What would it look like if we put people before cars?

'The big smoke’ is threatening our lungs and lives. Here’s the case for car-free cities.

Hirra Khan Adeogun

03 Mar 2023

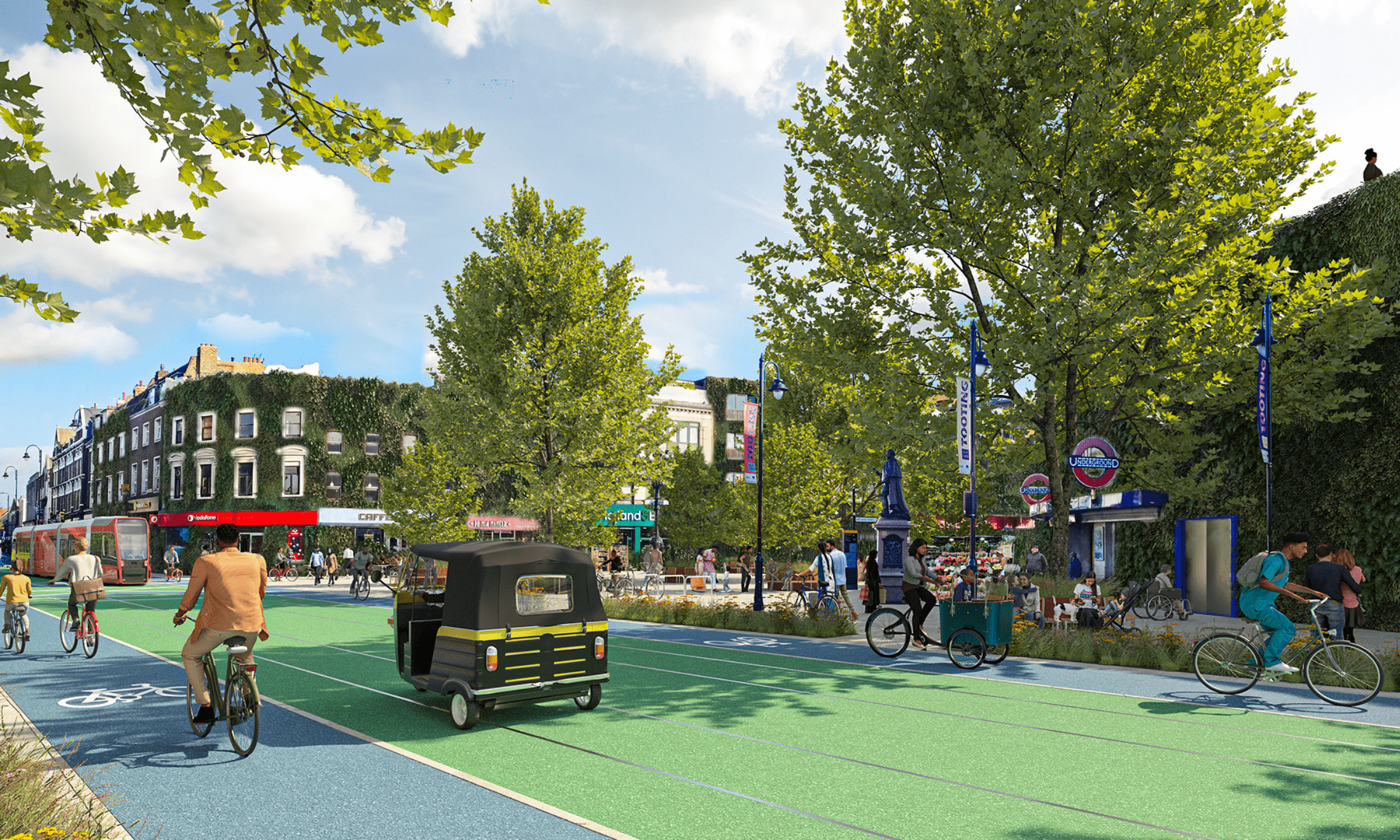

co-produced visions of a Car Free Tooting, via Possible

I have lived my whole life in London. University was the first time I met people who moved from British towns and villages to what they called ‘the big smoke’. Originating in the 19th century, the term characterises the period when coal-burning left London enveloped in thick smoke. It had damning classist connotations as the name originates from rural visitors to the city, visitors that tended to be wealthier, and could escape to the country for cleaner air while poorer people had no choice but to stay and work in the factories that fuelled the nation and the empire.

Despite being transformed by deindustrialisation long ago, London is still considered ‘the big smoke’. That’s now thanks to decades of policies that have catered completely to the needs and whims of cars – for example, fuel duty has been frozen since 2011 despite annual increases to public transport, and councils significantly subsidise parking spaces deterring people from using public land for sustainable alternatives. As we freefall towards climate collapse, society at large – including politicians, businesses, media and academia – has normalised car ownership, lethal toxic air and collisions, and we have made walking, wheeling, and cycling harder. Although less visible than in the 19th century, a dense cloud of pollution still hangs over us, disproportionately harming ethnic minorities and the most vulnerable.

