‘The world opened up’: inside Britain’s secret history of queer South Asian parties

In the late 1980s and 1990s, queer British South Asians who found gay clubs too white and mainstream Bhangra events too heterosexual created their own spaces

Safi Bugel

25 Feb 2021

Ejel Khan, a coordinator of the Muslim LGBT network, was just 14 when he started attending house parties for queer South Asian folk in his hometown, Luton. Still clad in his school uniform, he’d stay for a couple of hours in the afternoon with his newfound “friends, lovers and comrades” before returning home for dinner with his conservative Muslim parents, citing a visit to a classmate’s house as reason for his absence.

Finding gay clubs too white and the mainstream Bhangra daytime parties too heterosexual, young queer people of South Asian descent created their own social spaces in late 1980s and 1990s Britain. Friends’ living rooms, strangers’ houses and later events like Club Kali allowed these adolescents to find solace, strength and a sense of self whilst homophobia and racism continued to flourish around them.

Much like the public daytimers, Ejel’s house parties were accompanied by the sounds of the time: Bhangra and ‘Bollywood fusion’, as well as ragga, reggae and hip-hop. However, unlike those settings, the house parties were smaller, more personal affairs, frequented by figures who were at the fringes of society. Attending were gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people, sex workers and drug addicts.

“Luton was quite a polarised town,” Ejel explains, referencing its ongoing reputation as a hotbed for racism. Though he was underage for the bulk of his house party years, the disposition of nightlife was known. “We didn’t have any Asian nights, and the gay bars at the time weren’t really welcoming of South Asian people. They didn’t reflect our experiences, our music.” This regional hostility took place against a backdrop of rampant and widespread stigma around HIV and AIDS, as well as institutional homophobia: Section 28 was in place and gatherings of LGBTQI+ people were subject to police raids. Within this context, private house parties formed an important space for local queer people to be themselves, sincerely and safely. “We were a subculture,” Ejel says.

Swapping his school shirt and tie for his Sunday best (“a nice t-shirt and jeans, nothing too flamboyant”), Ejel’s social life continued to centre around these houses in his later teenage years. Despite then having the ID and the networks to access the hitherto forbidden club spaces, Ejel still felt wary of them. He preferred the close-knit nature of the private functions, which took place in daylight and tended not to exceed ten people. “You could get lost in the club,” he recalls. “It’s dark, you’ve got the music banging away and you’ve had a couple of drinks. In a house party, it’s much more intimate. You get to know people.”

Throughout his adult life on the campaign circuit, Ejel has learned that congregating in houses was a shared experience for young LGBTQI+ South Asian people across the country. Indeed, Rajinder Dudrah, Professor of Cultural Studies and Creative Industries at Birmingham City University, holds similar memories of mingling in friends’ living rooms during his university years in Portsmouth. Whilst Ejel’s experiences were characterised by taking shirts off, having photos taken and other “hijinks”, Rajinder’s were more sedate in nature. For him, these get-togethers were an opportunity to explore both queer and South Asian culture beyond sex and sexuality, namely through literature, personal tales and music. Here, Rajinder’s friends discussed the works of James Baldwin and other LGBTQI+ writers, as well as the lived experiences of their older queer counterparts, over cups of tea. Furthermore, the mix of pop hits, “homegrown British Bhangra” and Bollywood from India was a way for him and his peers to explore their identity and heritage. “It was part of who we were as international beings living in big cities.”

“It’s dark, you’ve got the music banging away and you’ve had a couple of drinks. In a house party, it’s much more intimate”

These avenues for exploration and learning from queer “siblings” constituted an alternative family dynamic, wherein Rajinder could interact with people like himself, as well as other members of the community. “The world opened up. There was a vista, a diversity, a range beyond just being gay or lesbian. And then it was almost like technicolour happened in front of you; you saw the world through colour and through different personalities and people,” he recalls. “So it was partly you seeing yourself – that important moment of representation – but actually seeing diverse representation in others as well.”

In this sense, Rajinder considers the get-togethers as a “haven” for young people of South Asian origin who deviated from traditional expectations of them. “They were safe spaces. They were spaces of growing up, of gathering experiences and knowledge, and of experimentation as well, trying out new things,” he reflects.

