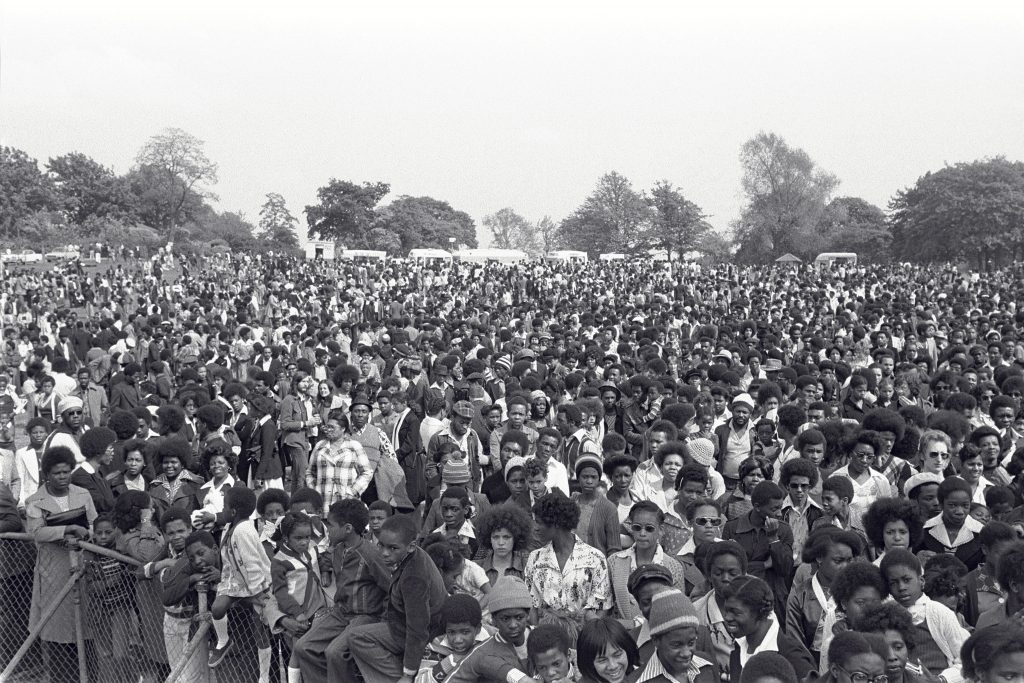

Photography by Neil Kenlock

Decades of UK anti-racist organising reminds us to prepare for the long fight ahead

Leah dives into the history of fighting, protesting and organising to dismantle the structures of racism and how it could help us tackle racism now.

Leah Cowan

05 Jun 2020

The road to revolution is long. As city streets across the world burn with rage and injustice, and voices join together to speak truth to power – we know that black lives have always mattered even if structures of racism and capitalism see us as disposable. We know that this fight is nothing new, and the slow path to progress is well-trod. Our struggle against white supremacy will continue long after the hashtags and the performative allyship fades away in the coming weeks; in knowing this we can find strength, and prepare to sustain each other for the journey ahead. However, there is a particular kind of heart-break the first time (and for many of us, recent events won’t even be close to the first time) we realise that the more things change, the more they seem to stay the same. When the hill ahead feels too big to possibly tackle and another mountain looms just behind it, can delving into the history of anti-racist organising in the UK give us any clues about a way through?

Next week, when white people and corporations alike are bored of publicising their meagre donations and conducting their self-serving check-ins, we will still continue to be black. Our chests will still be at risk of asphyxiation when the timeline returns to stunting and influencing as usual. Observing the consistent pattern of a particular injustice becoming high-profile, a period of (inconsistent) public outrage and then the return to normalcy for those not directly affected by racism can feel incredibly disillusioning. The pursuit of meaningful social change is often therefore experienced as a thankless commitment, and by definition an unremunerated grind — as Arundhati Roy writes in 2016: “Real resistance has real consequences. And no salary”.

“Anti-racist organising drives crucial wedges into the fortress of structural inequality”

However, anti-racist organising drives crucial wedges into the fortress of structural inequality. We can employ a diversity of tactics in order to achieve our objectives by any means necessary; we must learn from past victories and improve our organising by working from the margin to the centre, knowing that until trans, working-class, disabled, sex-worker, queer (and more) black people are free, we will all be unfree. It is not possible to burn ferociously in the face of every high-profile incident of racism; experiencing white aggression in its various forms every day already drains our energy. At the same time, tipping over into defeatism and cynicism that “nothing will ever change” means accepting, however reluctantly, the status quo which is killing us. To paraphrase Zora Neale Hurston, if we stay silent, they’ll kill us and say we enjoyed it. Instead of feeling defeated once the news cycle moves on, we can strategically plan for the fight ahead by learning lessons from anti-racist organising that has come before us. Heart-break is devastating and perspective-changing. Together we can evolve healed and equipped for the next encounter.

