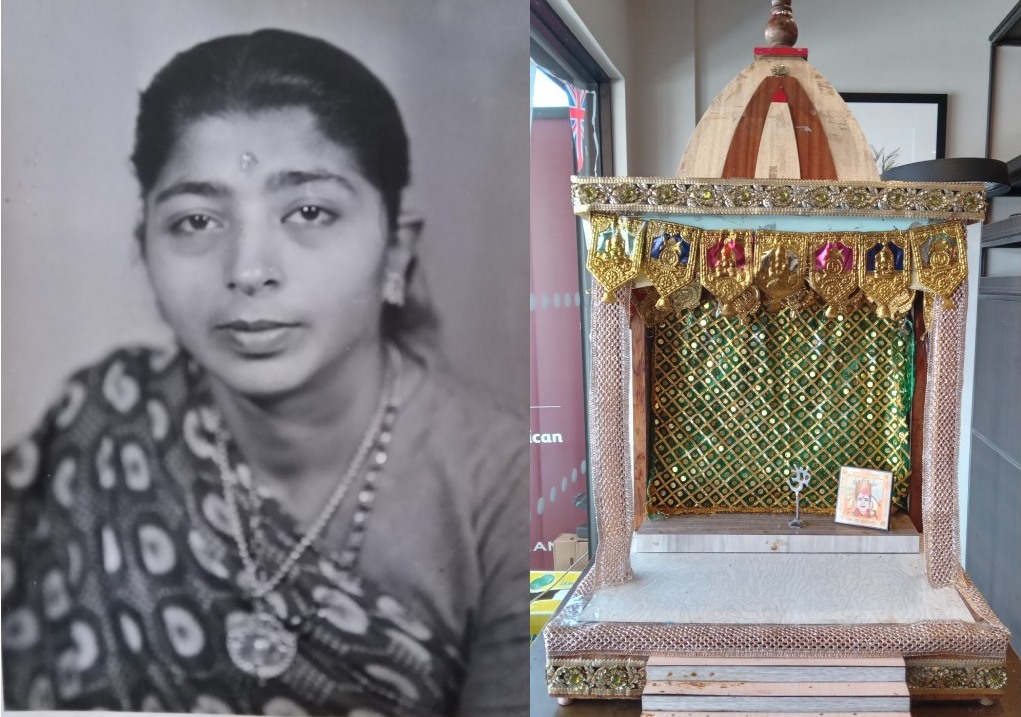

Nisha

How Ugandan Asians are keeping their history alive, 50 years after expulsion from their homes

The forced expulsion of Asians from Uganda in 1972 is still raw for many. Half a century later, they share how the anniversary helps keep their history alive, and how they made UK cities like Leicester their home.

Mansi Vithlani

04 Aug 2022

Editor’s note, 26 October: Following feedback post-publication, this article underwent a sensitivity read in September 2022. In this exceptional circumstance, we felt it appropriate to make the changes suggested by the reader to the text. The updated version is below with factual changes listed at the bottom of the article, and a link to the previous version of this article is available here.

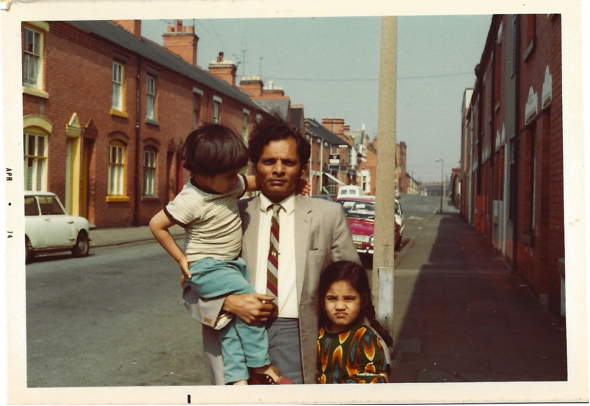

“I’ll never forget my mum and dad losing me at the airport,” says Nisha. She was only four years old when Ugandan army soldiers snatched gold wedding jewellery from her mother’s neck and wrists, witnessing the anguish as government officials stripped their belongings – and identity – away. It was lucky the family ended up reuniting just before boarding their plane from Kakira, Uganda to the UK in October, 1972.

