Wikimedia Commons / Canva

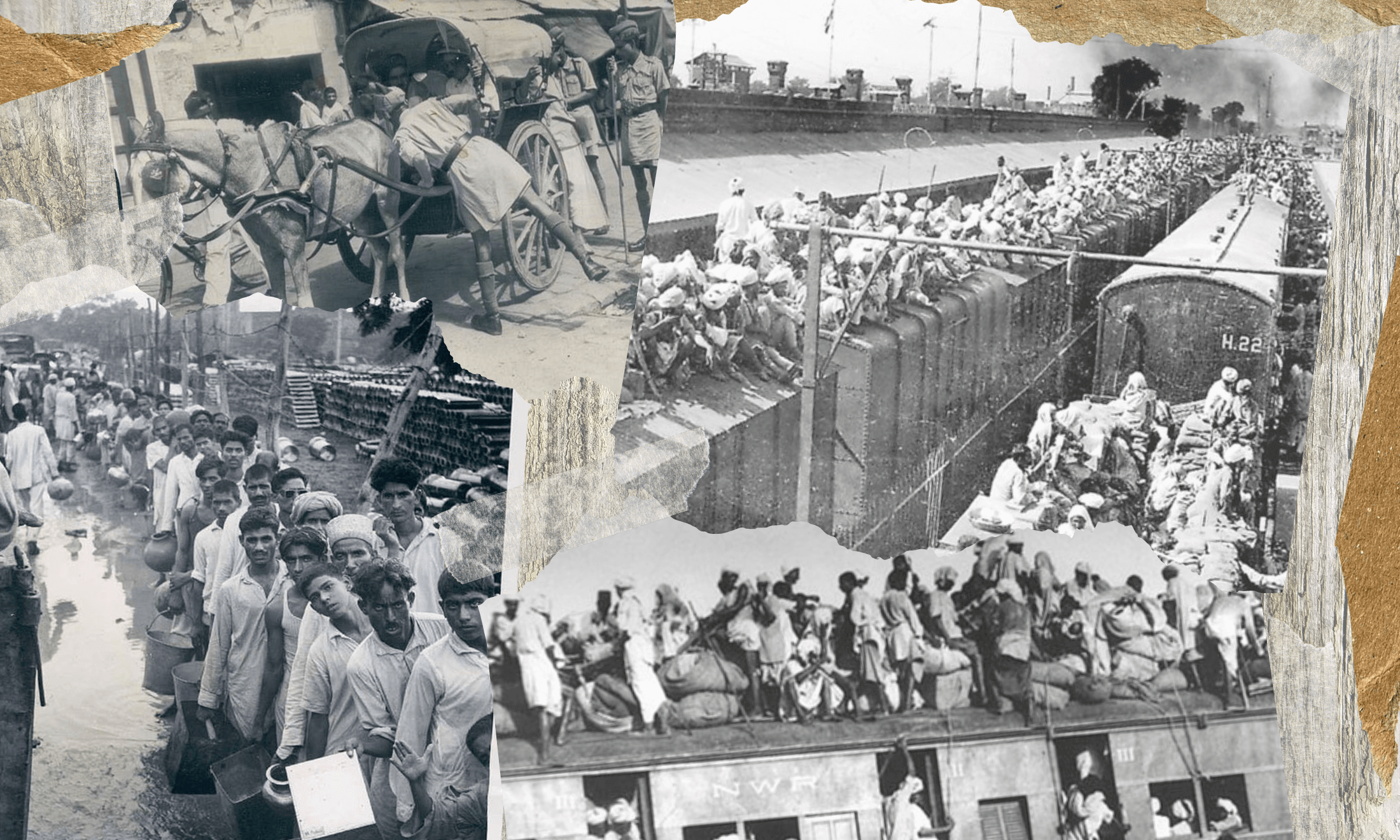

‘The other side’: Remembering Partition 75 years on

In this extract from her book Remnants of a Partition, Aanchal Malhotra explores borders, family and visiting Lahore.

Aanchal Malhotra

15 Aug 2022

I have grown up listening to my grandparents’ stories about ‘the other side’ of the border. But, as a child, this other side didn’t quite register as Pakistan, or not-India, but rather as some mythic land devoid of geographic borders, ethnicity and nationality.