On the shoulders of organisers before us

Anti-racist movements in the UK are typically pinpointed as coalescing in the 1970s and 80s. This was an era when black and Asian communities came together, not in a perfect harmonious union, but in a united front of sorts while still wrangling with the same issues of sexism, ableism, colourism, homophobia and transphobia which continue to hinder social movements in big, big 2020. The 1970s arrived in the wake of Conservative shadow minister Enoch Powell’s racist ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech which warned that “In this country in 15 or 20 years’ time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man”.

This decade saw the rise of the far-right fascist party the National Front, the ramping up of stop and search of young black people (know as “sus laws”), the formation of the Asian Youth Movements, in part stoked by the racist murder of Gurdip Singh Chaggar in Southall in 1976, and the emergence of the Southall Monitoring Group in response to the murder by police of Blair Peach during a peaceful protest in 1979. Many other police Monitoring Groups also formed across London providing support to people affected by state violence. These groups provided community solidarity, defence against violence, and scrutiny of the racist state.

“20,000 people carried out a seventeen-mile, eight-hour march from Deptford to Hyde Park”

In 1978 the Organisation for Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD) was formed, beginning to campaign on issues including deportation, domestic violence, and policing. The Brixton Black Women’s Group also emerged, out of which sprung many other local Black women’s groups. These collectives included organisers such as Gail Lewis, Olive Morris, and Stella Dadzie. These groups joined the dots between sites of oppression such as racism and sexism, and showed how movements needed to connect and work together, not operate in silos. At this time the British Black Panthers were also operating, led by Obi Egbuna and later by Altheia Jones-LeCointe, who defended herself as one of the Mangrove Nine – a case in which nine activists were accused of inciting a riot during police targeting of a restaurant which was a hub for black community organising. These moments illustrate only fragments of a movement that was broad and internationalist in approach; for example, the Grunwick Strikes led by Jayaben Desai challenged racism, sexism, anti-immigrant attitudes and poverty wages at a film processing factory in Willesden, bringing together anti-racist and worker’s struggles.

In the decade that followed, the Hackney Community Defence Association (HCDA) was formed as a self-help group in response to the relentless killing of black men in police custody. In 1981, a racially-motivated arson attack on a house in New Cross killed thirteen people (and a further person who died of suicide two years later). In response, the Black People’s Day of Action was organised by the New Cross Massacre Action Committee, led by Darcus Howe (an activist and member of the British Black Panther Party) and John La Rose (a poet, campaigner and founder of New Beacon Books). On the day of action, 20,000 people carried out a seventeen-mile, eight-hour march from Deptford to Hyde Park, carrying thirteen banners for the dead and a coffin. This action set an important precedent, showing the power of black people coming out onto the streets to unite around a single tragedy which illuminated a wider issue.

This action – one of the most notable marches in British history – alongside widespread police brutality and rising unemployment due a global recession, sparked riots across the country, including in Brixton in London, and a few months later in Moss Side in Manchester and Toxteth in Liverpool. Research into the 1981 riots commissioned by the government – the Scarman report – said that institutional racism was not present in the police, and green-lit the continuation of surveillance in the form of “community policing”, and intensified levels of stop and search. A few years later, in 1985, unrest broke out again in Brixton, and subsequently in Peckham and Toxteth after police shot Cherry Groce, a black woman, paralysing her from the waist down. A week later, unrest breaks out in the Broadwater Farm estate in Tottenham after Cynthia Jarrett, a black woman, dies during a police search at her home.

Institutional racism and the lie of multiculturalism

As we move into the 90s, another flashpoint in anti-racist organising occurs: in 1993 the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence in Eltham marks the beginning of a 20-year campaign for justice led by his mother Doreen Lawrence. Alongside the campaign, the Macpherson report commissioned by the government documents that institutional racism and corruption is rife in the police force and Crown Prosecution Service. Government-commissioned reports and reviews appear to bring policy changes and reforms, but in no way substitute the necessary collective power of anti-racism movements. The institution of the police was not designed for us or by us; their role is to protect property and break up working-class dissent. Poet Benjamin Zephaniah writes at the time, reflecting on Stephen’s death and the willful mis-management of the murder case: “Racism is easy when you have friends in high places”.

As we move forwards into the late 90s and 00s, the country is led by Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair under the banner of “multiculturalism”, but in reality not differing hugely from the approach of Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher who placed heavy emphasis on nationalism and British “values”. Under Tony Blair, Labour’s focus pivots from class struggle to a much more depoliticised sense of “community”, with its obsession with “integration” and accompanying neo-colonial and imperial pursuits and wars framed as humanitarianism and missions to bomb democracy into other countries.

