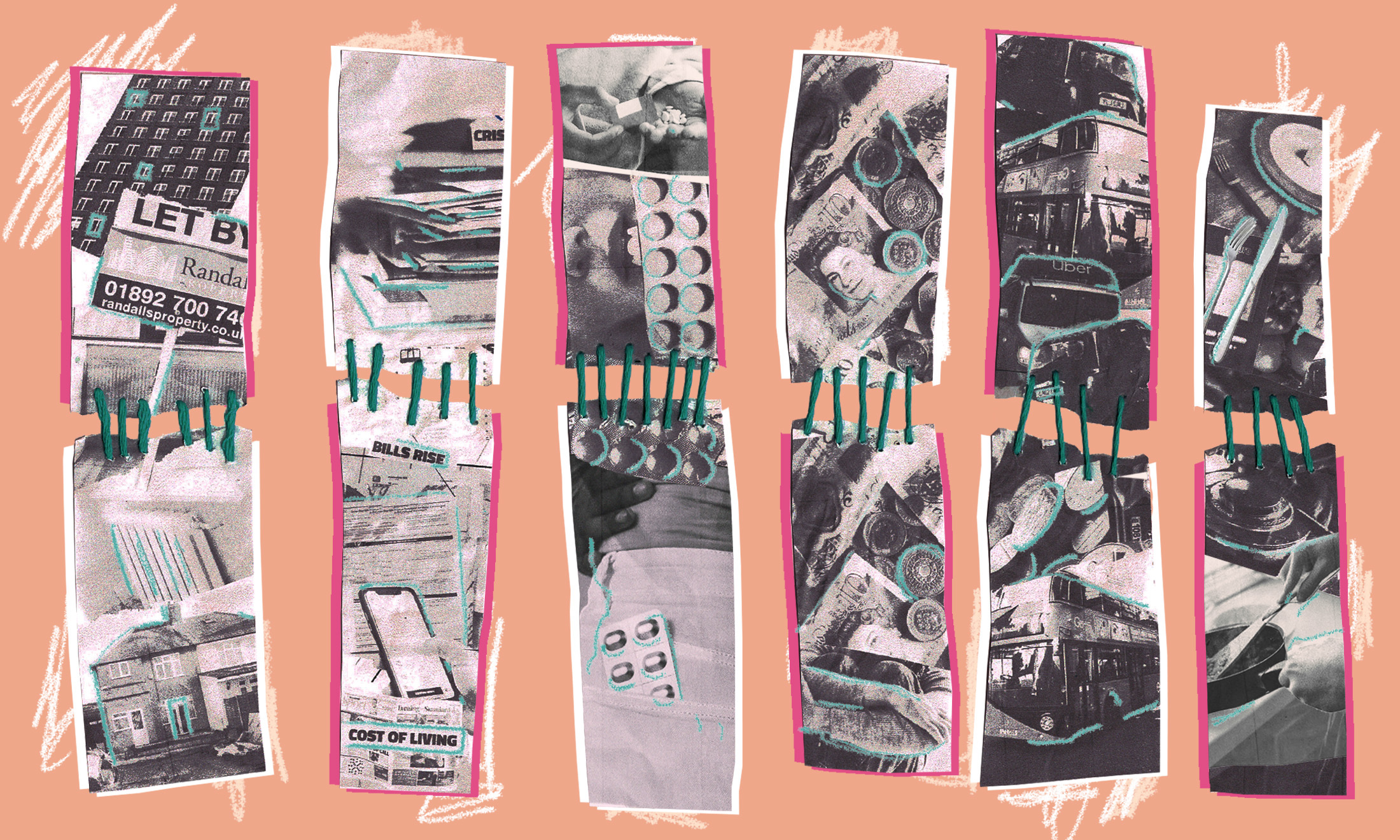

The cost of living crisis risks becoming a suicide crisis. What might keep us alive?

Psychologist Dr Sanah Ahsan looks at what might give us the hope we need to survive in an increasingly unliveable world.

Sanah Ahsan

18 Oct 2022

Aude Nasr

Content warning: This article contains mentions of suicide.

The cost of living crisis is impacting all aspects of our lives, from renting and dating troubles to soaring energy bills and food prices. gal-dem is publishing stories exploring our communities’ experiences during this tumultuous time – and what we can do to collectively work towards a fairer future.

The UK’s cost of living crisis risks becoming a suicide crisis. Charities are reporting an exponential rise in suicidal calls. “Money worries” are leaving children as young as seven wanting to die, and teenage suicide rates are the highest they’ve been for 30 years. Many adults can’t sleep from financial stress, can’t afford to eat, socialise or heat their homes. All this while the government gambles with an already perilous economy, removes life-saving caps on energy prices over the next two winters, and tells us to find better jobs if we can’t afford our astronomically high bills.

How can we expect anyone to survive these unliveable conditions? For some, suicide may feel like the only available escape: a fire-exit from a society ablaze with oppression.

