Inside the campaign against the ‘Genocide Games’ disrupting the Beijing Winter Olympics

As China prepares to host the Games, a coalition of activists are refusing to let state human rights abuses go ignored.

Pema Monaghan

24 Jan 2022

Diyora Shadijanova

On 4 February, the 2022 Winter Olympics will kick off in Beijing, despite the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic and China’s ‘Zero Covid’ approach throwing plans into disarray. But Covid-19 is not the only obstacle facing the games.

Last October’s Olympic flame lighting ceremony in Greece did not go quite as expected. As an actor playing the goddess Hera completed the ceremonial lighting of the flame, a trio of activists disrupted the ceremony, shouting for a boycott of the games. Above them, fluttering in the wind, they carried a Tibetan flag and a banner reading ‘No Genocide Games’.

The activists belonged to a coalition of Tibetan, Uyghur and Hongkonger diaspora communities and Chinese democracy groups, who are organising furiously ahead of the 2022 Winter Olympics. They were in Ancient Olympia to send a clear message: to participate in Beijing 2022 is to be complicit in Chinese government’s crimes against human rights, particularly the genocide against Uyghur people and the active dismantling of Hong Kong’s free press and civil society.

The events of last October echoed similar protests against the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, co-ordinated largely by Tibetans, both those living in Tibet and in the diaspora.

The Chinese government responded with violence, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 99 Tibetans during demonstrations. Consequently, Chinese authorities tightened their grip on Tibet, including a media blackout that is still in effect today. Fourteen years on, and as Beijing increasingly asserts its dominance across East Turkestan, Hong Kong, Tibet and Taiwan with chilling effect, protesters around the world are still daring to draw attention to what they’re calling the ‘Genocide Games’.

Boycotting Beijing

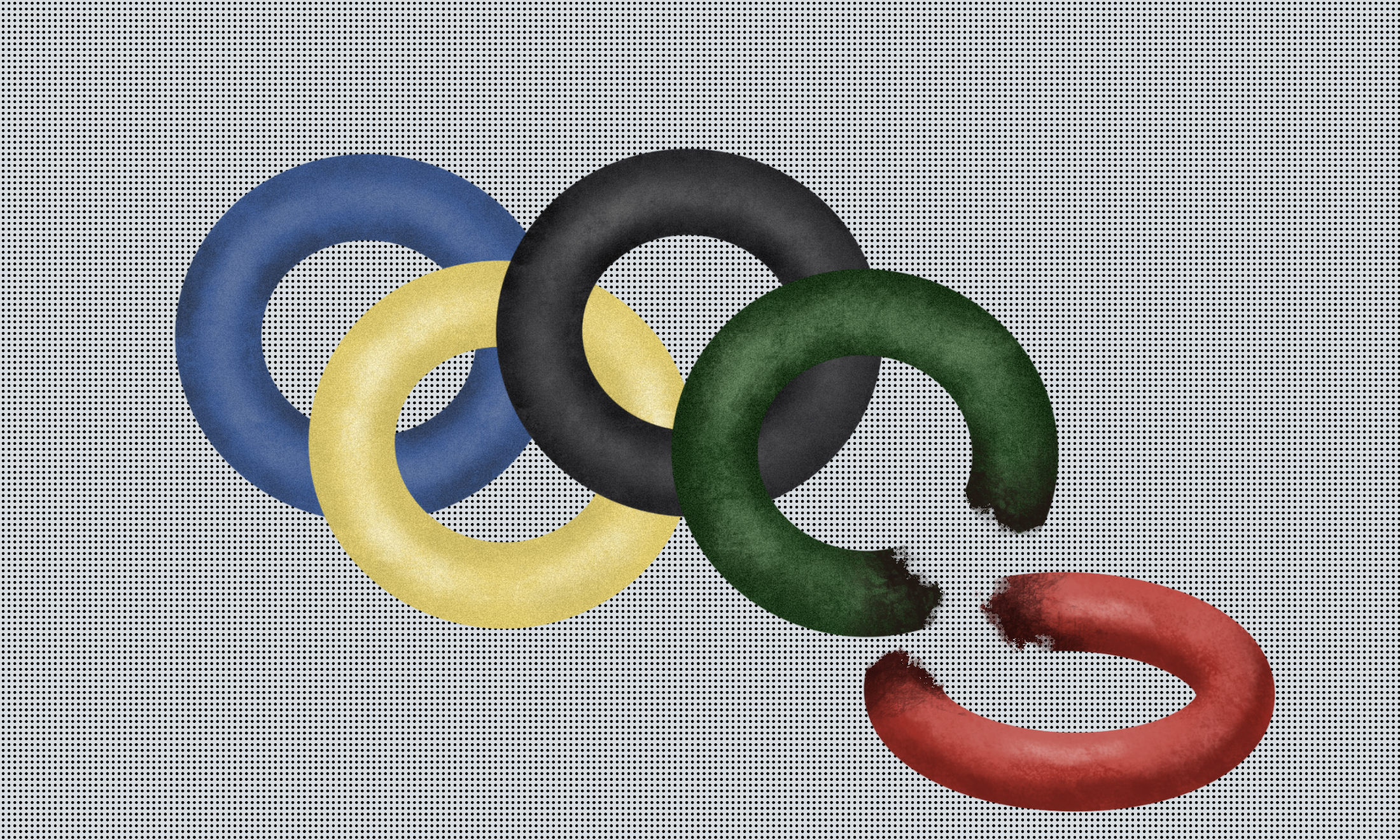

Action has been substantial and sustained. Since October 2021, activists have participated in events ranging from sit-ins at the International Olympic Committee headquarters, two day vigils outside the US White House and chaining themselves to the Olympic Rings.

