How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

The last few years have seen progressive wins for Pakistan's transgender community. But rising prejudice and danger in recent months are forcing some to rethink their futures.

Ayesha Le Breton

21 Mar 2023

Shahzadi Rai, Aradhiya Khan and Hina Baloch

Content warning: mentions of violence, transphobia.

Khwaja Sira activist and community leader Shahzadi Rai is frustrated. It’s midnight on 1 February, and she’s just spent her evening fighting for the survival of Scrap Fest – a music festival highlighting trans and underground performers in Karachi, Pakistan. It was originally scheduled for that upcoming weekend, but encountered delays following nationwide backlash and a petition to the Sindh High Court (SHC), who ultimately suspended permission to hold ScrapFest at the city’s Clifton Park. Nonetheless, Rai and her fellow organisers refused to be silenced, and shifted the event online.

Ahead of the festival, Rai was informed by the Sindh police that the Pakistani Taliban threatened to destroy the event and harm members of the trans community. Netizens also stoked further hatred and dubbed the show as “homosexual”. The hashtags “#banscrapfest” and “#say_no_to_LGBTQ” trended on Twitter. These labels are anything but harmless in Pakistan where homosexuality is criminalised and carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.

“Recent years have seen some progress towards the inclusion of trans people in Pakistan, but warped perceptions toward gender, masculinity and morality are pervasive”

