How reconnecting with my Vietnamese heritage led me to write a novel

After learning about the Vietnamese Boat People, author Cecile Pin was inspired to write Wandering Souls.

Cecile Pin

27 Feb 2023

Ariane Lebon

Content warning: this article contains mention of racism and sexual abuse.

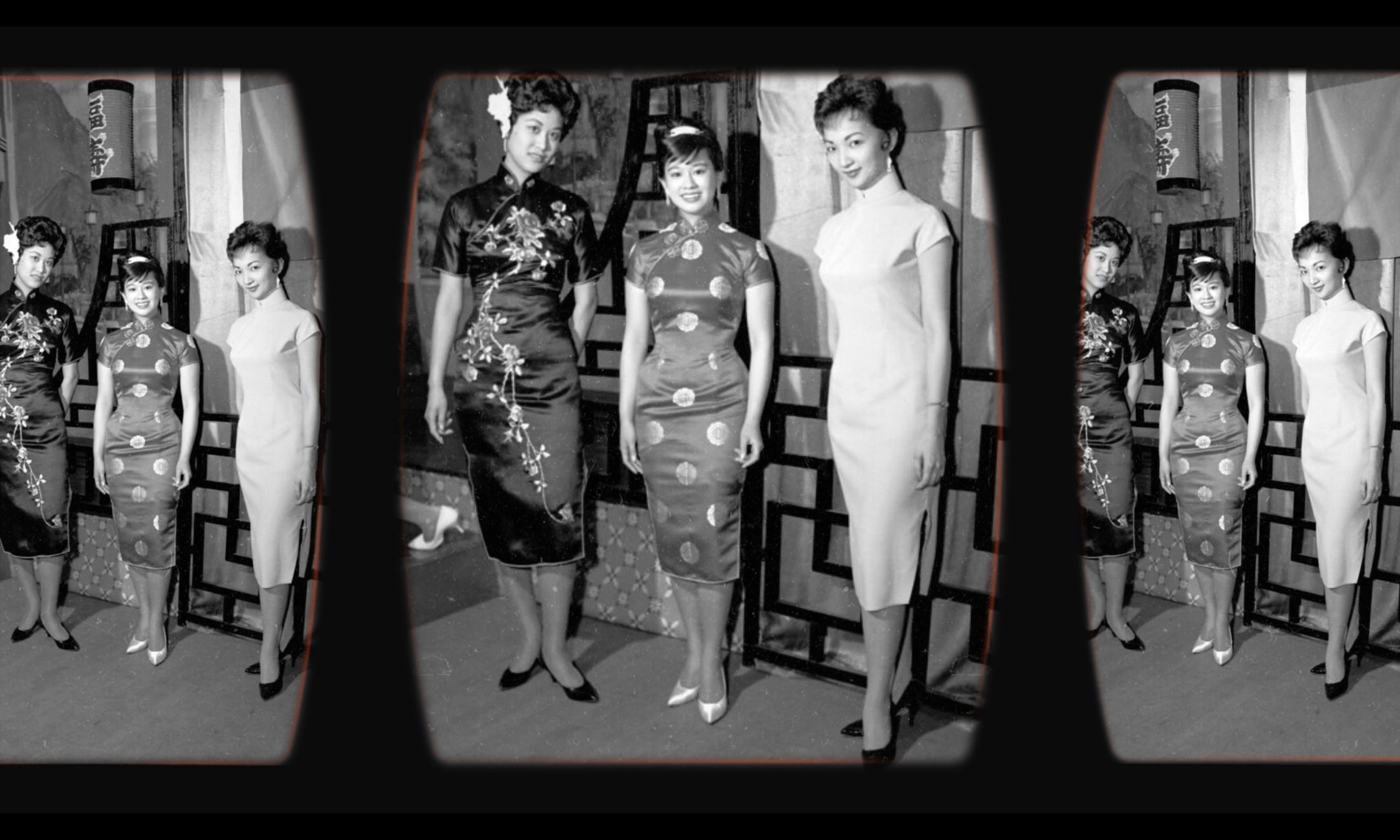

“I’m here for the casting,” I tell the receptionist of the studio, my modelling book in hand. She directs me to a door, where a familiar sight awaited me: a room filled with East and Southeast Asian women, all about my age. As some cautiously initiate small talk and others scroll their phones or read a book, I sit down on the remaining seat.

