Back in 2006, when I first got my period, smartphones were very much in their infancy – we were still in Blackberry days, exchanging BBM pins with first crushes. Our digital footprints were non-existent, nor were we as reliant on our devices. We, the millennial generation, were at this point still counting the days in our menstrual cycles. Today, however, 100 million people with periods worldwide rely on a variety of apps to manage, track and better understand ovarian activity.

This strain of apps are lifting some of the stigmas surrounding menstruation. They allow the user to feel control over their menses, fertility and (premenstrual syndrome (PMS), all of which can sometimes catch one off-guard. The complex algorithms behind the apps learn with each data point that a user inputs, each of which is associated with a symptom and helps to build an increasingly accurate picture of the user’s menstrual cycle.

In September 2019, a study conducted by Privacy International revealed that a number of menstruation and fertility tracking apps were exploiting these data entries and selling users’ data for commercial purposes. Whilst the worst offending apps, and those taking extensive measures to protect user data, were explicitly highlighted in the report, it is worth understanding how such intimate data is collected, and how it fits in with our wider digital footprint. Having downloaded a very pink set of apps – Clue, Flo, Natural Cycles, Period Diary and Eve – I dove into their Terms of Use and Privacy Policies.

“In all of the privacy policies, it is stated that all of the apps share data, even if it is anonymised, pseudonymised, or tagged to a unique identifier”

All of the apps’ privacy policies were keen to make it known that they would never share sensitive personal data with third parties, with the exception of Eve, whose welcome screen declared it part of my “period positive, sex positive, body positive squad”. Nonchalantly, their policy states that they “may combine [the user’s] personal data with information [they] collect from other companies and use it to improve and personalize the Services, content and communications with [the user].” The carefully crafted statement had obviously avoided using the word “share”.

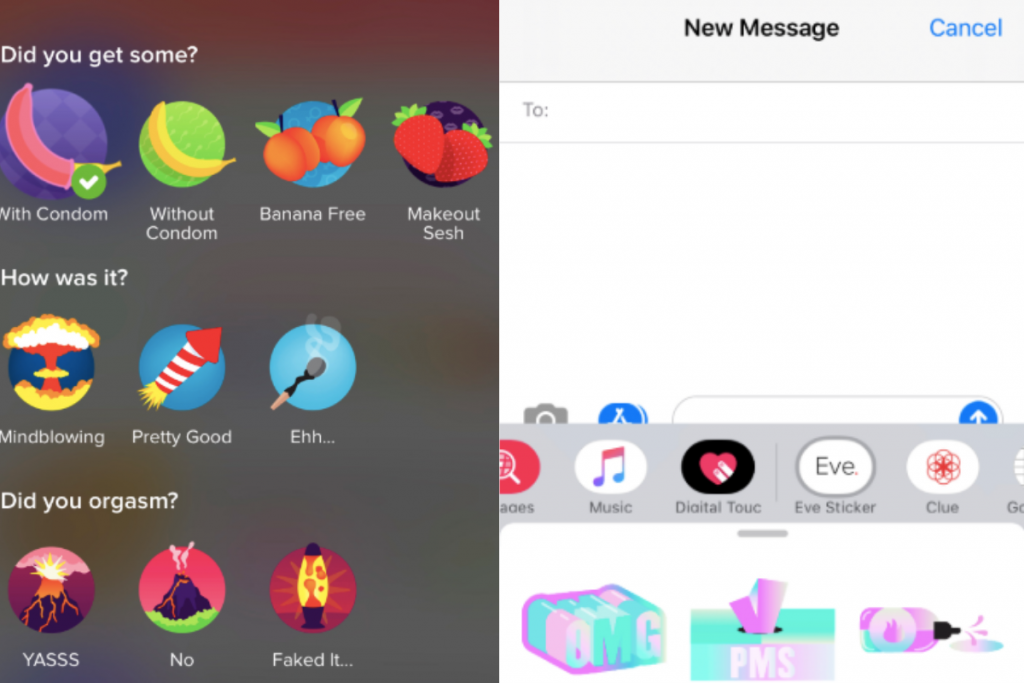

One way or other, in all of the privacy policies, it is stated that all of the apps share data, even if it is anonymised, pseudonymised, or tagged to a unique identifier. Not only do they all seem to work with health researchers, who become privy to the anonymised data, but on a functional level, the apps need a platform to exist and a network service provider to operate. They often use partner technologies to track business progress using performance analytics. Some of the apps integrate themselves into your operating system, synchronising with Apple’s HealthKit or GoogleFit – as soon as I downloaded the apps, I found that Eve and Clue had nestled themselves into the iMessage functionality on my phone, offering fun digital stickers that sport period paraphernalia. Whilst the apps themselves might not be mistreating your data, the very way that they operate might expose you to that risk anyway.