“My family had to leave their home and couldn’t even bring any savings, just a suitcase full of clothes and £50 in cash,” says Nisha, who preferred not to use her last name in this interview, and whose family settled in Leicester. “They didn’t speak English. It was like starting all over again in an alien country.”

August 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the Ugandan Asian expulsion in which the dictator Idi Amin gave Asians of Indian descent just 90 days to pack up their lives and leave the country. Amin, who ruled as Uganda’s third president from 1971 to 1979, is regarded as one of history’s most cruel dictators. After seizing power in a military coup, he ordered the removal of Asians living in Uganda, accusing them of engaging in unethical business practices and ethnic elitism, and threatening to send those who stayed to concentration camps.

More than 60,000 Asians were expelled from Uganda between August and November 1972, many of them with British passports moving – after some international pressure was put on Britain to accept them – to the UK. According to the Home Office, roughly 27,000 Asians with British passports settled in cities like Leicester, Birmingham, Manchester and London, where communities of Ugandan Asians have since thrived.

Five decades after they were forcibly exiled from their homes amid conflict and violence, Ugandan Asians in Leicester – home to the UK’s largest Asian population – are not only reflecting on the effects of the expulsion and coping with the trauma it caused, but also looking ahead to the future of their community.

The expulsion

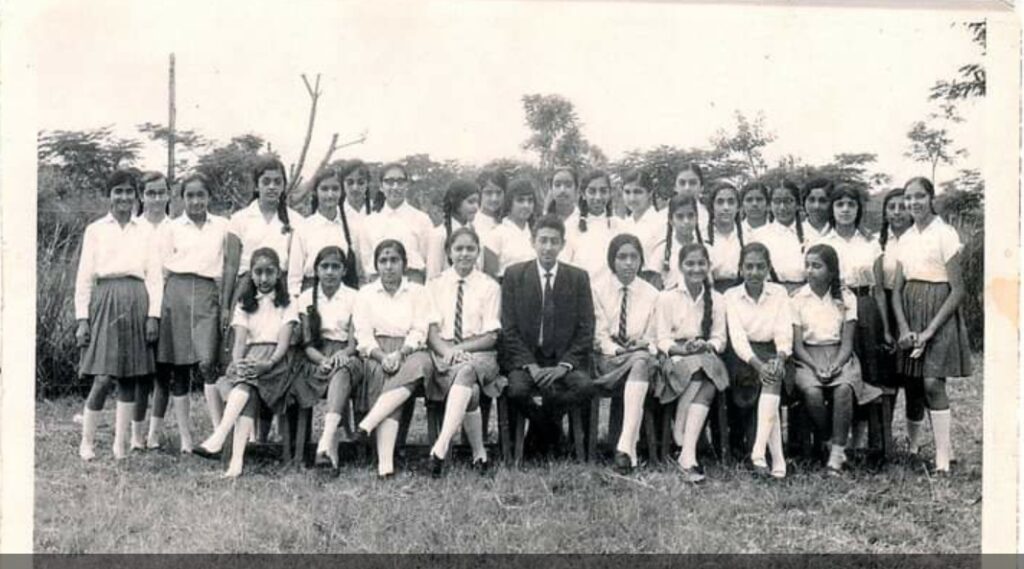

From before the end of the 19th century, people from India (at the time under British colonial rule) had been moving to East Africa at British instigation. Fast forward a generation, and – encouraged by the favourable policies the British imposed for South Asians – many had stayed and had families. Asians were allowed to trade, the local population were not. Although Asians made up just 1% of Uganda’s population, they earned one fifth of the nation’s income.

The British had also invested in the education of the Asian minority over the education of Ugandans, and schooling and healthcare were racially segregated under colonial control. The Asian community in its living, social and economic spaces were often completely isolated from the local (and British) population. After Uganda gained independence in 1962 and the British rapidly departed, racial, social, and economic tensions between the Asian population and the local population increased.

