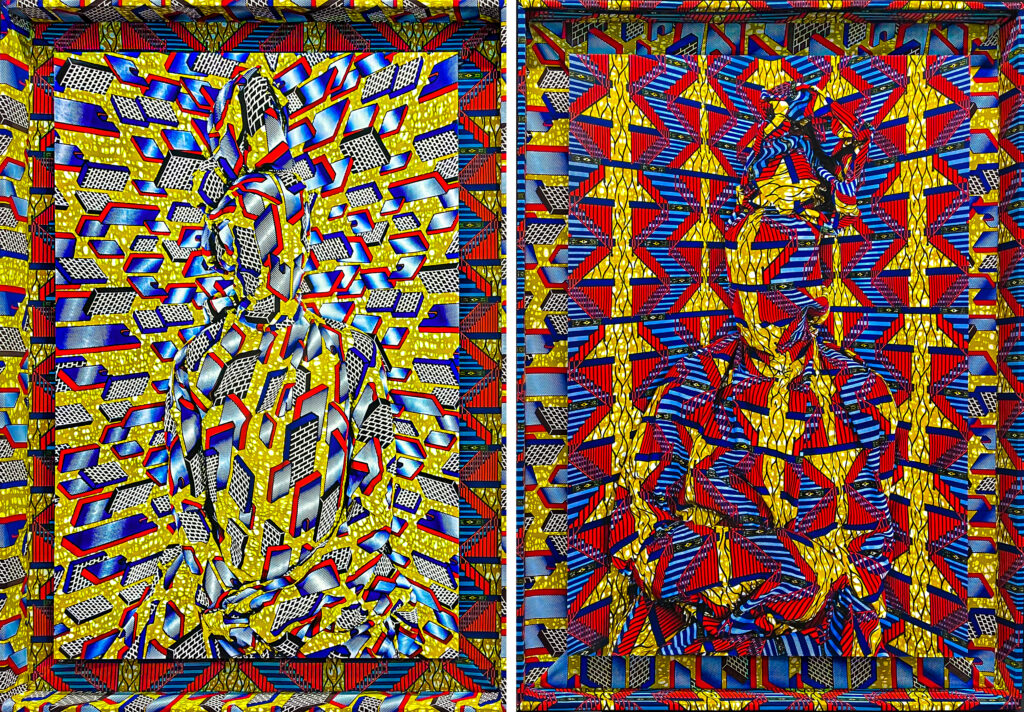

Still from Alberta Whittle’s RESET, 2020. Image courtesy of Alberta Whittle.

Here’s a forecast of what to expect from art next year

21 artists, curators and visionaries gaze into the future after two years of closures and uncertainty.

Precious Adesina

20 Dec 2021

For prolonged periods over the past two years, the halls of museums and galleries in the UK have been forcibly emptied. The first time was in March 2020, when the country’s restrictions were tightened as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, and again in November last year when the tier system was introduced. On both occasions, there was no obvious date for when Britain’s arts institutions, both big and small, would be allowed to welcome people through their doors again. Events were delayed, made virtual or, in the worst case scenario, scrapped entirely – something many spaces are still recovering from today. Even now, with the rising cases due to the Omicron variant, it feels as if we are teetering on that precipice of uncertainty once again.

A heightened focus on moving the art world online in recent years has seen more people choosing to showcase their work on the internet in the form of virtual talks, events, tours and more surprisingly as a non-fungible token or NFT – which has been mentioned more times this year than ever before, so much so that it was Collins Dictionary’s word of the year.

For artists of colour, especially black artists, the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests and their impact have stirred questions over whose work is being shown and how. The discussions have been two-fold. Firstly, it shouldn’t take the murder of a black man for the struggles of marganlised communities in different industries and beyond to be acknowledged. But, more positively, the movement has also made it difficult for people to ignore where we have come from and how much more we still have to do.

Here, we speak to 21 people about where they see art by people of colour heading both culturally and aesthetically in 2022 and beyond.

Adelaide Damoah, painter and performance artist

Over the last 40 years or so, academics have said that it is the responsibility of black artists to produce work that is actively involved in the struggle for equality. Whether artists of colour really do have a duty to do that or not is another discussion, but we are moving towards a time where more feel liberated from that. The great Okwui Enwezor once said that global art (read: art made by non-white people) should be spoken about in conversation with, rather than in opposition to, the Western art canon. I believe that the future of art by people of colour is one that is doing exactly what he said it should do: having a global, broader, honest conversation with itself.