Our collective level of comfort with the data being shared largely depends, predictably, on what that data is. There is personal data, defined by General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) as anything that can directly be traced back to the user as an individual. Then there is sensitive personal data, facts about individuals that even their close family and friends may not know – health data, for example – which, in the context of menstruation is terrifyingly sensitive.

Clue collects data entries about sexual activity, whether the user went to a party and what they did at said party. Flo goes one step further, asking whether the sex was protected, how high your sex drive was, and whether you masturbated. Eve, disturbingly, questions whether the user’s feelings are related to their love life, their friends or their work, and whether the user orgasmed during sex. It is simply a mystery how the algorithm spits a result out with these data inputs – how exactly does a “makeout sesh” impact on my period?

There will always be a case to be made around fully understanding the physical and psychological factors that impact menstruation. The Black Mirror-esque fear arises when or if that data is then inputted into tools like Facebook Audience Insights, a platform that openly targets ads using data points such as relationship status. Eve, a Californian creation having perhaps not quite caught up with GDPR regulation, openly admits to profiling and automated decision-making.

And, rather darkly, that is maybe the only thing that these apps are any good for. As Adele Major writes in an article about period-tracking interfaces, “periods are not a finite measurement”,for example if data is entered incorrectly, which begs the question of why these apps exist at all. The ironically-named Natural Cycles has a user manual that highlights that the service does not work for those with risky pregnancies, those undergoing hormonal treatment, or breastfeeding mothers. By process of elimination, a period-tracking app then only works for non-mother, non-menopausal, cis-gendered women, which is echoed by research suggesting that the design of such apps can “create feelings of exclusion for gender and sexual minorities” and “fail to consider life stages that women experience”.

“Black women are almost twice as likely to experience infertility than white women, but the default whiteness of these apps conveniently ignores this data point”

As I begin to input my data into all five apps, I am also conveniently never asked about my ethnicity. This reveals the whitewashed discussions around menstrual health, ironically in a time when fertility is declining amongst marginalised women. Rachel Moss highlights that black women are almost twice as likely to experience infertility than white women, but the default whiteness of these apps conveniently ignores this data point, contributing to a harmful stereotype that “black people / people of colour do not experience fertility issues’,’ says Yvonne John, in a Huffpost article – she also launched Gateway Women to combat this very idea.

Natural Cycles’ user manual suggests that “stress” might have an impact on a menstrual cycle. Not only is that laudibly vague, but these apps do not have the capability to highlight some of the systematic and societal issues that may be causing said stress. As Miranda Hall writes for Motherboard: “Precarious jobs will inevitably fuck up your sleeping patterns. Institutional racism and homophobia mean that people of colour or gay people are statistically more likely to suffer from anxiety or depression. Ready meals or takeout become the default dinner as working class parents are forced to work longer hours…” This alone proves that health is more complex than a bodily examination and even a mental health check: health is social, economic, environmental and political.

“It is simply a mystery how the algorithm spits a result out with these data inputs – how exactly does a ‘makeout sesh’ impact on my period?”

These apps are aware of their own fallibility. Clue is peppered with academic references, as if to give itself a scientific pat-on-the-back, and all of the Privacy Policies state that they would not be responsible for a data leak should it happen. Users are left with all of the risk, despite having been asked for this information for accurate predictions. Chupadados, a Latin American project that encourages consumers to be aware of their digital footprints and coding rights, outlines the following questions we should be asking of menstrual tracking apps, if not every app we download: “What are we giving them and what do we receive in return? What rules and norms apply to this monitoring? Who designed the apps and set the norms? What values and presumptions orient the evaluations made? What type of knowledge are we producing and who is benefiting? What principles should be observed?”

And all hope is not lost; on both Android and iOS devices, you can reset your advertising ID such that the aggregated data about you is completely wiped, as well as opting out of personalised advertising. Do this before ads for indulgent, “treat yourself” purchases begin suspiciously popping up on your Facebook feed a couple of days before your period is scheduled to arrive.