In fact, through their stories, I imagined it as a land with mango orchards, joint families, village settlements, endless lengths of ancestral fields extending into the horizon, and quaint local bazaars teeming with excitement on festive days. As a result, the history of my grandparents’ early lives in what later became Pakistan essentially came across as a very idyllic, somewhat rural, version of happiness.

Many a time, I’d imagine what my life would have been like had I too been born and raised on ‘the other side’, for, in these seemingly superficial tales of the past, the words ‘religion’, ‘faith’ and ‘Partition’ were never mentioned. My paternal grandfather, my dada, hailed from Malakwal, a small town in the Mandi Bahauddin district of Punjab about 250 km from Lahore, and my dadi from Muryali, Dera Ismail Khan, in NWFP.

Both my maternal grandparents, my nana and nani, came from Lahore. The syncretic feeling that each of their families harboured for land and community was drastically altered by the events of the Independence and Partition of India in 1947. And, what’s more, the journeys of migration that they and many other families were forced to undertake covered their existence in a shroud of painful silence that only magnified as the years went by.

‘An unholy rush’ was how the award-winning Punjabi poet Prabhjot Kaur described this massive exercise in human misery. Having been displaced in the communal riots herself, she penned heartbreaking, soulful verses recounting an event that is considered one of the largest mass migrations of people in world history, leaving up to one million dead and forcing approximately 14 million to flee in both directions across a newly created border.

‘How could Indians – Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, but Indians all the same – be suddenly drawn apart for their differences, despite being children of the same soil?’

So how did it happen, I wonder to myself, as the third generation of a family affected by the Partition. How was it that the division of a land was so easily conceptualised? Was it really possible to carve out a new country from within India, consolidating most of the Muslims living across the expanse of the subcontinent into one nation? How could Indians – Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, but Indians all the same – be suddenly drawn apart for their differences, despite being children of the same soil?

At the historic Lahore Conference of the Muslim League in March 1940, the future Pakistani governor-general Muhammad Ali Jinnah listed the inherent ‘differences’ between the two peoples as the basis of the demand for the country of Pakistan:

“We are a nation with our distinctive culture and civilization, language and literature, names and nomenclature, sense of values and proportions, legal laws and moral codes, customs and calendar, history and traditions, aptitude and ambitions. In short, we have our own distinct outlook on life and of life. By all canons of international law, we are a nation.”

Taking me back to his teen years in pre-Partition Lahore, Pran Nevile – former diplomat, art historian, and author of several books including Lahore: A Sentimental Journey – recalled for me the amity and brotherhood he had witnessed between the people of various communities. ‘When Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs broke sugarcane, or ate aloo-puri, they did so in the same fashion. When they went to buy wares at Anarkali bazaar, they did so together. This was – is – our shared Punjabi culture and it had little to do with religion.’

In stark contrast, my grandmother Bhag Malhotra recalled walking to school in NWFP in the early months of 1947 and being called a kafir (a disbeliever) all the way, despite having lived there her whole life. Amir Ahmed, a resident of Nawabganj, Delhi, was eleven years old at the time of Partition, and his family had decided not to migrate. ‘Partition,’ he claims, based on the sights of Delhi at that time, ‘had brought out the ugliest, most vehement side of humanity, showed us what the word insanity truly meant.’

‘Were our land, our languages, our food, our habits, really as dissimilar as some had declared them to be?’

How, I wondered, did families who had lived for generations on the same soil suddenly find themselves on the ‘wrong’ side of the border? How, having celebrated both Diwali and Eid, eaten sugarcane and aloo-puri with people of all religions, did they suddenly become ‘the other’? Were our land, our languages, our food, our habits, really as dissimilar as some had declared them to be?

During my time in Pakistan researching [my] book, Lahore embedded itself into the same place in my heart otherwise occupied by my hometown of Delhi. There was no sense of homesickness or unfamiliarity. On the contrary, its streets seemed to be alive with the same history as the streets of Delhi; its monuments boasted of the same civilisations; and its government buildings and old bazaars structurally felt the same. And what had I been expecting, really, if not just that? I didn’t stand out as someone from across the border, apart from the fact that I spoke more Hindi than Urdu. But in terms of physicality, I was folded seamlessly into the public landscape by the skin tone, angular jawline and pronounced chin I had inherited from my great-grandmother from the Frontier; I became like every other woman walking the streets of urban Lahore.