My father is white and French and my mother is Vietnamese. Growing up in France, with a brief stint in the US, my white heritage was put to the forefront, while I unintentionally minimised my Asian roots. Besides when interacting with my mother’s family, I did not feel a deep connection to my other heritage. I did not speak Vietnamese, nor did I have many Asian friends. White was my default state of being and I felt a slight disconnect with the other half of me.

“White was my default state of being and I felt a slight disconnect with the other half of me”

I moved to London when I was 18 for my studies. And at the same time, I noticed there was a discrepancy in how I saw myself and how others saw me. I became weary of men who tried to guess my ethnicities for painful long minutes on end (“Let me guess – Japanese? Thaï? Chinese?”).

My brief stint in modelling was also a turning point. I realised that I was always cast as the token Asian girl, usually in shoots consisting of a red head, a brunette or blonde, a Black model and… me. Being systematically compartmentalised in this way, put in a box whose label didn’t quite match who I was, felt diminishing. But it was also, unexpectedly, freeing: I realised that if this is how I was being perceived, I should also learn to embrace this side of me.

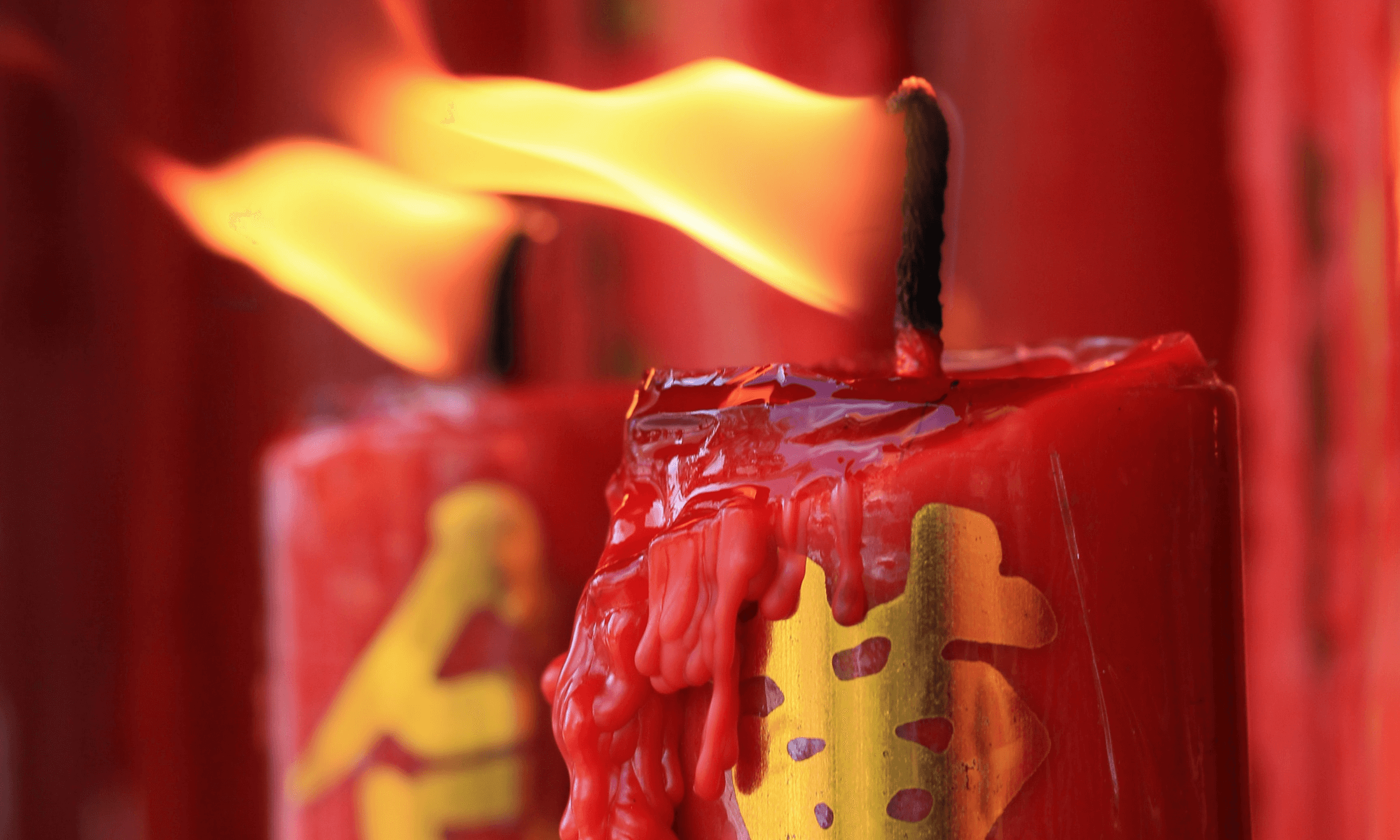

I began the steps to learn more about my Vietnamese heritage and, like a lot of second-generation immigrants, an easy access point was through cooking. I ventured inside Asian supermarkets, trying to find the same sauces and spices I had seen my mum use countless times. I asked her to send me the recipes for some of my favourite dishes, thịt Kho and phở and “that spicy sour soup you make with the green vegetable whose name I don’t know”.