State-sanctioned Islamophobia ramps up in the Blair years, as the Prime Minister uses the London bombings in 2005 as a launchpad to express his “resentment” that the UK’s “openness, our willingness to welcome difference, our pride in being home to many cultures, is being used against us; abused, indeed, in order to harm us”. This signals the exposure of the artifice of multiculturalism. Hypocrisy is evident in the superficial cherry-picking of elements of “culture” from other countries that are seen as benign (sometimes referred to as the “samosas, saris and steel bands” approach) while providing the context for violent racism through proliferating racist attitudes, legislating to curb immigration, and carrying out atrocities in the name of foreign policy.

Civil unrest in the digital age

As we move into a decade of Conservative government, characterised by wholesale public funding cuts and the construction of a racist web of “hostile environment” policies, in 2011 a peaceful march to Tottenham police station is held after the police killing of Mark Duggan. When the police fail to provide satisfactory answers for the protestors, and in light of the IOPC (the body tasked with investigating the police) releasing a statement that suggested (incorrectly) that shots had been fired at officers before Duggan was killed, civil unrest breaks out and spreads to Birmingham, Leicester, Liverpool, Manchester, Nottingham and more.

As the riots unfolded, politicians quibbled over whether to attack rioters with water cannons, and David Cameron stated that the country was experiencing “moral collapse” and that he intended to embark on a “war on gangs”. 3,000 people were arrested during the 2011 civil unrest, a disproportionate amount (39%) of whom were black. In the wake of the riots, a racially-biased gangs matrix is created: a database which largely criminalises black men, and breaches privacy rights by sharing data with other authorities. It continues to be evident that the criminal justice system is racist from top to bottom. Powerful collectives and campaigns are formed in the years that follow, working to chip away at the matrix and other aspects of the system such as sentencing laws (like Joint Enterprise), prison expansion with a view to prioritising care over-incarceration, state violence, deaths in custody, the immigration detention estate, deportation and more. These groups, in different ways, continue to work to achieve immediate material improvements to our lives – such as holding police accountable for murder – while also strategising for a future world where systems of harm are ultimately abolished.

We still can’t breathe

Black Lives Matter is a decentralised network of anti-racist organising founded in the US in 2013 by three black women: Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi. Black Lives Matter was formed in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who shot Trayvon Martin in 2012. Street protests erupted the following year after the shootings of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner in New York, and Black Lives Matter demonstrations continued in support of black people killed by police.

The UK chapter of Black Lives Matter (BLM UK) emerged in 2016, and called attention to racism in the UK by blocking a motorway near Heathrow airport on the fifth anniversary of the murder of Mark Duggan. The action drew attention to deaths in custody such as Mzee Mohammed, Sarah Reed, and Jermaine Baker, as well as making links between racist immigration policy and high numbers of people dying in the mediterranean sea as the “migrant crisis” intensified, as well as the rise in hate crimes after the EU referendum vote a few months prior. The following year, BLM UK protested at City Airport due to the racism of climate change: Britain is the biggest contributor to global temperature change while the vast majority of countries vulnerable to climate change are in sub-Saharan Africa. BLM UK made important connections between Britain’s colonial history and its capitalist present, in which profits are prioritised over black lives.

“Black Lives Matter is still growing and evolving, as all movements do”

This long and meandering history teaches us important lessons. For one: Black Lives Matter is still growing and evolving, as all movements do: in Patrisse’s 2018 memoir she confronts the movement’s failure early in the struggle to centre perspectives and contributions of transgender women of colour, and she grapples with the dangers of “burnout culture”. We can also see the vital importance of movements linking in with each other and not working in silos. It is vital that the environment movement, worker’s struggles and trade unionism, migrant’s rights movements, queer and trans justice movements, disability justice movements, feminist movements, and anti-racist organising and more, all engage in meaningful dialogue and solidarity work with each other. We will mess up along the way, but we can come ready to listen, learn, and heal together. We must adopt an ever-moving practice of reflecting and recognising whose voices are being heard and how different tactics include and exclude.

History is cyclical. We must prepare ourselves for the moment – it might be next week or next month – when white people begin to lose interest, again, in anti-racism. We will continue to fight because we have been fighting, and there is no other way. The organisers who come before us have led the way; they were not perfect, and neither are we. We do not have the desire to opt out of blackness, or the privilege to switch off the news and take a break from oppression. The most important lesson is that without radical care for each other and our communities, we will burn out. This week, the struggle might look like nourishing ourselves – through food, friends, books, walks, soft fabrics and feeling the breeze on our face through an open window. By treating ourselves like we would treat a cherished friend or lover, we can fuel the gentle fires for the next chapter in the histories we are writing together.