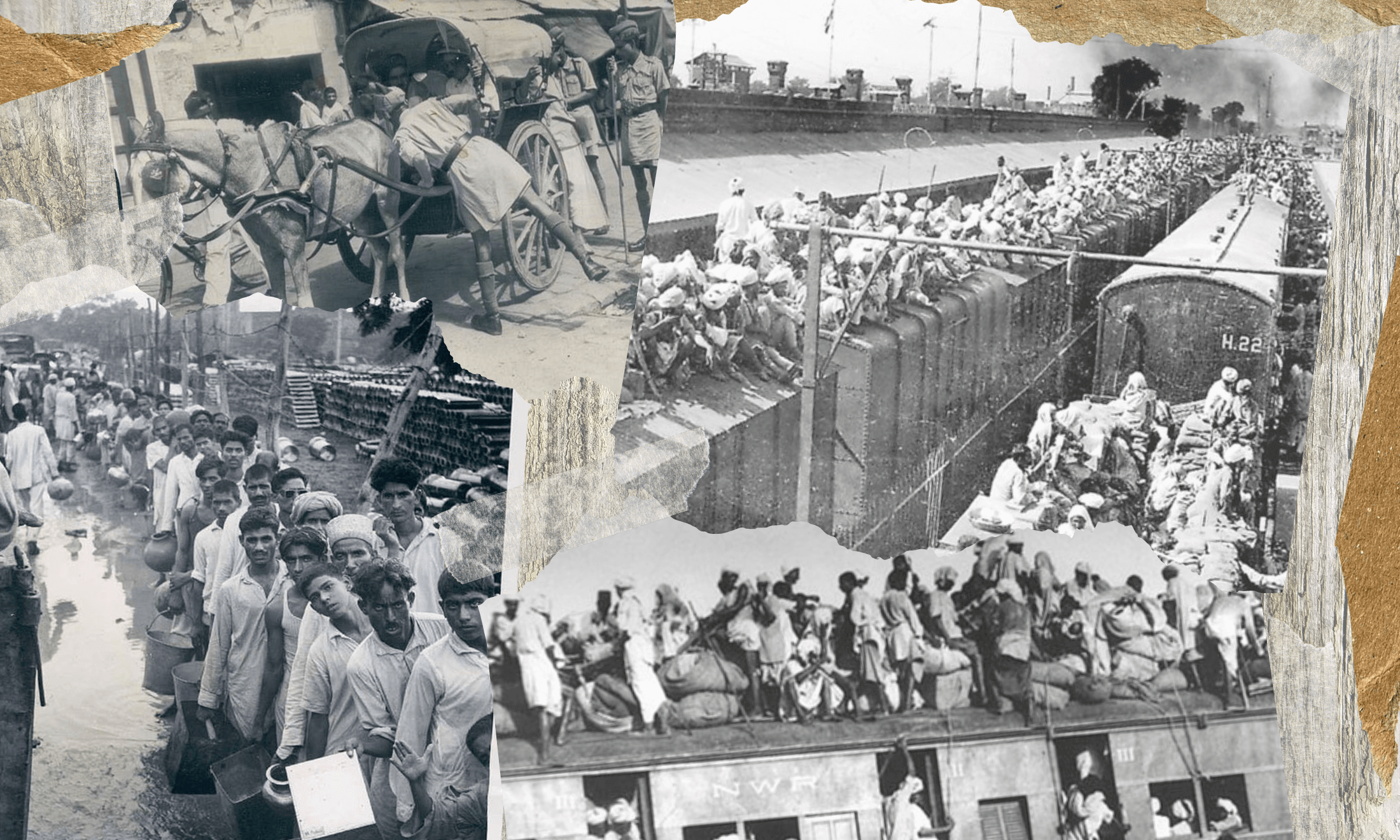

In Pakistan, the Khwaja Sira is an overarching term for transgender, non-binary and gender non-conforming people. Historically, they were considered sacred as guardians of religious sites, and held high advisory and leadership roles in the Mughal Empire. This shifted under British colonial rule in 1871, which arrived with the western notion of gender binaries and hetero-patriarchy, leading to the eventual criminalisation of Khwaja Siras, homosexuals, and wearing ‘feminine’ clothing. Recent years have seen some progress towards the inclusion of trans people in Pakistan, but warped perceptions toward gender, masculinity and morality are pervasive.

Four years ago, with the enactment of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2018, Pakistan became one of the first nations to legally recognize transgender people. In theory, the law allows equal rights to education, basic health facilities, writing their transgender identity on their identity cards and passports, besides the right to vote and contest elections.

Yet, while this legislation was a major step forward for a group which makes up more than 300,000 people in the country, it doesn’t necessarily erase prejudice, nor does it ensure safety. Now, there’s been a fresh assault on the rights of transgender people in Pakistan, with efforts to repeal or amend the bill escalating rapidly in recent months.

“Now, there’s been a fresh assault on the rights of transgender people in Pakistan, with efforts to repeal or amend the bill escalating rapidly in recent months”

Throughout September, a fresh set of petitions were filed against the landmark bill by leaders of the country’s largest conservative religious party, Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and were brought to the nation’s constitutional court where laws can be challenged on the basis of Sharia (Islamic law). On February 17, the Senate Standing Committee on Human Rights held a meeting to discuss these proposed amendments – the results signified major setbacks for the trans population.

“They weaponized religion against the most spiritual or marginalised community in the country,” says Hina Baloch, a fellow trans activist who considers Rai her ‘trans mother.’ JI’s recent political moves galvanised existing transphobia within Pakistani society, increasing the threat of violence against the vulnerable community. These moves have real world, dangerous consequences – according to trans community leaders, so far this year, they know of at least four trans people who have been killed in Pakistan.

Threat of violence

Global data collected by the Trans Murder Monitoring project reported that 14 trans people were murdered in 2022 in Pakistan – a higher figure than the previous five years, although the true death toll is likely higher due to underreporting. Amid this ongoing violence, leading members of the community, like Rai, are spearheading the fight for systematic and social reform. Through her roles as violence case manager at trans rights organisation, Gender Interactive Alliance (GIA), and with the Sindh Police, she streamlines communications between the trans community and authorities to report transphobic hate crime.

While Rai, now 33, has been volunteering with the Sindh Police for four years, she does not see it as sustainable. “We have to empower all police stations of the province so that they could directly take the cases of victims from the community,” she says. Whilst she describes the officers as cooperative, her efforts to implement long-term solutions within the Sindh police force, including policy around gender sensitivity and awareness, have been met with resistance. According to Rai, officers would prefer she maintain her role, rather than assume the responsibility of supporting the community themselves.

Rai has faced transphobic harassment first-hand, after a video of her went viral in which she addressed a JI audience with the plight of the Khwaja Sira and trans community. “Jamaat-e-Islam targeted me, they even came to my home twice,” she says. “They stopped me in my park, where I’ve walked for the last 10 years and they harassed me, they even hung posters in the park.” Rai recalls how the posters outlined transphobic messages, stating that to be transgender is to be at open war with the Quran and the religion of Islam. This is a painful accusation given the context that blasphemy is punishable by death in Pakistan.

“They stopped me in my park, where I’ve walked for the last 10 years and they harassed me, they even hung posters in the park”

Shahzadi Rai

Baloch was also targeted. On 20 November last year – International Transgender Day of Remembrance — she helped organise the Sindh Moorat March, Pakistan’s first trans pride. Threats of violence ensued. “After the Moorat March we received rape threats, acid attack threats, we started receiving letters,” she says. “Mobs tried to attack us, we escaped vigilantes, there were people following us to our homes, to work.” Fearing for her safety, the 30-year-old trans woman and a number of fellow organisers relocated to Lahore for 10 days. Baloch’s eventual return to Karachi exposed a harsh reality. “We’re just preparing our minds and ourselves that something bad can happen any day and we can’t hide, right? We just need to keep going and keep working.”

