Photography courtesy of Lime Pictures, BBC, ITV, and Fremantle

British soaps taught my immigrant parents about their new home

How do you learn about a place when you've just landed? For my parents, they turned to the tumultuous storylines of trash telly to see what the UK was about.

Asyia Iftikhar

14 Feb 2020

Picture this: a family of four for whom the past year has been tough. The McAllister’s found new challenges, fiery affairs, property feuds, sexual awakenings and plane crashes are just the tip of the problems that have troubled their Yorkshire hometown. This might seem like terrible luck for a small town in the middle of the North of England. A place where the vowel in bath sounds like the one in “math” rather than the one in “scarf” and thick regional dialects roll across the town’s fields. But for Emmerdale, a fictional place full of fictional people, this was their normal.

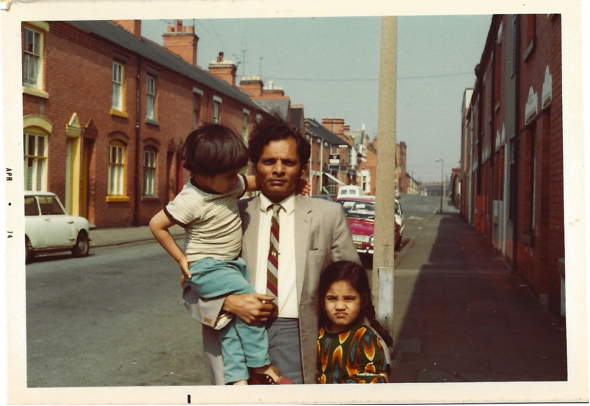

In 1993, the same year as the fictitious Beckindale Air Disaster, my mother stepped off a Pakistan International Airlines plane with her one-year-old daughter and arrived in Sheffield, UK. A few months earlier, my father arrived. For the first 30 years of their lives, my parents had lived in large and vibrant cities and communities, surrounded by extended family in a culture they knew better than themselves. Sheffield, with its rainy roads, majority white population and steely British reserve, was a bleak comparison.

Daytime soap operas are extreme shows for mundane days and a stalwart of British television. For my parents, these episodes formed the bedrock of their knowledge of Yorkshire society in the early 1990s as they navigated their new lives after immigrating from Pakistan. My parent’s accents and perfect classroom English clashed harshly with the northern slang and thick accents nestled on the other side of the spectrum. As doctors, trying to build a relationship with their patients and colleagues, it became apparent they would need to adjust quickly; it seemed to be the natural solution to pick up the native touch their language lacked.

On 1 January 1951, The Archer’s aired to the nation, precariously toeing into British hearts to see if it could find a home there. Almost 70 years, 1000s of episodes and more plot twists than you could count later, its charismatic theme tune is known to most who hear it. However, this style of shocking drama, following the trials and tribulations of everyday people in the most terrible circumstances set off a British TV revolution, with new soaps airing almost constantly over the next three decades.

Coronation Street, Emmerdale, Brookside and Eastenders were all soon household names. These were not the type of show that you would start watching from season one episode one, but to dip in and out as they created their legacy. There was a fascinating compulsion to see the rise and demise of a character or plot that had been so carefully woven over five years, fitting into a complex multilayered world and viewers are just the fly-on-the-wall. Then to keep you hooked, soap operas would make their melodrama palatable by reflecting the woes of the population. Infidelity, destitution, family bust-ups, and boredom. In the 1980s and 90s, Brookside, set in Liverpool, subtly made remarks on the pain of Thatcher’s government on northern working-class people. Through shared experience, the characters in these shows almost became part of the family and held a funhouse mirror up to British society.

In Pakistan, England had been the coloniser that had ruined my parent’s homeland, so moving to the country that had performed such personal atrocities was never going to be easy. My mother remembers those first few years where my father consumed all the media he could, becoming better versed in local lingo and his ears tuning in to foreign accents. He partly attributes his quick ascension through his medical career to his understanding of culture and language through trash telly.

“You could see how people greeted each other, how they lived”, he tells me. What seemed the most insignificant part of the dialogue – two people simply saying hello – became as precious as the plot. The shows often portrayed the most extraordinary events, it painted a sometimes nasty picture of Yorkshire and how society stretched his own limits of what he deemed acceptable. One of my father’s culture shock memories from the year he arrived was the case of James Bulger, a toddler, murdered by two 10-year-old boys in Merseyside. This case shook the nation, and as my mother was preparing her own journey over with their one-year-old child he spoke of the fear he felt adjusting to this country without a support network. He makes it clear that he wasn’t naive, of course, he understood that the horror portrayed in these shows was exaggerated for entertainment purposes, but as is the case for these types of shows, they were always based in truth.

“For the past 27 years, soaps have been able to connect to our family through grief and joy in our average days and to communities who once felt out of reach without any of us realising”

My mother found herself in the middle of a hectic life, with three children, a full-time job, a sparse community and household duties. When she first arrived in the UK she found a mindless escape in Eastenders, a soap opera set in the East end of London, Home and Away and Neighbours (both Australian-based). Soon, her time became limited and she chose to keep Neighbours as her regular 30 minutes where no one could disturb her and she could lose herself in the dramatic goings-on of Ramsay Street. For the past 20 years, I have grown up watching Neighbours with her, so much so that it’s now become the main part of our bonding. To my mum and I, we know Margot Robbie as ‘Donna’ from Neighbours, and Chris Hemsworth as the rival star in Home and Away.

We’re sitting in the living room on our third set of sofas, a new rug and TV in the past 15 years since we moved here; the framed photos of my Nano and Nanaboo are placed pride of place by the door. Our cat lies next to me which is symbolic as the last time our family had owned a cat was when my grandmother was living in India before the partition. The house is a collection of idiosyncrasies connecting the threads of my two cultures.

“It’s a show where they care for each other, try to own up to their mistakes and some characters I have been watching grow for the past 25 years,” my mother says. Two years ago Shane and Dipi Rebhecci moved to Ramsay Street and there was a real sense of excitement; this was one of the first brown families to become regulars. One of the plots followed a character dealing with racism which prompted us to open up discussions about the casual racism we had suffered in this country and how we became accustomed to brushing it aside. When Aaron and David became the first gay married couple of Neighbours, my mother asked me about the LGBTQI+ community; this was the first time we had spoken about this taboo topic in my entire life. Since then, there has been great representation for the LGBTQI+ community including a transgender woman, Mackenzie.

For the past 27 years, soaps have been able to connect to our family through grief and joy in our average days and to communities who once felt out of reach without any of us realising. While they may never see the same popularity they saw in their post-war heyday, whatever their future their enormity cannot be understated.