Recently, mental health awareness has boomed – with campaigns like Time to Change and Project Semicolon making mental health a more acceptable, if still fairly unpalatable, topic. But, while depression and anxiety are being discussed more than ever before in everything from newspaper articles to viral social media posts, are other – more acute – conditions being overlooked? Prevalence potentially creating this dichotomy of mental health issues seems an obvious cause, but this is not the case. Statistics show that depression affects 2.6% of individuals, anxiety 4.7%, and a mix of the two 9.7%, while personality disorders affect 3-5%.

Perhaps the reasons for emphasising certain mental health issues over others are more socially insidious. One reason may be the differentiation that exists between symptoms and disorders: there’s a level of comfort in discussing the former, especially those many experience at some point in their lifetime, or that can be related to (e.g. depression as extreme sadness, anxiety as extreme panic). Disorders differ, being far more pervasive in affecting the way the brain filters and processes information, as well as actual patterns of thinking.

Not only is this more difficult to immediately educate on, there’s more stigma; it becomes harder to follow the commonly-expressed adage of someone “not being their illness” when the disorder affects – or, in fact, comprises – a large part of their personality. Quite simply, symptoms are “easier to swallow” than disorders. And in the same way that the media favours “safe” depictions of minorities, with light-skinned POC and not-too-flamboyant queer people, it favours “safer” depictions of mental health. In a society that functions largely on the privilege of some above others, perhaps we should not be surprised that privilege disparity extends to mental health issues.

While accessible information is thinner than I’d like for all ten different types of personality disorder compared to common conditions, I hope to clarify a little on one in particular: Borderline Personality Disorder. Before continuing, I must point out that my experiences and opinions, while representative of my mental health and life experiences, do not represent all BPD sufferers. With 9 diagnostic criteria and 256 combinations of said criteria, every individual with BPD is different, with different experiences.

What is borderline personality disorder?

Personality disorders, generally, are conditions in which a person is significantly different from average (regarding thought, perception, emotions, or ability to relate to others). There are several different types, including borderline, paranoid, and antisocial, amongst others. The symptoms vary greatly, but virtually all entail issues with distorted patterns of thought and emotion processing. For me, it’s somewhat like having a PC brain in a Mac world – both computers function, but with completely different systems. I perceive things differently, I react to things differently, and my abilities will often differ from what’s expected by most. Neurological and processing differences are documented: for example, the emotion regulation centre is weaker, and there’s an increased ability to notice subtle facial expressions, although neutrality is sometimes misinterpreted as anger.

The term itself originally referred to the idea that sufferers were on the borderline between neurosis and psychosis. This is now considered inaccurate, and has led to other terms being used as well, like Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder, and Emotional Intensity Disorder. However, in my opinion, the original idea – if undeveloped – wasn’t as far from the truth as one might think. BPD sufferers deal with typically “neurotic” issues, like depression and anxiety, but the things that trigger them or the extent that they do could certainly be considered close to delusional – or borderline psychotic. This is not to trivialise conditions in which psychosis plays a larger part, but the magnitude of distorted thinking (and the fact that sufferers may experience full-blown psychotic episodes as a symptom of the disorder) suggests some level of psychosis. Because of this, I use the term ‘Borderline’; others may use the terms above, but all describe the same disorder (though differently worded according to diagnostic manual).

Other co-occurring disorders are very common (including depressive disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorders, amongst others), which can further complicate treatment as more than one type of therapy or medication is required.

What are the symptoms?

The criteria includes 9 symptoms:

- Fear of abandonment

- Very intense emotions

- Uncertainty around identity

- Difficulty in making and keeping stable relationships

- Impulsive actions

- Suicidality and self-harm

- Feelings of emptiness and loneliness

- Issues with anger management

- Paranoia, psychosis, or disassociation

(It’s essential to point out that experiencing most of these things individually at some point during one’s lifetime is normal; the difference with BPD, however, is that it involves the sufferer experiencing at least 5 of these symptoms for some time.)