“Each new dish I ate brought me closer to this heritage – each bite imbuing itself in me, a confirmation that I was, indeed, Vietnamese”

Each week I tried new recipes, becoming more familiar with each ingredient, more confident in eyeballing rather than using precise measurements (as is tradition in Asian cooking). And each new dish I ate brought me closer to this heritage – each bite imbuing itself in me, a confirmation that I was, indeed, Vietnamese.

And then, the pandemic happened. Covid-19, which Donald Trump saw fit to call “Kung Flu”, bolstered already rising anti-Asian hate. Every day, the news cycle would show me photos of Asian men and women beaten up and bruised; of lit-up police cars in front of crime scenes, including the Atlanta spa shooting in March 2021, where six Asian women were killed. The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University reported a 150% rise in Anti-Asian hate crimes across the US between 2019-2020.

While this violence was happening in the world, I thought back to all the microaggressions that had punctuated my childhood. The “ni haos” and “Chinetoque” (a French ethnic slur), the salespersons that had treated my relatives and me with contempt, aggressions that I had brushed off at the time as either jokes or ill-manners or ignorance, rather than racial discrimination. Feelings of gaslighting emerged: I wasn’t sure how much of what I was remembering was in my head and how much of it was real.

““I have struggled to prove myself into existence,” writes Cathy Park Hong. And there I was, trying to do the same; to make sense of my being”

The discrepancy between what felt real and what felt unreal had grown to a riotous level, and it became clear that cooking would not be sufficient to heal it. I began to take refuge in books, by reading works like Minor Feelings by Cathy Park Hong and Citizen by Claudia Rankine. These books gave me a better understanding of racism and validated all the emotions I had in me: the conflicted ones and the angry ones, and the ones hidden in the deepest corners of my mind. “I have struggled to prove myself into existence,” writes Cathy Park Hong. And there I was, trying to do the same; to make sense of my being.

