of Gold’ dominate roles for Asian women on screen, stage, and page, and can be traced all the way back to the 19th century. These caricatures are still prominent today and impact how we are covered in mainstream media, as well as how we’re treated by the state and in our personal lives. Countless sting operations by the police envision all migrant Asian sex workers and massage workers as victims of sex trafficking needing to be rescued. White men who fetishize Asian women commonly state that they desire Asian women because they are more servile and less assertive than their white counterparts.

“I just don’t think all men are tough or need to be tough. It’s not fair to ask all men to be strong and stronger. I like them when they are softer”

When Asian characters have a modicum of agency, they are seen as (physical and spiritual) threats to white men – otherwise known as the cunning and sexually deviant “Dragon Lady,” another common Asian archetype and a foil to the Lotus Blossom. In fact, written into the earliest federal immigration restriction in U.S. history, via the Page Act of 1875, is a depiction of Chinese and other Asian women as prostitutes coming to America for “lewd and immoral purposes” and to spread venereal diseases to white men. Pixy’s artwork, on the other hand, could be seen as celebrating cunning, powerful, and seductive Asian women.

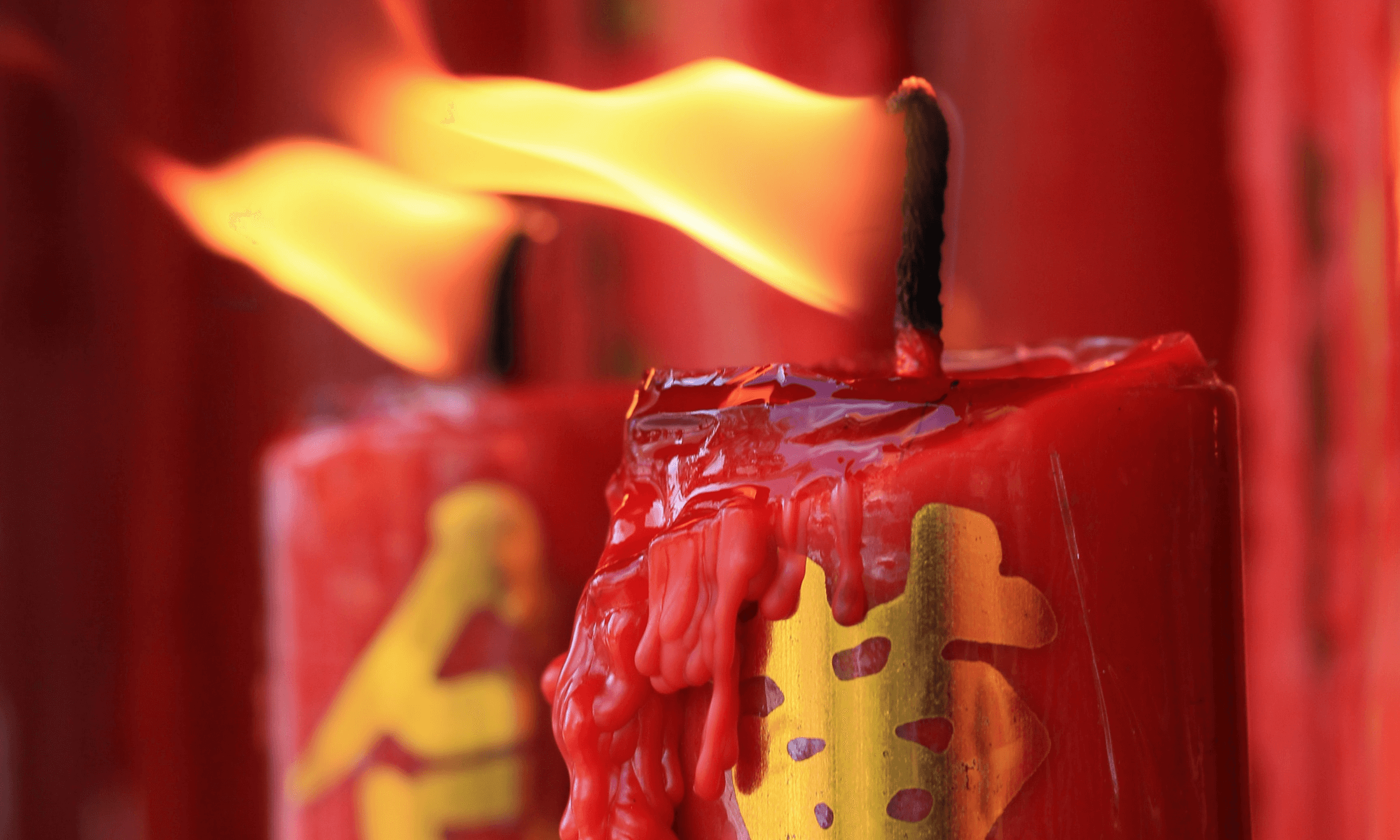

One room of Pixy’s show features pieces that are part of another ongoing project titled “Evil Women Cult,” which includes an altar to Wu Zetian, the only empress in Chinese history, and other symbols of female domination. Pixy is clearly cognizant of the villainisation of women who desire power and control, but her work attempts to rescript how we understand these “evil women ” and valorises them instead. Pixy believes we can learn from their strengths.

“I adore dominatrixes, but I have to admit that I’m far from being one. Our relationship is more fluid,” Pixy says. “In a traditional household sense, when a husband’s role is to make money and take care of the family from outside, my role might be more similar to a traditional husband’s role.” Growing up in Shanghai, Pixy says she had the model of the ‘house husband’, men who prefer doing household chores over professional work, which gave her hope that her journey didn’t have to align with traditional Chinese culture, which is generally highly patriarchal.

Your Gaze Belongs to Me could cause great discomfort. Visuals of an Asian woman treating her boyfriend like her submissive or plaything may even feel like an affront to masculinity for some viewers, especially when we consider how Asian men are often emasculated and asexualized in Western media. But the “Experimental Relationship” series is not photojournalistic or real-life documentation.

She also questions why strength is the only acceptable masculine trait. “I just don’t think all men are tough or need to be tough. It’s not fair to ask all men to be strong and stronger. I like them when they are softer. I don’t mind being a protector. It actually gives me joy. And it also provides safety for men,” Pixy says.

“My work is my self-exploration as a woman, what I want or wish to see, what I’m not seeing. I’m sure I’m not the only one who thinks like this. Maybe there are some people out there who, like when I was young … think of themselves as weirdos,” she says of her non-standard world view. “And they would think, ‘Oh, that’s similar to what I think, I’m not alone!’ We are not alone.”

Pixy Liao’s Your Gaze Belongs To Me is currently on exhibit at Fotografiska Stockholm until March 20, 2022.