By the time Amin took power, matters had soured significantly. Neighbouring Kenya and Tanzania had already imposed severe economic and trading restrictions on Asians that had caused many of them to flee. Uganda took the more drastic step of ordering them to leave. Amin blamed Ugandan Asians for destroying the country’s economy and promoting corruption. Upon announcing the expulsion, he claimed he was “giving Uganda back to ethnic Ugandans”.

The escape was incredibly traumatic for some, forcing them to leave behind the lives they had built. Due to my own familial connections to the exodus, I was inspired to learn more about the event for a university project in 2022. My objectives were to gather untold tales, explore feelings of disconnect from Uganda, and examine how childhood trauma might affect an adult’s life.

84 Ugandan Asians aged between 50 to 80 living in Britain responded to my survey, alongside some of their children and grandchildren who responded on their behalf. The research indicated that 74.7% of Ugandan Asians still suffer from trauma, with their adulthood plagued by undiagnosed PTSD, such as flashbacks and nightmares that are common among those who have undergone traumatic experiences as children.

“On the way to the airport, there were roadblocks with checkpoints, with the soldiers saying to my mum: ‘Give us your jewellery’,” said one anonymous respondent. “She hesitated, they pointed a gun at my father and said: ‘Him or the gold’.” Being smuggled on buses, hiding under passengers’ legs, and escaping local authorities are several experiences that respondents outlined, with the grief passed down to the next generation.

“I didn’t know where I was going, what I would do in a new country. I had no experience of leaving Uganda before”

The BBC reported that the first 193 Ugandan Asians arrived at Stansted Airport on 18 September 1972. Some escaped Uganda before Amin’s announcement – Ramnik Varu, now 76, was among them.

Amin fired Asians from roles in trade, commerce and particularly in educational sectors. These policies meant Ramnik lost his role as a teacher. Ramnik, classed as a British national but not as a British citizen, travelled from Uganda to Yugoslavia, where he was temporarily lodged in a detention centre, and eventually settled in Leicester.

“I didn’t know where I was going, what I would do in a new country. I had no experience of leaving Uganda before,” he says.

For those like Ramnik, who remained in Leicester, there’s a sense of pride for building lives and livelihoods over the last 50 years.

“We brought skills with us, and those skills are sitting on the Golden Mile,” says Mina Patel, who moved as a child along with her family in 1972. She’s referring to the famed Belgrave Road; a stretch of shops home to gem-filled jewellery stores, filled with the scents of incense drifting from the doorways of boutiques and saree emporiums. Here, you’ll also find tropical fruits and vegetables, and thirst-quenching coconuts alongside masala chai stalls and iconic eateries including Bobby’s restaurant. The Golden Mile is often referred to as “Little India”, providing the many home comforts missed by those who migrated.

Arriving in England

Despite what the Ugandan Asian diaspora have achieved today, Mina’s move to Leicester – and the experience of many others like her – was not what she had hoped for.

Before Mina arrived in England in October 1972, Leicester City Council launched a campaign to actively discourage Ugandan Asians from moving to the city. The city already had a large immigrant Asian population (including from Kenya and Tanzania) and thousands of families on the council’s waiting list for accommodation. Schools were overcrowded and social services overwhelmed, creating an anti-immigrant sentiment. Yet 10,000 survivors chose to settle there.

Upon moving, Mina’s mother wrapped their family Mandir (a shrine often found in Hindu homes) in sarees and sent it by mail from Uganda to Medway Street, Leicester, but it never arrived. Exactly 10 years later, to her surprise the trunk was delivered to her new address in 1982. Only the Mandir was inside the trunk – the sarees had been stolen and replaced with newspapers.

“My mum came to pick me up. The next morning these little boys as I arrived in the playground, all huddled up and said, ‘Did you see what she wore? We don’t wear sari in this country’,” Mina says.