Tokini Peterside, CEO and co-founder of ART X Lagos

Artists of colour consistently create work that pushes boundaries. They de-centre existing – often Western or colonial – paradigms and imagine new, more equitable futures. I think we will see artists of colour from all over the world continue to do what they have done for millennia: telling their stories and expressing themselves and their cultures in ways that are unique, thought-provoking, refreshing and powerful.

Malene Barnett, founder of the Black Artists + Designers Guild

Black and brown artists are digging deeper into their culture and history. Currently, NFTs are dominating the marketplace, and I believe black artists will create platforms that reflect their experiences for the medium.

Zoe Whitley, director at Chisenhale Gallery

There’s a real emphasis on the senses, especially sound. There are so many people who we might have previously thought of as recording artists creating artworks. We’ve spent so much time behind closed doors – I believe these works have something to do with what it means for us to gather and listen.

Alberta Whittle, artist and researcher

Black artists and artists of colour have been increasingly commanding recognition of structural inequalities whilst making joy, pleasure and exhaustion visible and challenging. Varied modes of expression from Zinzi Minott’s defiant Fi Dem series to Sekai Machache’s contemplative examinations of time, spirituality and language, artmaking from Black artists and artists of colour is refusing to be pigeon-holed as a singular conversation about oppression. We continue to explore the world and the world we want to make by running the gamut of speculative thinking around self-love, unlearning and refusal.

Mai Eldib, head of sales at Sotheby’s, Dubai

The international secondary market [art that has been sold at least once before] has always been skewed towards the work of white – and predominantly male – artists. In the past, Sotheby’s most important auctions focused on works by widely-known artists with established auction histories. Today, we build them around artists who we believe are most deserving of this global platform, even if they have only just started making waves in their careers. There is also the growing enthusiasm for collectors to support artists from their own backgrounds – rather than being automatically drawn to the most famous international artists. The prices for works by young artists of colour are certainly on the rise, as people are beginning to actively broaden the canon.

Mattie Loyce, interdisciplinary artist and curator

There are activist-based groups and DJ collectives – not necessarily in the visual art realm are [teaming together in the absence of institutions]. WE ARE THE ONES WE’VE BEEN WAITING FOR started the #ARMTHEGIRLS initiative which did fundraising and collaboration with Telfar to provide trans women and gender non-conforming POC with protective bags that included pepper spray and tasers in a cute purse. There’s a lot of mutual aid, individuation and residency retreats. Many artists have created their own safe havens or retreated to their studios because of the pandemic. They’ve also been working more with smaller organisations as they are able to turn things around faster than bigger institutions.

“Many artists have created their own safe havens or retreated to their studios because of the pandemic”

Carina Tenewaa Kanbi and Victoria Cook, founders of AYA Edition

Female creatives in West Africa are still struggling to achieve the same prominence as men, but we think 2022 will see a change in the status quo. Alongside pioneering figures such as Joana Choumali and Elisabeth Efua Sutherland, keep an eye out for the new vanguard artists such as Afia Prempeh and Araba Opoku, who are creating works that redefine the canon, from figurative photorealism to surrealist works.

Ebun Sodipo, artist, writer and model

I’m wary of presenting artists of colour as a monolith. That being said, among the artists I engage with, I see more work playing with archives, history, fiction and storytelling. There is an inclination towards different forms of nostalgia and many of these artists are also interested in the body: its physical presence, its discursive nature and its mutability.

Amrita Dhallu, assistant curator of international art at Tate Modern, and co-curator of Lubaina Himid

Worldbuilding, [creating imaginary worlds], has been embraced by artists. Exhibitions such as Lubaina Himid’s retrospective at Tate Modern transform the gallery space into a site where many of us can congregate, converse and even time travel together as we move from one reality to the next with each canvas.

Ferren Gipson, art historian

When I think about Simone Leigh representing the United States and Sonia Boyce representing Britain in the 2022 Venice Biennale (each the first black woman to do so for their respective country), I feel excited about where things are heading for women artists and artists of colour. Lubaina Himid’s Tate Modern exhibition is equally fantastic, and we mustn’t forget that she also broke age records when she won the Turner Prize in 2017. What will be important to watch moving forward is how artists from diverse backgrounds are represented in art historical texts and museum collections in a way that is permanent and meaningful.

