Four Black British trans artists who are reimagining the future

Through performance, poetry and digital archives, these Black trans artists are pondering the possibilities of utopia.

Travis Alabanza and Hélène Selam Rose Kleih

18 Nov 2022

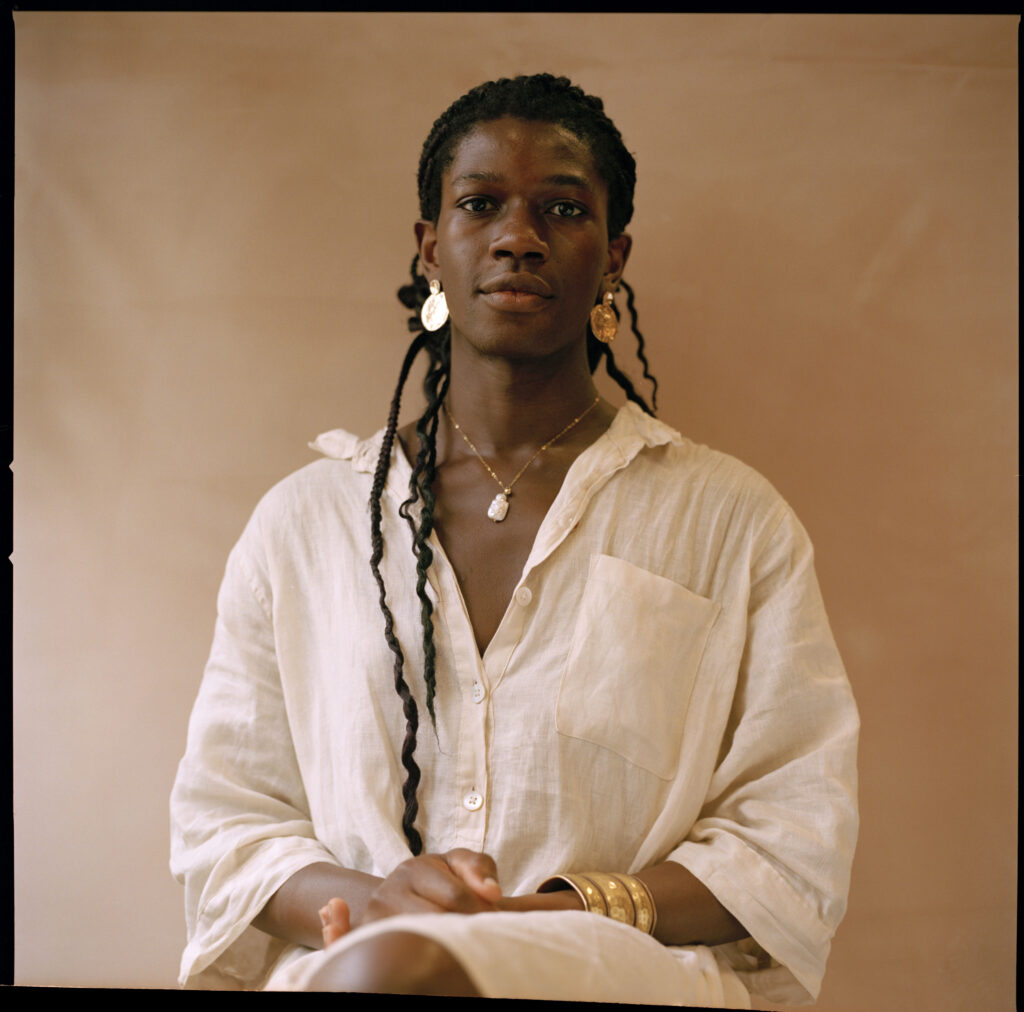

Ebun Sodipo. Image by Adama Jalloh, courtesy of V.O Curations

Art saved my life. I used to try and hide away from this almost cliché declaration as an artist; I’d try and place art somewhere in the background, somewhere after my friends, or food, or a lover. But, I believe I can experience these things because art first made it possible for me to still be here walking, breathing, laughing and growing.

When you are shown to the world as you are – and that are is a racialised, gender-nonconforming, trans (or whatever word you may want to use) person – the idea of no future reverberates back to you. It can feel hopeless, shameful and desolate. Depression feels like a logical answer to a world that is so devoted to not receiving you as the gift you are. But then, you find the art of others like you. Pouring out from their pages, sitting atop their stages, seeping into the fabrics of their canvases, or dancing between the melodies of their music is the very reality that you thought could not exist: that we have experiences that lie ahead, that there is more to come. That in itself is a utopia.

gal-dem spoke with four talented trans artists who are gazing into the future, daring to expand on the artistic horizons of our community and create a landscape where our existence is celebrated. — Introduction by Travis Alabanza, interviews by Hélène Selam Rose Kleih

Jacob V Joyce

Multidisciplinary artist Jacob V Joyce’s primary focus is “reclaiming connection” to land, histories and futures. By their own admission, they’re “amplifying historical and nourishing new queer, anti-colonial narratives”. In other words, the south London-raised artist commemorates the past to inform the future.

A tattoo of Olive Morris, the Brixton community squatters’ rights activist, proudly adorns their arm and embodies Jacob’s focus over the last year: a spaceship collectively built by activists and politically motivated artists for Black land activists, Black squatters and LGBTQIA+ people who have experienced homelessness. It was built during the pandemic to uplift, invigorate and co-ordinate strategies of resistance and is activated through games and grounding rituals. The mobile fabric mural, otherwise known as the “mother instrument”, was utilised in their series of workshops, Cruising Beyond Alienation, and most recently in April this year to aid the abolitionist education coalition NME (No More Exclusion) to hold an intervention at the National Education Union Conference in Bournemouth.