Pema Doma, 27, campaign director for Students for a Free Tibet, a grassroots organisation who have taken a major role in the coordination of the protests, spoke to gal-dem about the White House vigil over Zoom from her office in New York.

“A group of around five young Tibetan, Uyghur and Hong Kongers students were sleeping outside of the White House for 57 hours leading up to the [November 2021] US – China Summit,” she recounts. “Their number one demand was ‘do not go to the Beijing Olympics, President Biden.’”

A few days after their vigil on 7 December, US officials confirmed that the White House would not be sending a political delegation to the Games, citing the People’s Republic of China’s “egregious human rights abuses and atrocities in Xinjiang”.

Australia, Canada and the UK quickly followed suit in announcing that no government delegations would attend the Winter Games, also citing human rights abuses. Denmark has now also decided not to send a diplomatic delegation due to human rights concerns. Japan has similarly decided against sending its diplomats, although leaders are shying away from referring to the move as a “boycott”.

“A group of around five young Tibetan, Uyghur and Hong Kongers students were sleeping outside of the White House for 57 hours”

Nevertheless, these countries will still be sending athletes to compete for medals in Beijing. Around 50 athletes will be representing Britain; in December British prime minister, Boris Johnson told the UK parliament that “we do not support sporting boycotts”.

Activists working to disrupt the Beijing games are less than impressed.

“They [Western heads of state] have done the bare minimum in response to the escalating violence and repression of the Chinese Communist Party [CCP],” says Pema, referencing not only the genocide against the Uyghur people, but also the residential boarding schooling programmes inside Tibet, which “seek to virtually eradicate Tibetan identity within a single generation”.

Pema says that the escalations in offenses by the CCP are provoking heightened responses from foreign governments in kind, though not severe enough or fast enough.

Frances Hui, a 21-year old journalist and director of We The Hongkongers, who now lives in Washington, D.C., after fleeing her home, agrees.

“The world leaders are only responding in a trickle,” Frances says. “And what we need to be seeing is really an opening of floodgates against the genocidal regime of the CCP.

Sporting behaviour

The coalition against Beijing 2022 are realistic about the slim chances that heads of state will announce complete boycotts of the Winter Games (which would mean neither diplomatic or athlete delegations would be in attendance in February). So, they’ve turned their attention to the athletes themselves, asking sportspeople to reach out and ask questions about the protests and to consider ways they could acknowledge the human rights issues at the Olympics if they are unable to fully boycott the Games.

Frances suggests that there are alternatives to deciding not to participate in the Winter Olympics at all. “[Athletes] can do some sort of protest when they’re in Beijing, like a small kind of protest with their hands, or gestures”.

The coalition are well aware of the difficult choice facing Olympians.

“We really do want athletes to hear what we’re saying and to dialogue with impacted communities, whatever they choose to do. We understand how important it is for athletes,” says Pema.

“We really are doing our best to be empathetic and see things from their perspective. But we’re also asking if they can see things from our perspective. If they as a human being had their entire family locked up, or if they were never allowed to travel freely, if they weren’t given a passport or if they lost access to freedom of speech, would they say that athletics was more important?”

Frances Hui has participated in videos on social media alongside Uyghur activist Zumretay Arkin and Tibetan activist Chemi Lhamo, urging 2022 Olympians to reach out to the coalition. ”We hope that athletes as individuals can think through whether they want to be part of a game [when it] is a bloody game,” she tells gal-dem.

The Beijing organising committee have recently given athletes reason to fear making public protest. Yang Shu, deputy director of international relations for the Beijing organising committee threatened that actions that went against “Olympic spirit” or Chinese law would result in “certain punishment”.

So what is the Olympic spirit? In response to the diplomatic boycotts during a press conference given 8 December 2021, IOC President Jonathan Bach said that diplomatic delegations were a “purely political decision for each government”, but that he was glad athletes would be allowed to participate without intervention, reiterating the “political neutrality of the IOC”.

“When Tommie Smith and John Carlos protested the rates of Black Americans living in poverty while collecting their medals, they were expelled from the Games”

Bach referenced the ‘Olympic Truce’ entered into by UN nation states, in which participating countries agree to suspend political disputes during the Games. The aim of the ‘Truce’ is to use “sport to build bridges and promote dialogue and reconciliation in peaceful competition by bringing the entire world together”.