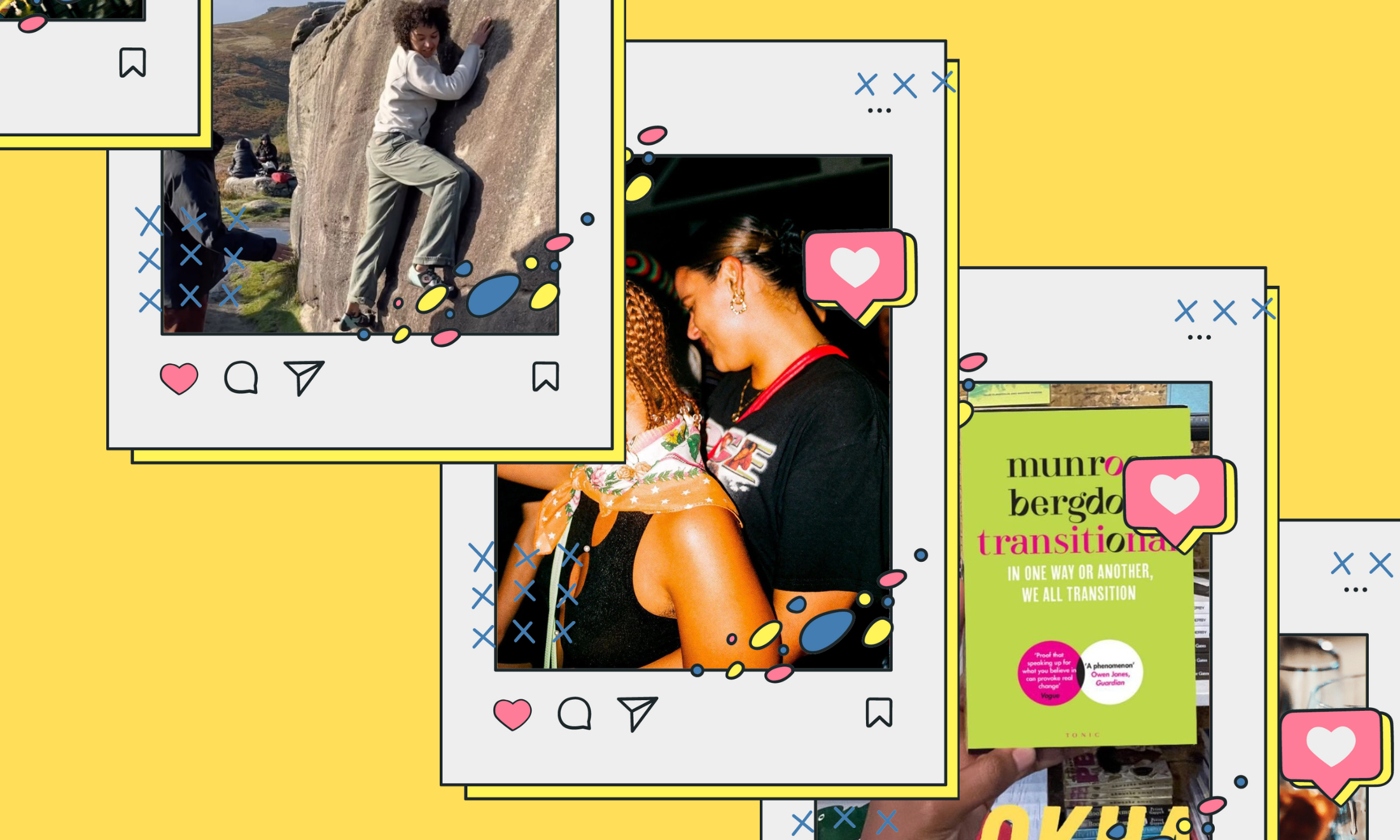

Like Ejel and Rajinder, London-based activist Sabrina Qureshi also came of age at the turn of the decade, coinciding with this culture of queer gatherings within the home. As a young British Asian lesbian, she found comfort and companionship at ‘blues’ – events run in the houses of women of Caribbean and African descent, cleared out and opened up for the occasion. She recalls food and drinks being served as people danced, with entry on a pay-as-you-feel basis. The impact of these functions has been lasting for Sabrina and her peers. “It was more of a movement than just a house party,” she says. “It meant that women formed relationships and knew each other.” Indeed, she still treasures friendships made within these spaces 30 years on. “It was empowering seeing all these strong women around.”

As she got older, Sabrina attended larger queer South Asian events such as Club Kali, Club Asia and Shakti. Set up in 1995 and still in existence today, Club Kali was created to uphold the safe community spirit of the house parties but in a public venue with DJs, lights and drag queens. Like the blues, the space was shared with their Black counterparts, whilst reggae and ragga complemented classic sounds from the Indian subcontinent. “I wasn’t really brought up with Bhangra or Asian music,” Sabrina says. “But when you get estranged from your own culture once you’ve come out as gay, just hearing Hindi or Urdu in the songs… it was lovely.”

Seeing people wearing saris and shalwar kameez in a club setting without being exoticised or held to gender standards was “affirming” for Sabrina: it was a space where you could “just be”. This sentiment is echoed by Rajinder, who also regularly attended nights like Club Kali in his twenties: “they were our spaces. They were safe, we didn’t have to writhe for our music to be played and we didn’t have to worry about racism. There was also the idea of being able to have that club space, the whole club space… it wasn’t like you were a fringe or just an hour getaway slot, it was your space and it was a space that was shaped by the community.” These events still exist, but many operate on new terms: the explosion of Bollywood in the early 2000s meant that the dancefloors have since attracted increasing numbers of white “tourists”, whilst newer nights like Hungama retain their South Asian music focus but are open to all.

Though the nature and frequency of these parties have shifted, they were formative for a generation of young people who occupied a liminal position between gay and South Asian circles. Alongside the house gatherings, these tailor-made spaces fostered self-expression and forged connections between members of the community. And the impact of them continues to resonate, as Sabrina’s lasting friendships, Rajinder’s academic research and Ejel’s subsequent activism show. “It all goes back to those years,” Ejel says of the era he partied in. “The people I met are unfortunately no longer with us, but they will live on. That’s why I do what I do, in their memory. They were people who didn’t have a voice.”