Racism was not just limited to the playground. At the time, vegetarian options for school dinners were scarce and Mina was only provided with meat, which she refused to eat, having grown up vegetarian due to religious and cultural reasons, common among many Hindus. “The dinner lady called the headmistress who said ‘there’s no other choice for you, and don’t you dare bring your religion in my country’,” she explains.

Every day since that incident, Mina took the hour-long journey to her home for lunch, ate, and then returned to school. In order to support the expanding Asian community in Leicester, her grandparents opened Bobby’s supermarket, the first Indian grocery shop in the city.

“Many exiled Asians have never returned to Uganda due to the trauma”

Looking back, Ramnik believes the expulsion was a blessing in disguise. Before retirement, he spent 20 years teaching music in Leicestershire and helped his son launch their successful family business Spicentice. He feels the expulsion allowed Ugandan Asians to start a life in the UK that was challenging, but full of opportunity. “Although I am proud I was born [in Uganda], what can I do there? The UK is my home,” he says.

Many exiled Asians have never returned to Uganda due to the trauma. My research found that 50.6% of those expelled missed Uganda, while the other half had no desire to return.

‘We have so much to learn’

Fifty years have passed since Ramnik and others from the community moved to the UK, but in many ways it feels like little has changed for those seeking refuge here. The government is pressing through the Nationalities and Borders Bill, which makes it even more difficult for refugees to seek asylum in the UK, and dual national citizenship may be revoked by the government without warning. “I think immigrants that come to this country now have a really hard time and there is a lot of negativity,” says Nisha, who is now 55, based in Leicester. But in this environment, to commemorate the exodus and reflect the tolerance of the community, many Ugandan Asians are creatively preserving their heritage through creating art inspired by these experiences.

In early August, Leicester’s Curve is staging Finding Home: Leicester’s Ugandan Asian Story at 50 to commemorate the historically significant year for the city. Pieces by local playwrights include Chandni Mistry’s Ruka, based on a video game for families and children where a child discovers her mum’s past, Dilan Raithatha’s Call Me By My Name, which explores themes of self-identity, and Ashok Patel’s Ninety Days, a play set during the expulsion in which two couples must confront the reality of Amin’s order as the 90-day deadline draws closer. The families of each playwright all settled in Leicester from Uganda as a result of the expulsion.

“This isn’t just about South Asians, this is about British South Asians. We aren’t separate. We are part of the fabric of society”

“I’m not trying to tell the stories to the people it’s already affected. This is about the opportunity to fulfil other communities who didn’t know these experiences even existed,” says director of all three plays, Mandeep Glover. “This isn’t just about South Asians, this is about British South Asians. We aren’t separate. We are part of the fabric of society.”

To inspire the stories, the Curve organised several public gatherings with Leicester’s Indian community to recall their journey to the city, in a comforting setting over a cup of chai. Both Dilan and Mandeep recall that initially older community members were hesitant to share their stories.

“We asked them why they were reluctant to talk to us at the start. ‘Why don’t you share this with your children? Why didn’t you write something from your own words?’ And they said, ‘no one cares about us anymore,” says Dilan, whose paternal family were expelled by Amin.

Both Dilan and Mandeep are grateful that the trust is reciprocated from the Ugandan Asian community to tell their story. “[The play is] not for five-star reviews,” says Dilan. ”It’s just about getting this community shown.”