However, the question of ‘dialogue’ at the Games has long been a fraught one. While athletes have previously used the space afforded to them in Olympic stadiums to protest, they have also been punished for it. When Tommie Smith and John Carlos, sprint winners at the 1968 Mexico Games, protested the rates of Black Americans living in poverty while collecting their medals, they were expelled from the Games. The IOC called their actions a breach of “Olympic spirit”.

As of 2021, the IOC has permitted athletes to wear political clothing or express political opinions before and after athletic events – but not during them. Of course, the most powerful moment to make a statement is the one in which all eyes are on you: while setting a record or accepting a medal.

The IOC have also recently received criticism for their handling of the case of Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai, who vanished for two weeks after posting an account of sexual assault by Zhang Gaoli, an ex-vice premier, to her social media. Shuai is a three-time Olympian and is expected to attend the upcoming Winter Olympics in Beijing. In response to public concern, the IOC announced that they had held two video calls with Shuai since her initial disappearance, releasing screenshots of Jonathan Bach holding a virtual conversation with the star in which the IOC say she appeared “safe and well”, and that they would continue to use a “person-centred approach” of “quiet diplomacy” with China with regards to the case.

Various recordings of Shuai released by Chinese state media journalists have done little to allay international calls of concern for her safety, with doubts cast over their authenticity. The IOC have been accused of participating in painting over Shuai’s accusations and assisting in constructing a staged video to allay doubts over her safety.

Human rights advocates have warned athletes that public criticism of China at the games might put them in the way of similar harm from the Chinese government. The IOC’s insistence on the value of “quiet diplomacy” may not be enough to assure athletes of their safety should they run into trouble with their host nation.

Audiences at home

The #noBeijing2022 coalition has also called on Olympic broadcasters to reconsider their investments in the Games. Broadcasters typically pay billions to secure the rights to air the Games. Beijing 2022 will be aired by the BBC in the UK, and NBC in the US.

Pema Doma says that private media companies who have chosen to partner with the Beijing Games have made a mistake. “These broadcasters have now put themselves in a position where more awareness about human rights violations and more concerns about the CCP are actually going to result in less business for them.”

“If you’re a broadcasting company, and you’re tying your company’s profits directly with the successful sports-washing of human rights abuses, you should be able to raise a red flag and say you’re doing something wrong,” she says. “This is the farthest thing from just another Olympics.”

While Frances Hui is not hopeful that broadcasters will renege on prestige contracts, she says that coverage could include discussion of the human rights abuses occurring in China. She asks that consumers who care about the issues also make their voices heard, advising viewers to: “Call on those sponsoring companies, and tag your athletes, and tell them what’s going on in China.”

“There’s other geopolitical concerns at play too, of course; Australia and China are involved in trade disputes”

Frances understands that Westerners who are unfamiliar with the history and politics of China might feel uncomfortable calling out the CCP’s human rights abuses. She says that CCP supporterson both social media and in state-owned news outlets like Global Times have occasionally tried to co-opt the wave of anti-racist solidarity with Asian people to prevent critique of the CCP.

“I think it’s very important for the world to understand: Anti-CCP is not equal to anti-Chinese,” says Frances. “We’re against the regime that is abusing human rights, we’re against the regime that is controlling our freedoms, and not allowing a diversity of voice to happen in society.”

The decision to announce diplomatic boycotts has forced Western governments, previously tentative in outright accusing China of genocide, to state out loud that China has crossed a line with regards to human rights abuses.

Boris Johnson, no stranger to the temptations of authoritarianism himself, has found this repositioning very difficult, evident in his mumbled confirmation of the boycott after being pushed by members of parliament.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison was equivocal in his denouncement of human rights abuses, easily letting genocide sit alongside “national interest” in his reasoning for the diplomatic boycott. There’s other geopolitical concerns at play too, of course; Australia and China are involved in trade disputes after China, once a great trading partner of Australia, began freezing trade last year after Morrison called for an independent inquiry into the origins of Covid-19.

China has responded to these boycotts mostly with a sullen shrug. Beijing foreign ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin has gone on record saying that: “nobody cares” if diplomatic delegations attend or not. The athletes are still coming, and Beijing will still get their “politically neutral” internationally televised sporting event, and that’s what counts. Perhaps. But the dogged efforts of the #noBeijing2022 coalition have cut through. The shine has irreversibly been taken off what was supposed to be an occasion of triumph for the CCP. Instead, a shadow has been cast over the games – one that won’t disappear with the closing ceremony, no matter how much the Chinese government tries to make it so.

This article was amended on 28 January to state that Pema Doma was speaking from New York and Frances Hui was speaking from Washington D.C. An earlier version mistakenly said Doma was speaking from Washington D.C. and Hui from New York.

How reconnecting with my Vietnamese heritage led me to write a novel

This Lunar New Year, Asian communities deserve the right to grieve and fear

All the bad bills the Tories are pushing through this year