Rallying against the “ocean of amnesia” between themself and their trans ancestors through large-scale painted outdoor murals, Jacob seeks to archive the trans experience and admits that the omission of trans figures in history, such as sangomas (people who possess male and female spirits that have been respected and celebrated across East Africa for thousands of years), is “proof that we have already survived the apocalypse”.

“Utopia is a collective longing to find ourselves in the past, present and future. It’s the bubbling head of a fountain, the wet pulsing force of unborn possibilities”

Jacob V Joyce

Jacob’s utopia is “a defiant collective longing to find ourselves in the past, present, and future”. It is “the bubbling head of a fountain, swelling and bursting before it can be held, the wet pulsing force of unborn possibilities. We know that the capitalist, white supremacist, hetero-patriarchy loves to sink its teeth into our joy and shake it down to a soulless commodity.” Utopia to them is an act of resistance; it “has to be filthy, it must be criminal, evasive and able to evaporate when captured by the extractive gazes of power.”

Chloe Filani

“I’m a Black trans woman, living under the systems of white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, imperialism and cisheteronormativity,” says Chloe Filani. “I can’t move freely without having to see my utopia outside of these things.” A poet, performance artist, public speaker and workshop facilitator, Chloe works in various mediums to emanate “self-expression of love and acceptance”. She uses spoken word and performance as a vehicle to explore notions of identity and power dynamics both within and without imposed societal constructs, to reframe and rewrite her position in the world.

For Chloe, utopia is steeped in Blackness and queerness and void of ableism. “Utopia looks like Janet Jackson’s video for ‘Got Til It’s Gone’ – all different types of Black people, shapes, queerness, transness and disabled, creating, enjoying, dancing, playing and healed from trauma.”

Chloe’s poetry and writing intertwines her lived experiences as Black trans woman of Nigerian Yoruba heritage with ideas of precolonial trans femme ancestors as poetic heroines. “In my writing I have reimagined possible stories or folklore of Yoruba and Esan trans femme people and how they lived, loved and laughed, in their communities and in their families,” she explains. These poems will be made into a book for publication by the end of the year. “I couldn’t find stories of trans and gender-variant people in that culture but I know that culture would have had a different way of existing [in terms of gender]. Many Yoruba names are not gendered – Femi, Tolu, Toyin, for example – and it feels that there was an erasure of them and their stories. To imagine the past also allows me to imagine the future.”

She relates back to enslaved peoples, specifically Haitians, who “would have had to imagine themselves as free before they could even fight for that freedom”, adding that “imagination is important in getting to a place of liberation”. Her work with fellow artist and friend Ebun Sodipo constructs poetic fantasies, “working through real trauma to see beyond it”. Their performance pieces embolden others to dream.

Ebun Sodipo

Interdisciplinary artist and writer Ebun Sodipo is preoccupied by “those who will come after”. Her work and practice is engaged in ensuring that they have a “richer and less painful history to draw from as they build themselves”. When imagining the dystopia in her work, Ebun is brutally honest. “We usually think of dystopia as the destruction, the violent end of a civilisation and so many of us know that. In fact, most contemporary representations of dystopia mirror the violence that was wreaked on people of colour,” she explains.

“We usually think of dystopia as the destruction of civilisation. In fact, most contemporary representations mirror the violence that was wreaked on people of colour”

Ebun Sodipo

She’s fascinated by “what happens after dystopia” and “how people have fashioned themselves after the destruction of their home by colonisers who came from the sea”. Her work, such as the video collage And The Seas Bring Forth New Lands, interconnects the “legacies of colonialism, genocide and enslavement with my transition and the modern world”. The video appears alongside a French news report of infanticide in southeastern Congo carried out by neocolonial Japanese workers who were mining minerals used in the batteries of our phones and laptops, alongside images and sounds of Black trans women, and popular, and viral videos. Using imagery of volcanic islands with lava dripping into the sea to form new energy and land, Ebun creates both the sights and sounds of “Black joy in the midst of Black pain”.

Danielle Braithwaite-Shirley

Specialising in animation and interactive gaming, Danielle Braithwaite-Shirley recognises the power that technology has held “so that those in the future will have something to look back on.” Her recent exhibition, She Keeps Me Damn Alive, utilises her series of dotcom works, blacktransarchive.com, blacktransair.com and blacktranssea.com, as a depot for archiving the Black trans experience through the lens of interactivity and storytelling, using gaming to interrogate “action, inaction and relation”.

Danielle doesn’t envision a dream-like or fantasy-inspired utopia, but stability and sustainability. She hopes for a broader definition of what transness means and opposes complacency in understanding the nuances in identity. “Because language of transness and nonbinary has hit the mainstream, I worry that it will suddenly become gendered as gender has, coming from a mainstream media push of understanding what we are,” she says.

For Danielle, it is imperative to “generate our own online and real–life real estate, building archives, places to visit that are run [by], centred [on] and paying Black trans people”. Through this, a continual conversation of what it means to be Black and trans can evolve without corporate interest. She explains: “The closer I get to myself, the further I get from the language of transness. In ten years, what serves me now I might find limiting and small, and I’m open to that possibility.”

She admits the difficulties in discovering the best way to archive Black trans people and their experiences, yet believes that “just that trying is one of the best things”. For Danielle, when only finding remnants of Black transness in histories, with no explicit description or exploration, the journey of archiving and the future is curious and ever-evolving.

This story is from our 2022 print issue, UTOPIA / DYSTOPIA — order your copy here.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.