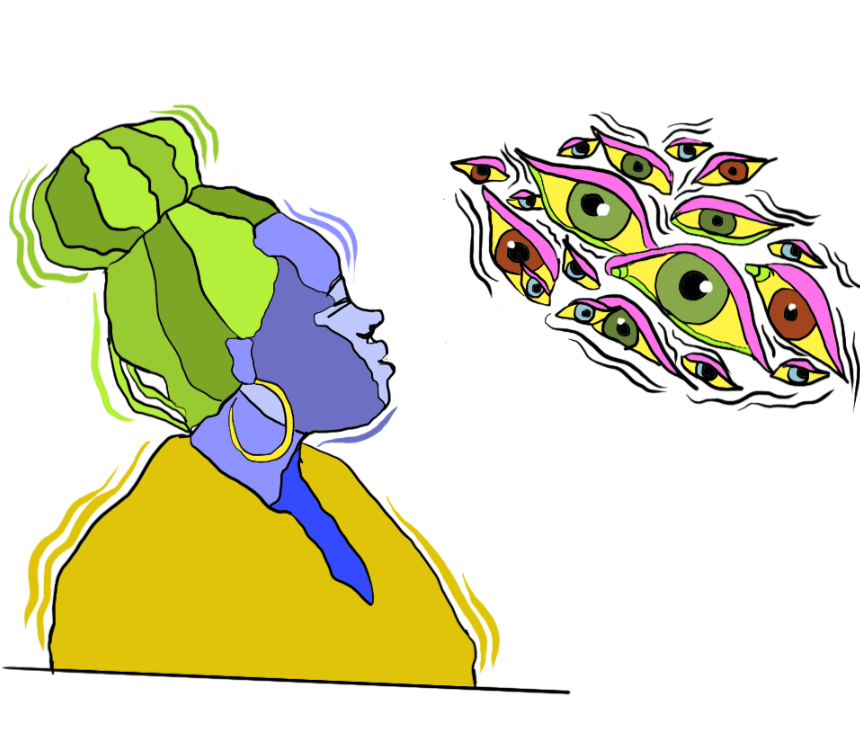

For me, the intense emotions are one of the most pervasive aspects. As discussed, reactions are different to that of the average person, which makes happiness more like joy; sadness, deep depression; anxiety, a very panicked state; irritation, anger; and embarrassment, shame. Simply put, feeling something mildly is rare. Any emotion registered tends to be a strong one and – thanks to a lack of emotional resilience – can make a large impact, though it might outwardly seem trivial. Marsha Linehan, who created the most successful BPD treatment, described BPD sufferers as the psychological equivalent of third-degree burns patients, with no emotional skin. She added:

Even the slightest touch or movement can create immense suffering. Yet, on the other hand, life is movement.

Borderline Personality Disorder has also been described as living with constant emotional pain, and the resulting attempts to deal with it. A fair assessment in my opinion; BPD is pervasive, long-lasting, and treatment-resistant, and brings suicidal urges. Because suicidality is a key aspect of BPD, it has a higher mortality rate than most mental health issues; this is, for me, the main reason it requires more awareness and addressing. With a suicide rate about 400 times that of the general population, people with BPD have a condition that is rarely thought of as life-threatening, but most certainly is.

Borderline Personality Disorder and me

Whenever I hear someone say “I wish I could be happy like before”, I’m always filled with a sort of sick envy. BPD has always been a part of my life, and I remember specific moments that I now would attribute instantly to my diagnosis, but at the time were seen as the sensitivities of a child.

The increasing severity and ability to fully articulate what I was feeling led to me being referred to the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Team when I was 12, and began antidepressants at 13. Although I developed fairly identical symptoms to now, personality disorders are rarely diagnosed before 18, so I spent several years being unsuccessfully treated for anxiety and depression. As you can imagine, with this type of longstanding illness, a certain bitterness is inevitable, and it has only worsened with time. Experiencing your own mind hamper most of your biggest opportunities is a difficult thing to stay positive in the face of, and my inability to mask that pain lost me friends, family, and significant others.

I finally received my diagnosis of BPD about a year ago. A first step for sure, but a first step on a long road, and after five suicide attempts and two detainments under a section, it felt long overdue. Adding insult to injury, treatment for BPD takes years, and even getting that treatment is a fight. I was only recently put on a waiting list for specific personality disorder treatment, and have been told my initial assessment will be ‘in 2017’. Considering how much effort was put into even getting that far, I can’t help but wonder how many others’ mental health – and lives – are at stake as a result of a lack of available treatment and accurate diagnoses.

*

Ultimately, the general growing mental health awareness is a blessed thing. It’s simply a matter of extending the discussion. Let’s talk seriously about depression and anxiety, but also about personality disorders (and OCD, and schizophrenia …)

Just as in other discussions that favour inclusivity, we can adapt and expand to make sure all the important topics are covered.

After seeing the (what was once known as) “gay” community become more inclusive to trans people, and more recently, those who don’t fit the binary, and feminist community become more intersectional with regard to trans women and women of colour, we know we can always do more to make sure everyone is represented within an oppressed community of people.

As an often silenced community, those affected by mental health are being more heard by the wider world than ever before – I hope you’ll help in lending a few voices.