‘They are on their way to roll back rights given to us’

There’s broader issues of social and economic exclusion too, even though the Trans Act was enacted almost five years ago. For those who have access to schooling, employment prospects remain few and far between. According to a Ministry of Human Rights report in November 2022, data from 36 ministries showed that the Act’s job quota had not been followed. Within this context, some members of the trans and Khwaja Sira community have no other choice than to earn a living through begging, dancing and sex work, leaving them vulnerable to violence and exploitation.

Last year, provincial governments took steps to increase educational opportunities for the trans community. Across Punjab, four schools were opened for trans students. In April 2022, Sindh’s education department announced plans for a policy that aims to give the community equal access to education and include transgender identity in the academic curriculum. And on 29 January this year, trans people were declared eligible to receive cash assistance for the first time under the government’s Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) which was launched more than 10 years ago. Rai hosted the launching ceremony.

24-year-old trans activist Aradhiya Khan spent a year and a half working with the Akhuwat Foundation, where she introduced a non-governmental Khwaja Sira support program in Sindh. “I think that this is one of the closest things to my heart,” she says. “The program primarily used to cater to transgender who were 14 [years old] and above, who were earning Rs10,000 [per month] and less and who were living in underprivileged areas and who needed stipends in healthcare and medical facilities.” The young organiser has also led gender sensitivity workshops and trainings in schools and corporate environments, hoping to debunk myths and misconceptions attached to her gender identity.

“There is no progress. In fact, things are getting worse”

Hina Baloch

Small strides towards a more equal society were made on the provincial level and by the community, but Baloch believes the bigger picture is bleak. “I think that if we talk about the progress on the federal level, there is no progress. In fact, things are getting worse,” she says.

In last month’s Senate Committee on Human Rights meeting, the chairman, Senator Walid Iqbal argued that under Islamic law gender can only be determined from physical and genital attributes. “They are on their way to roll back rights given to us,” says Baloch. The word transgender will also be removed from the bill, replaced with khunsa (intersex) and a medical board will determine the status of the khunsa person. Once enacted, these changes will threaten the statehood of many Khwaja Siras or trans persons. This arrives after months of misinformation campaigns, peddled by conservative parties and influencers.

Censorship and cyber harassment

Still today, influential figures with social and monetary capital are spreading transphobic hate across Instagram and Twitter. Their efforts have spiralled into an onslaught of cyber-harassment, censorship and intolerance.

In October 2022, a complaint by a religious party leader prompted the Pakistani government to ban the critically-acclaimed film Joyland. The film portrays a love affair between a cis-gender man and a trans woman. JI party member, Senator Mushtaq Ahmad praised the embargo in a tweet, as did prominent fashion designer Maria B who often shares ill-informed opinions about the trans community in the name of Islam. Amidst the controversy, #ReleaseJoyland and #BanJoyland trended on Twitter. Although the federal ban was eventually lifted, currently Punjab province – which accounts for an estimated 64.4 % of the country’s transgender population – is not screening Joyland.

The furore over the film is just one example of how social media campaigns are targeting trans people. “There have been profiles made on Instagram or Twitter that have been attacking specific transgender activists,” says Hyra Basit, from The Digital Rights Foundation (DRF), a feminist non-governmental organisation that focuses on protecting women’s rights in digital spaces. Overtaking previous years, the organisation’s Cyber Harassment Helpline, managed by Basit, experienced a rise in cases from trans individuals, counting 19 related reports by the end of 2022. She directly attributes this to the JI-led “hate campaign”. Basit describes some of the perpetrators as “doing everything to dehumanise their targets”.

“There have been profiles made on Instagram or Twitter that have been attacking specific transgender activists”

Hyra Basit

The helpline’s services are threefold including legal support, digital security literacy, and counselling. According to Basit, the trans folks who approach DRF tend to opt out of filing legal complaints. “For their own reasons, which might include hesitancy to face those legal officers, or FIA [Federal Investigative Agency Officers] or they aren’t confident it would actually lead somewhere.” With particularly vulnerable minorities, like members of the trans community, DRF prioritises digital solutions.

“We give them higher priority,” says Basit. “We reach out to social media companies or websites wherever there’s content that might be hurting them in any way or harassing them.” She says that the response from tech companies to transphobic hate speech on their platforms has been varied, and in some case, ineffective.

Battling censorship, online harassment, violence and systemic erasure, organisations and members of the trans community across Pakistan are tirelessly campaigning for their equality. But this comes at a heavy personal cost. For activist Khan, the onslaught of this misinformation and hate is her reality. “I have certainly felt changes in my friendship with a lot of people. A lot of people have been very trans supportive. But they have made very clear statements and choices for not supporting the spectrum of the LGBT [Q+] community.”

While Khan is proud of her work in contributing to the movement and to amplifying trans rights, she’s realistic about what the future might hold. “I have lost hope for this country,” she says. “I would be very happy to just go out of this country, for my own sake, my own well being, my own life.”

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.