The director of ‘Amazing Grace’ remortgaged his house so you could see this lost Aretha Franklin performance

Amahla

17 May 2019

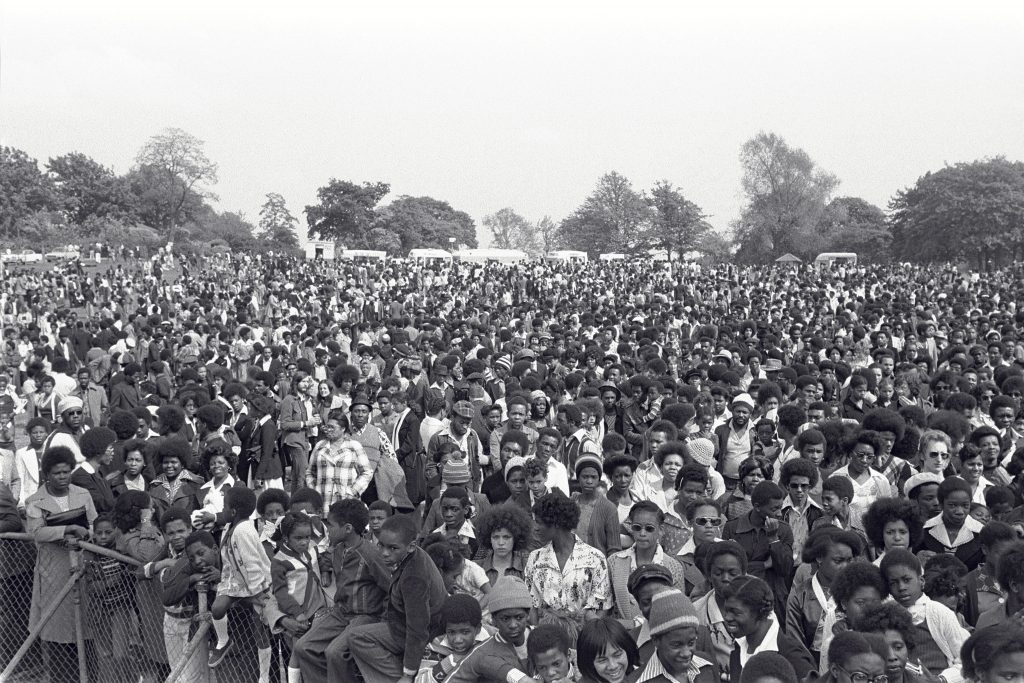

It’s 1972 in the south of Los Angeles and there’s a feeling of anticipation inside the New Temple Baptist Church. Standing beside gospel icons Clara Ward of The Ward Singers, her father C.L Franklin a baptist minister and civil rights activist, and Reverend James Cleveland a gospel music pioneer, a young Aretha Franklin steps up to the podium. With one note the room is arrested by her powerful vocals. Backed by three instrumentalists and The Southern California Community Choir, Aretha’s voice rises and pierces from one side of the space to the other, taking the audience in the church and theatre with her. As the reverend aptly puts it to the crowd: “She can sing anything – anything”.

This scene is just one from the newly released Amazing Grace, a film that demonstrates the immeasurable talent of the late soul singer, who died in August 2018. The 87-minute movie documents the recording of Aretha’s seminal album of the same name, giving us unprecedented insight into how she built her legendary status as The Queen of Soul. The song and namesake of the film would eventually go on to sell over two million copies in the United States alone, whereas she would go on to even greater stardom, selling over 75 million records worldwide. Despite shifting huge numbers, in these scenes, you glimpse how she maintained a close relationship with her community.

Initially set for a 1972 release, Amazing Grace was stalled by problems in production, release schedules and even Aretha herself. “She was probably most upset about the fact that in 1972 they thought they were going to make her into a movie star and she never got her chance,” Alan Elliot explains to gal-dem over the phone. Mistakes during filming meant the audio and footage were unable to be matched together and Aretha’s forthcoming entry into the film industry was stunted. Only a lucky combination of technological advances and Alan’s extreme persistence as the film’s director brought Amazing Grace to our screens. He actually remortgaged his house to deflate rising production costs. “No one else would do it, so I had to,” he says. But after 42 years of filmmaking, Amazing Grace continues to propel Aretha’s legacy of soul, social justice and unity.

In the early 70s, Aretha was already a huge star, but the musical landscape was changing. Atlantic Records was moving from being an R&B label to what Alan describes as “more of a rock and roll label with The Rolling Stones, The Jets. So the dynamic had changed”. This is true, one more album and Aretha would move to start a new chapter of her career with Clive Davis at Arista Records. Seen through this prism, in the recording of Amazing Grace Aretha not only shows command over her musical direction but an entrepreneurial spirit. She wanted to make a competitive double album in the same vein as Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma in 1969 or The Beatles with their White Album (1968).