It’s time to create car free cities that are free from the dangers, pollution and emissions caused by mass private car ownership. That’s not the same as a city with no cars at all; but fewer cars on the road means more space for those who have no alternative but to drive, and better cities for people and the planet.

“Whether it’s pollution or collisions, it’s people of colour and people in poverty who pay the price”

The case for car free cities is clear. 36,000 people die in the UK each year due to toxic air, but communities of colour are three times more likely to live in areas with very high air pollution, rendering them more at risk of serious health concerns, such as heart attacks, cancer and strokes. It is now a decade since the death of nine-year old Ella Kissi-Debrah, the first person to have air pollution listed as a cause of death; and her mother is still fighting for Ella’s Law, the Clean Air (Human Rights) Bill, to be introduced. We also know that people from deprived areas are more likely to be casualties in crashes and a person of colour in a deprived area in Britain is 25% more likely to be killed or injured as a pedestrian than a white person. Whether it’s pollution or collisions, it’s people of colour and people in poverty who pay the price.

The British government also estimates that the ‘social cost’ of noise pollution totals somewhere between £7 billion and £10 billion every year, but if you live in more socially disadvantaged areas you’re more likely to be impacted. Disabled people have their mobility constrained by high traffic and a lack of well-maintained and open pedestrian space and residential streets with high traffic have been shown to cut our social ties, divide communities and limit the ability to forge bonds with your neighbours.

A prime example of this is the M32 which cuts streets in two and severs communities in both Easton and St Pauls – one of Bristol’s most ethnically diverse and deprived areas. Another example closer to my home is Aberfeldy Estate in Tower Hamlets – again one of the most ethnically diverse and deprived areas in the country – which is blocked in by the A12, the A13 and the Aspen Way six-lane motorway. These are areas where car ownership is low, but the effects of car dominance are felt most violently. Clearly then, this isn’t just a car problem, it’s an equity problem. And that equity problem is fuelling the climate crisis.

Transportation accounts for one fifth of global emissions and private cars account for 45.1% of all transportation’s emissions. In order to reduce those emissions, it’s not enough to replace all of our fossil-fueled cars with electric ones. Electric vehicles (EVs) still produce considerable emissions in their production; and according to the World Health Organisation, air pollution-related deaths are most closely linked to particulate matter (the particles from brake, tyre and road surface wear that all vehicles produce, including EVs). We simply need to reduce the number of cars on our roads.

“In order to reduce those emissions, it’s not enough to replace all of our fossil-fueled cars with electric ones”

The good news is that freeing people from the burdens of car ownership is a major win – from boosting economic productivity to improving health outcomes to increasing community cohesion. And in recent years there is cause for hope. In London, the combined efforts of the Mayor and local councils to drive down car use through policies like expanding the ULEZ and using the revenue to invest in buses, prioritising active travel, pedestrianising streets and introducing low-traffic neighbourhoods, the capital is moving to become a happier, healthier and greener place to live as well as an asset in the fight against the climate crisis.

Measures like these are also spreading across the country. Clean air zones are now in effect in Birmingham, Bristol and Bath, low-traffic neighbourhoods are gaining traction in cities like Oxford and Bristol, and plans to make Birmingham “a super-sized low traffic neighbourhood”, and traffic reduction is catching the eye of councillors everywhere.

Opponents of change often use taxi drivers to mischaracterise calls for urban traffic reduction as class warfare. But this betrays their comfortability with the status quo in which predominantly migrant men of colour continue to work incredibly long hours for below minimum wage and very little respect. Professional drivers deserve so much more. In a climate-safe future where cities have very low car ownership rates, appetite for professional drivers will only increase. The profession can become a highly-valued and in-demand skill, with a secure and respectable wage, sick pay, pensions and annual leave. With less private cars on the road, drivers could turn jobs around quicker and earn more too.

“Cities liberated from car dominance are a crucial part of addressing the climate crisis”

Let’s not forget that the burden of cars isn’t the only thing falling predominantly on people of colour and deprived communities – the climate crisis is as well. Given our historic responsibility, our leaders have a duty to reduce our emissions. But we also need to stop exporting car culture around the world and, instead, emphasise the benefits of car-free living.

Cities liberated from car dominance are a crucial part of addressing the climate crisis while also creating a greener, more equitable place to live. A place where communities of all kinds can interact, where we can enjoy more green space, and we can get around easily via walking, wheeling or public transport. A place where all the amenities, businesses and services a person might need are only a 15-minute journey away. Where the air we breathe is clean, and there are far fewer vehicle collisions. A place where disabled people can travel more easily, where noise pollution is reduced, and no matter where you live, communities can be healthier and freer.

We need change now. ‘The big smoke’ can’t keep smouldering. We need to face up to the harms of car dominance, and work together to reduce pollution and emissions, making our cities cleaner, greener, safer, and happier for all.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?