Yet, the story told about suicide is that it’s a self-inflicted, tragic one-off incident, a result of an individual’s mental health crisis. As a psychologist, I’ve seen how mental health services render the problem and solution as being within a psychologically damaged or “disordered” individual, overlooking the madness-inducing conditions of austerity and oppression. People who are suicidal and have a low-income are more likely to be medicated, and suicide prevention guidelines recommend reducing access to suicide methods like painkillers or sharp objects. But none of this actually addresses what’s making us want to die. Services may (just about) be keeping people alive, but how ethical is that when we’re doing nothing to change unliveable conditions?

“Services may (just about) be keeping people alive, but how ethical is that when we’re doing nothing to change unliveable conditions?”

Of course, the cause is not just poverty. It would be simplistic and unfair to impose a single explanation onto anybody’s exit from this world. We also can’t deny the global evidence that tells us violent austerity policies lead to more people taking their lives. The 2008 recession caused a sudden spike in UK suicides. Greece’s suicide rates rose by 60% through their economic crisis. Suicide rates are rising in Pakistan, with floods causing economic suffering and damaging livelihoods. Farmers in India are lost to suicide every eight hours because of debt and the climate crisis devastating their work. Yet, professionals continue to prescribe antidepressants with side-effects that can increase suicidal feelings, and do nothing to alleviate the root cause.

As more people die by suicide in the UK during this cost-of-living crisis, will we simply say they were ‘mentally ill’? Or will we question if they died at the hands of racism, poverty and violent austerity? Especially as it’s racialised communities who are at increasing risk of suicide. We’re twice as likely to be in serious debt than white people, most vulnerable to loan sharks, and most likely to be isolated and lonely. But ethnicity data for suicides has not been properly recorded. Plus, stigma attached to suicide in racialised communities means under-reporting is common, so we don’t actually know how many racialised people are dying this way.

“We can’t deny the global evidence that tells us violent austerity policies lead to more people taking their lives”

Cultural perceptions of suicide have followed a questionable trajectory: deemed to be a sin against god, an illegal act and a psychological disorder. These attempts to push suicidal feelings into the shadows might reflect society’s fearfulness of any extreme expressions of despair. So, what if we were to have a less fear-driven, individualised and moralistic view on suicide?

This is a hard ask. Having lost loved ones to suicide, and experienced wanting to die myself, I know how emotive this subject can be. When faced with someone who is suicidal, we’re forced not only to stare death in the face, but to feel our own powerlessness, misery or guilt. This isn’t easy, nor is it our fault.

“What if we were to have a less fear-driven, individualised and moralistic view on suicide?”

But compassion is crucial. We need to make it easier to talk to each other about wanting to die, rather than robotically using tick-box questionnaires like “Do you have a suicide plan, or sharp objects at home?” It means allowing ourselves to be witnessed in our understandable (and messy) despair, and holding each other with love and kindness. Through talking about what’s causing our pain, we not only learn to bear the complexity of suffering, we build trust, interdependence and break down stigma.

Crisis response isn’t easy. Sometimes, we’re desperate to bypass the hurt we feel at living in these violent systems. But learning to feel how pain shows up in our bodies helps us develop a more intimate and compassionate relationship with it, birthing greater choice and agency. This collective practice might be supported by chosen family, community, land, ancestors, therapists, medicines, prayer and support services. Collectively, our pain becomes a compass pointing us towards the structures of domination that need to change.

“Suicide prevention must have social action at its centre”

Suicide prevention must have social action at its centre. Cash transfer programmes could be life-saving right now, like the Brazilian Bolsa Familia programme which reduced suicide by 61% through financial aid over an 11-year period, ending in 2015. Economic and housing insecurity put us at greater risk of substance use, alcoholism, neglectful parenting and domestic violence – all of which make it harder to stay alive. This is why there are huge psychological benefits of implementing Universal Basic Income and secure housing.