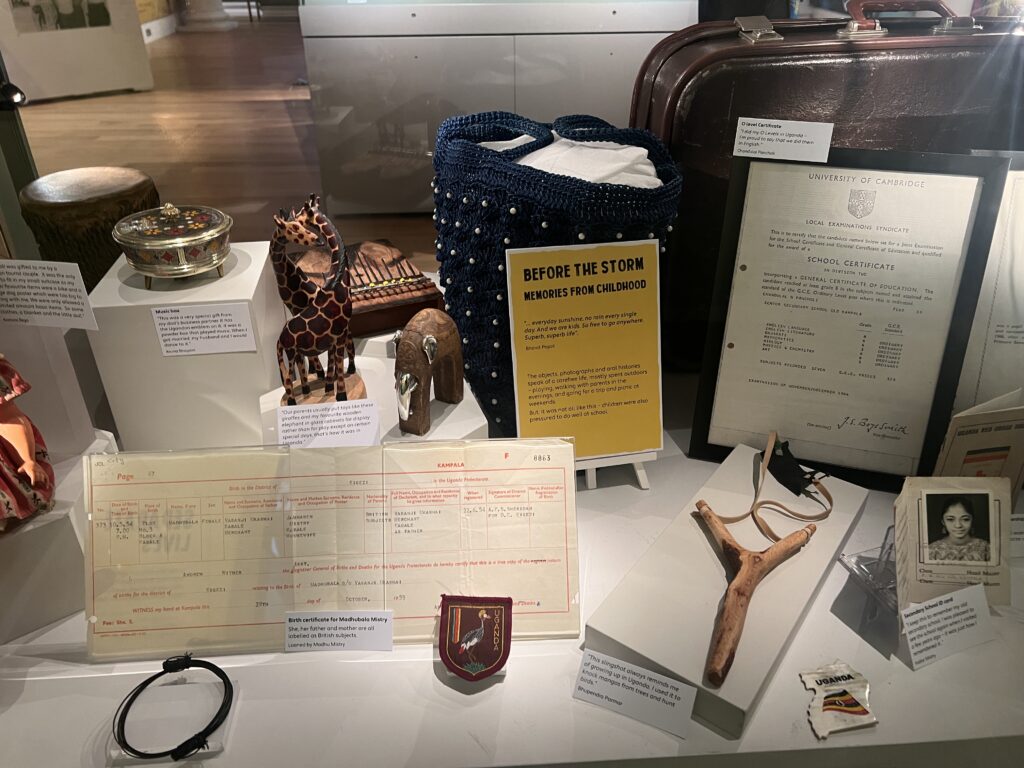

A short walk from The Curve through the heart of the city centre, the Leicester Museum and Art Gallery is hosting Rebuilding Lives, a free exhibition curated by Navrang Arts, a local non-profit organisation.

Visitors can read unfiltered accounts of those who fled Uganda, and reflect on the community’s distinctive influence on Leicester. Ugandan Asians from across the UK contributed items for display as part of the exhibition, including school notebooks and ID cards, slingshots that children used to knock mangoes from trees, transistor radios, record players and vinyls which they managed to get past the Ugandan Army soldiers.

In helping curate the exhibition, Rebuilding Lives’ project director Nisha Popat wanted to honour Ugandan Asians, including her parents. She was eight years old when she was expelled. “I always thought we were going to go back,” she recalls. “I knew there was tension in the house. I knew mum was unpacking. I knew they were upset. But in my mind it was this holiday.”

Over the last six months, alongside gathering information and artefacts, the exhibition team has helped reunite long-lost relatives and friends.

The plays and the exhibition are not only a form of remembering; they’re an indication of how Ugandan Asians have contributed to Leicester’s cultural landscape through food, festivities, and the arts since their arrival here five decades ago. Nisha explains that honouring these stories now allows Ugandan Asians to continue their legacy. “I’m not sure if the story will still be told in 50 years, but I’ve always felt that it’s an important one to tell, keeping these memories alive. We have so much to learn from what happened in 1972, even if it triggers upsetting feelings for us.”

This article was amended on 5 August to remove a line stating that “Amin was allegedly intimidated by Ugandan Asians”.

This article was also amended on 10 August, to change the headline from ‘homeland’ to ‘home’, and to include more context around the history behind the resettlement of Indians to Uganda, and the racial, social, and economic factors surrounding the expulsion.

Following a sensitivity read, this article was amended on 26 October including the recommendations of the sensitivity reader. The changes concerned are largely in the first three paragraphs of the section ‘The expulsion’, detailing further historical context around British colonial rule, and local Ugandan and Ugandan Asian experiences and tensions.

Like what you’re reading? Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Our members get exclusive access to events, discounts from independent brands, newsletters from our editors, quarterly gifts, print magazines, and so much more!