However, true to the lyrics what was lost is now found thanks to Alan’s digging. “I first saw [the footage] in 2008. In 1990 I was a producer at Atlantic Records and found out about the movie because I worked with Jerry Wexler (who worked with the likes of Aretha Franklin, Dusty Springfield, Wilson Pickett) who produced the record,” he says. Aretha filled the New Testament church primarily with the local community. Churchgoers, children dancing alongside their parents and grandparents. One can only imagine the defeat Wexler would have felt – being unable to bring such a momentous moment to life on our screens. Alan sensed this immediately, acknowledging there was “a community” that could be drawn out from the record alone. Not least because it was originally written by an ex-slave trader who had seen the error of his ways. This, coupled with the narration of legendary composer Reverend Cleveland dovetailing Aretha’s songs, make for an exciting and riveting film.

Speaking on the stumbling blocks initially faced by Jerry, Alan says after years of trying that “no one had any energy towards getting it done”. You’d assume that such a long and complicated process would ultimately require a lot of collaboration. “No,” he reveals. “It was completely one guy sitting at the back of his house making a movie. That’s how it had to be, I’ve had lots of help along the way, my producing partners have been terrific. The editor was great. But, at the end of the day, it was my wife and I trying to figure out ways to get the movie out.”

Themes of community and family are set out from the very beginning of Amazing Grace. One shot that leaves an imprint in my mind is that of Aretha’s father C.L. Franklin wiping her forehead as she sits down to play the piano. Just as for us Amazing Grace is a historical work, it is also a document and heirloom for all those involved, particularly for the musicians who 46 years later see the product of their work. Of course, none of this could have gone ahead without the Franklin family, who Alan describes as “great partners”. “In terms of a legacy, they have an incredible responsibility that they’re dealing with”.

Another striking feature of Amazing Grace is its structure. Unlike most music documentaries there are no interviews, no cutaway scenes to leading African American scholars or musicians, there are no distractions. Aretha is the focus and the cast, crew and community all revolve around her in all her glory. Alan says: “I don’t like most music documentaries. So we sold the idea of musical theatre”. Musical Theatre always begins with an opening, introducing each of the characters. “Then you have an ‘I wish song’,” he says, which is a song that expresses hope for something better like ‘Wholy Holy’. Swiftly followed by “a big end of the first act show”. Here that is of course ‘Amazing Grace’. Then there’ll be what they call the 11 o’clock number “a showstopper” that occurs in the second half which is placed beautifully with ‘Never Grow Old’. It is this format that makes Amazing Grace so captivating.

“This was completely one guy sitting at the back of his house making a movie, that’s how it had to be”

Alan Elliott

With each song, Aretha transports you not just on an emotional journey but to 1972 Black America. For Alan, it was important to “never get out of the room” because in the room you are consumed entirely by the grandiosity and skill of Aretha’s voice. The room conceals the triumphs and tribulations of the time, only revealing itself through song – like the emotional ‘Mary Don’t You Weep’, a slave song from the civil war era.

By staying in the room, it’s easy to forget the context of 1972. That Shirley Chisholm was soon to announce her run for the Democratic presidential nomination, being the first major party African American candidate to do so. Or, that the country was still trying to move forward after a number of devastating losses Malcolm X (1965), Martin Luther King (1968) while simultaneously attempting to enact the legislative changes that were passed shortly after their deaths, Civil Rights Act (1964) Voting Rights Act and Loving v Virginia verdict that legalised mixed marriages (1965). All momentous symbolic change but ones that took longer for practical change to come into fruition. Change made in direct response to the black activism of the decades prior, in part aided by Aretha, her friends, peers and family.

In Amazing Grace, the shots are shaky and unstable but they give way to the movement of the room. Aretha herself barely utters three words, instead communicating through song. At one point she silences the room with a slight lift of her hand. Only groundbreaking artists are able to command a room so effortlessly, “She was not one to talk about things she was one to do about things. She was a big supporter of Martin Luther King, of African American causes particularly in Michigan and poor people’s campaign that her father helped built” says Alan.

A huge part of Aretha’s legacy was her ability to convey socially progressive messages in an accessible way. Just look at ‘RESPECT’, ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’. She used her soulful voice to further her political prowess, touring with changemakers like Martin Luther King and singing at the 2009 inauguration of the first black president of the United States, Barack Obama.

Amazing Grace is testament to the transformative power of music and the skill of those musicians lucky enough to steer it. Amazing Grace is not just a film about Aretha Franklin, it is about the community that hung on her every word. It is an archived piece of history. “Amazing Grace makes people aware there is a larger thing inside the feeling that she gives in the music,” says Alan. “Not just this titanic voice, but also a titanic spirit and the responsibility of what that spirit gave to us.”

Amazing Grace is in cinemas now