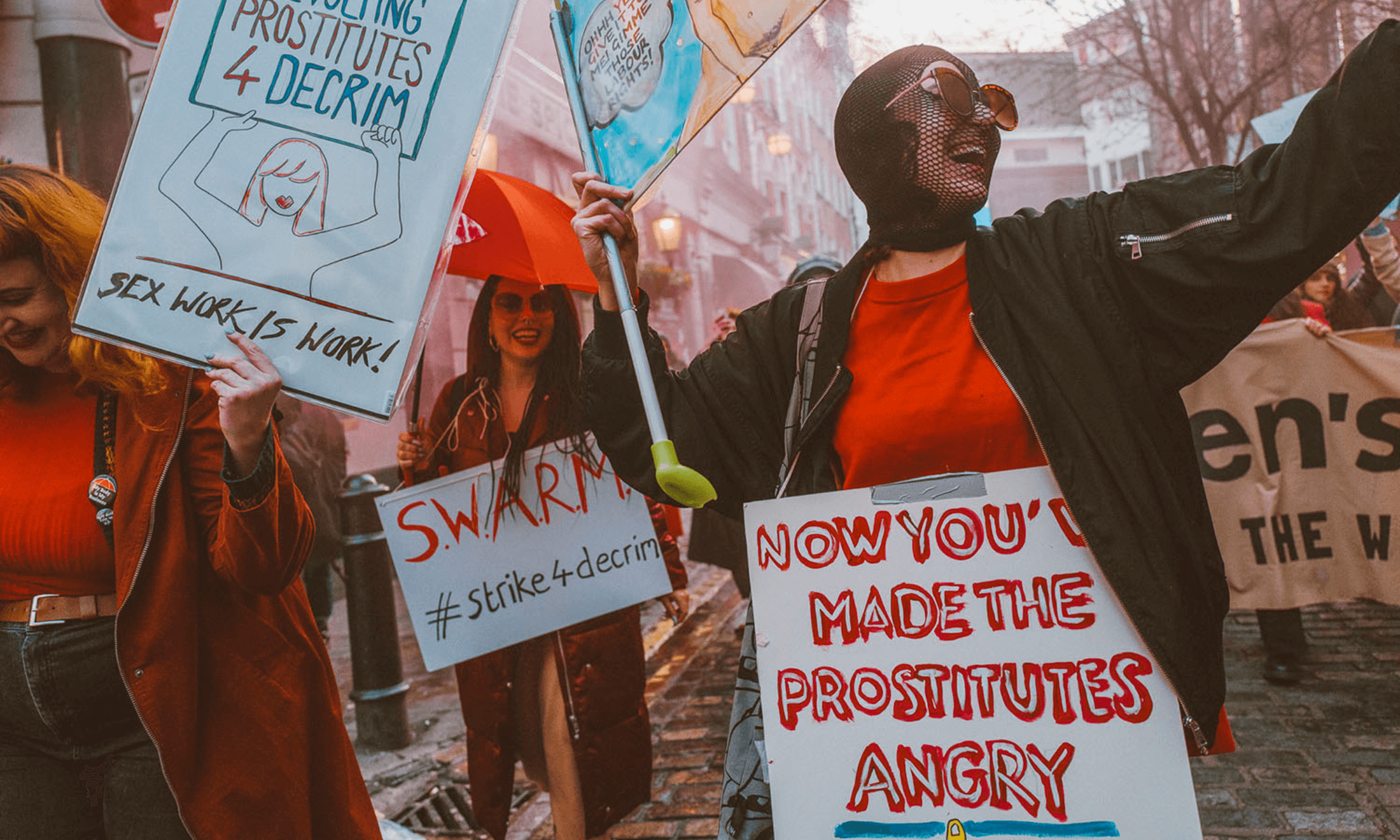

Change is already being mobilised by groups like Don’t Pay UK, Enough is Enough and People’s Assembly – organisations which are campaigning for decent housing for everyone, slashing energy bills, ending food poverty and taxing the rich. Though these campaigns don’t explicitly mention suicide or mental health, they support suicide prevention through crafting conditions for more liveable worlds.

The UK suicide researcher China Mills reminds us that “suicide is about social justice. There’s government culpability in creating conditions that make people’s lives unliveable. For example, the systematic dehumanisation of folks who claim benefits and experience poverty, as being ‘burdens’ on the economy.” China runs the Deaths by Welfare project at Healing Justice London, which is co-designed by people with lived experience. It evidences untold numbers of disabled people who’ve died by suicide due to state violence. Some wrote suicide notes naming the Department for Work and Pensions, protesting murderous “fit for work” assessments and benefit sanctions. Even amid such devastation, the project unveils stories of rallying, resistance and collective power by groups like Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC).

“There are profound psychological benefits that come when oppressed people gain a sense of their collective power”

There are profound psychological benefits that come when oppressed people gain a sense of their collective power, as evidenced by the Egyptian revolution to trade union solidarity in Poland. Social action gives us a sense of purpose, connectedness and community, helping alleviate some of this state-enforced isolation, shame and misery. Yes, our hearts are smashed under the crushing weight of state violence, but can we (as the Indian author Arundhati Roy invites) still rally our fragments?

This returns us to the question: what might keep us here? Death can’t be our only exit door. Through dismantling systems that are anti-life, we might live with more pleasure, safety and connectedness. Loving (and therefore therapeutic) conditions help make this possible: like secure housing, financial aid programmes and UBI, affordable living, abolishing benefit sanctions, community organising and trusting relationships that can hold our despair.

Beyond survival, we deserve freedom and joy. We can’t allow the cost of living to become life itself. The lives of the most marginalised in our society are not disposable. Every one of us is inherently sacred, not just the tiny minority at the top. Our lives must be valued. It is survival of the nurtured, not survival of the fittest. We need each other. We have a greater chance of keeping each other here if we make this world a more liveable place to be.

Life is hard. Tending to our pain is a practice we can cultivate regularly in community – not only as a crisis response. Here are some groups, organisations and resources that centre justice in their frameworks of healing:

Decarcerating Care resource library

Stop Suicide NENC Cost of Living crisis resources

Madness and Oppression publication by The Icarus Project NYC

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or you can email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org

Text SHOUT to 85258 from anywhere in the UK, anytime 24/7, about any type of crisis, including suicidality.

In the US, TrevorLifeline, TrevorChat, and TrevorText provide LGBTQ+ crisis support. If you are thinking about suicide and in need of immediate support, please call the TrevorLifeline at 1-866-488-7386 or select TrevorChat below to connect with a counsellor.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.