Layla Andrews, artist

I think this is a very exciting time for art. We are moving to a stage where artists of colour feel comfortable creating whatever they want, for whatever reason they want. They will be disregarding any predetermined notions of what artists of colour should contribute to the art industry and proudly displaying their own identities in whatever way they see fit. Freedom to create will ensure a plethora of diverse artworks.

Hannah Gottlieb-Graham, founder and director at ALMA Communications

I started my company as a way to work directly with artists, brands, creatives and institutions confronting important questions around issues like class, climate, identity, race and social justice. In the past two years, I’ve seen white-owned or led companies finally start to understand the importance of having these dialogues. What I worry about, though, is how artists, founders and institutions of colour will be supported by their white counterparts long-term. I think there’s enormous pressure for POC artists – and especially young artists – to churn out work quickly and sell fast. I imagine that the combination of artistic liberation and extreme pressure is difficult to reckon with as an artist, and I’m curious to see where things go in the next five years.

Jess Au, co-founder of 2B or Not 2B Collective

Brexit and the pandemic are monumental things to have happened in our lifetime and I can’t see that not influencing BIPOC artists. NFTs will also most likely peak next year as they trickle into the mainstream. Just like the internet and social media gave access to free marketing and an international audience, we’ll see a new wave of marginalised and BIPOC artists come to the forefront in the NFT world. Although the industry is not without criticism in terms of environmental damage and perpetuation of oppressive systems, it will be interesting to see how it can be a tool used to combat systemic inequality, lack of diversity and access in the art world.

“We’ll see a new wave of marginalised and BIPOC artists come to the forefront in the NFT world”

Aïcha Mehrez, assistant curator at Tate Britain

Now that people of colour are gaining more visibility in the wider art world (we’ve always been visible to each other) we are able to unsettle fixed narratives of nationhood and belonging. My hope for the future of the art world is that people of colour will continue to feel able to express themselves in a way that defies any expectation placed upon them.

Aindrea Emelife, art historian, critic and curator

The past two years of socio-political uprising and upturning is evidence of the fact that history is accelerating. This year has seen landmark exhibitions signifying more diverse programming; numerous employments of curators and directors of colour; and wider recognition for a greater array of artists. But, we must not be complacent. I’m looking to find meaning amidst this rupture – actively ushering us towards a transformed reality of the art world that many of us long to inhabit.

KK Obi, editor and creative director at Boy Brother Friend

In all my conversations with my peers, there is a sense that there aren’t any limits to one’s message anymore. There is an unabashed fearlessness in expressing and centring their ideas on the main stages of culture, fashion, music and visual art. This feels like a radical, political and generational shift – one that refuses to be constrained by expectations of others. Culturally, we’re seeing closer relationships, interaction and support in the way we all work.

Marcellina Akpojotor, artist

The communities these artists and curators come from are developing. More spaces and opportunities are opening up for younger artists. The Young Contemporaries program by Rele Art Foundation in Lagos is a good example. I was a beneficiary and was given the opportunity alongside others to exhibit my work and connect with other artists. They’ve also started to feature artists from other parts of Africa. Established artists are also using their resources to support their local arts communities. There is the ANAI foundation by Peju Alatise; Black Rock in Senegal by Kehinde Wiley; and Angels and Muse in Lagos by Victor Ehikhamenor, which is another creative hub that stages events.

Alia Ali, photographer

It’s a time in which we are not entering the artistic paradigm from a position of defending our narratives but rather shifting the departure point of dialogues we want to have from where we set the point- not where it has been set for us.

Angie Bual, co-director of Trigger and creative director of PoliNations

I think art by people of colour is only going to get more interesting and unexpected. As an artist, I want to see more intersectionality in the way we talk about artworks and the artists behind them – to move beyond acronyms like ‘POC’, ‘BIPOC’, ‘BAME’ to build a deeper understanding of who an artist is and what they are trying to communicate.

Alayo Akinkugbe, founder of A Black History of Art

There has been a distinct rise in attention given to the black figure in painting recently. Next year, I hope that the mainstream will move away from the representation of the black figure as essential to the understanding of art by black people and that more attention will be given to artists whose work does not explicitly represent it. I think 2022 will have an emphasis on artists working in 3D, for instance, Theaster Gates, who will be the first non-architect to design the Serpentine Pavilion, and who has a show on at Whitechapel Gallery at the moment.