Remnants of Partition: 21 Objects from a Continent Divided by Aanchal Malhotra is published by Hurst Publishers and is out now.

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

The Gulabi Gang is a sisterhood fighting against domestic violence in India

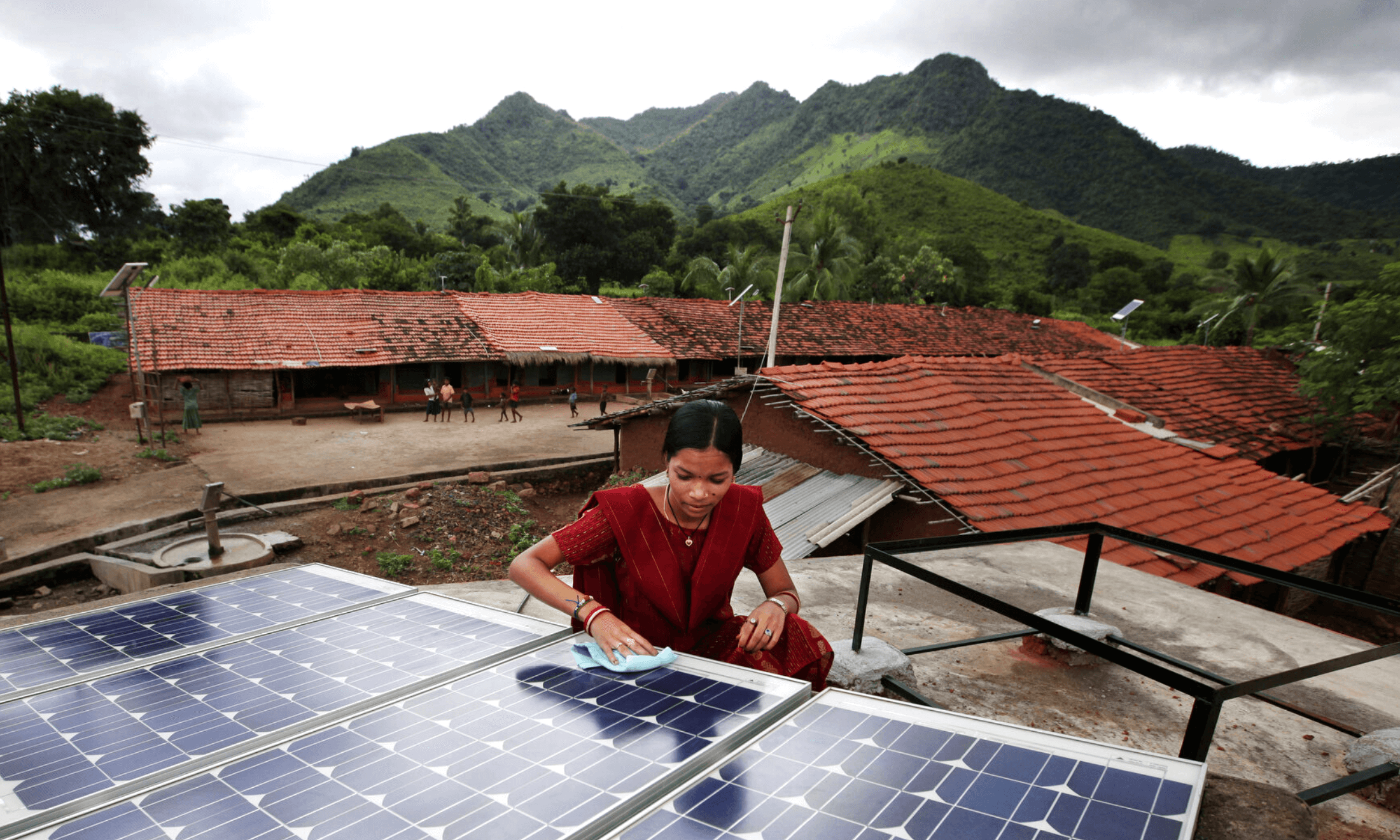

After a gruelling year of heatwaves and floods, Indian climate groups get to work