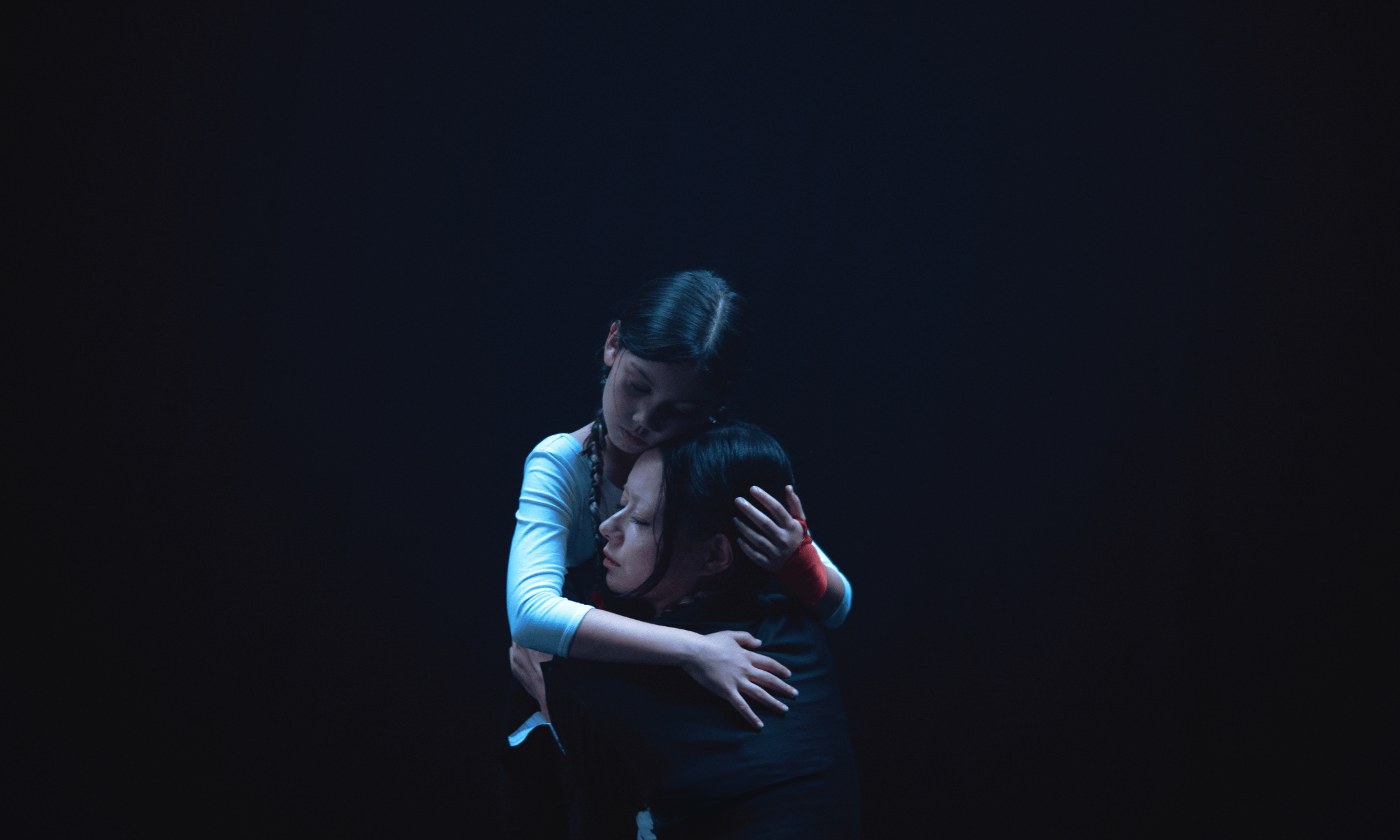

From an early age, I had learned a rough outline of my Vietnamese family’s journey to France in the 1970s. I knew that my mum had lost her parents and half of her siblings to the sea, and that they had spent some time at a refugee camp in Thailand. But I became hungry to know more. Not just about my own history, but that of all Vietnamese Boat People.

Late into the night, I would find myself, almost obsessively, reading testimonies of refugees who had now settled in the US, Germany and Australia: the losses they had suffered along the way, how they were welcomed, what the conditions of the refugee camps were like. It became a way for me to feel connected to my past, to this heritage that was half-obscured and yet mine. Some of it took a toll on me, especially when learning about how many of the refugees had been sexually abused and raped. This was not something I had considered, as a young child.

“It was proof that this community of refugees still existed, that they were here”

At the same time, I noticed that there was very little documentation of Vietnamese refugees who had settled in the UK, the country that had been my home for almost ten years. In March 2020, the BBC screened Whatever Happened to the Boat People?. Presented by therapist Rachel Nguyen, it encouraged me to deepen my research. I took comfort that I wasn’t the only one who was curious, who thought this marginalised history merited attention.

Libraries were still closed due to the pandemic, so I had to rely on my computer. Thankfully, the National Archives have a wide catalogue of digitised documents, and I was able to see, if only a little, Vietnamese people’s part in Britain’s history. There were the meetings that Margaret Thatcher had held as prime minister, the letters she had sent and received on the Vietnamese refugees. I saw a video of Princess Anne visiting the Ubon camp in Thailand, walking through the nursery and pouring milk into the cups of curious young children. I read record after record which concerned the British Vietnamese diaspora, sometimes only in passing, but it was proof that this community of refugees still existed, that they were here.

“All these emotions mingled in me: feelings of distress and hopelessness, of anger and grief, but for who or what I wasn’t sure. Slowly, tentatively, I began typing them out of me”

As I was conducting my research, the news cycle remained relentless. Crimes against East and Southeast Asians were still increasing. Reports of the Syrian and Afghanistan refugee crises showed a dire situation that made me realise how, in 50 years, little has changed for vulnerable people fleeing violence. All these emotions mingled in me: feelings of distress and hopelessness, of anger and grief, but for who or what I wasn’t sure. Slowly, tentatively, I began typing them out of me.

Writing my novel Wandering Souls was a way for me to express these complex feelings, and to get closer to my family heritage and my Vietnamese roots. It was a way for me to digest the history that held me, and to prove myself into existence. And I hope that it shines a light, if only a flicker, on the British Vietnamese diaspora in the UK, who have been in the shadows for too long.

Wandering Souls by Cecile Pin is published by 4th Estate on 2 March

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.