Matt Brown

From London to New York, how many people of colour will die before housing failures are addressed?

Laws meant to keep people safe are going unenforced when it's the most marginalised at risk. What now?

Sabah Hussain

14 Jan 2022

On 9 January, a Sunday morning, a deadly fire ripped through a 19-floor residential building in the Bronx, New York’s poorest borough. The scenes that followed were described by survivors as a “war zone”, stairwells choked by smoke, with 200 firefighters battling through to rescue residents. Seventeen people weren’t so lucky; eight of them children. Many of the dead and displaced were Muslim Gambian migrants. Every single one was a person of colour, the majority Black.

It wasn’t the flames that killed them. It was building code violations, via smoke inhalation. Evidence has emerged the fire started with a space heater and deadly smoke was able to billow through the building thanks to faulty doors that didn’t close automatically – even though a bill passed in 2018 ruled that all New York residential buildings should have self-closing doors.

In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, the new mayor of New York City, Eric Adams, came to a blundering defence of the victims by saying they shouldn’t be attacked for not having closed the door, but that the it was the city’s “obligation to reinforce the concept of ‘Close the Door.'”

As it became clear that residents could not have closed the door, even if they wanted to, Adams’ ‘defence’ looked ever more like stacking blame on the shoulders of the dead, ignoring the negligence that allowed over a dozen people to die.

The Bronx is no stranger to disasters of this kind. In 2007, nine people, including eight children from Mali, perished in a fire caused by another faulty space heater in the basement of a wooden building. Sunday’s tragedy was the second lethal blaze to affect a Bronx apartment building in five years. In 2017, 12 people died in a fire caused by a child playing with a stove. Just days before Sunday’s fire, another 12 people – all Black – were killed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in a three-floor building. Officials said none of the four battery-operated smoke alarms in the building were working at the time of the blaze

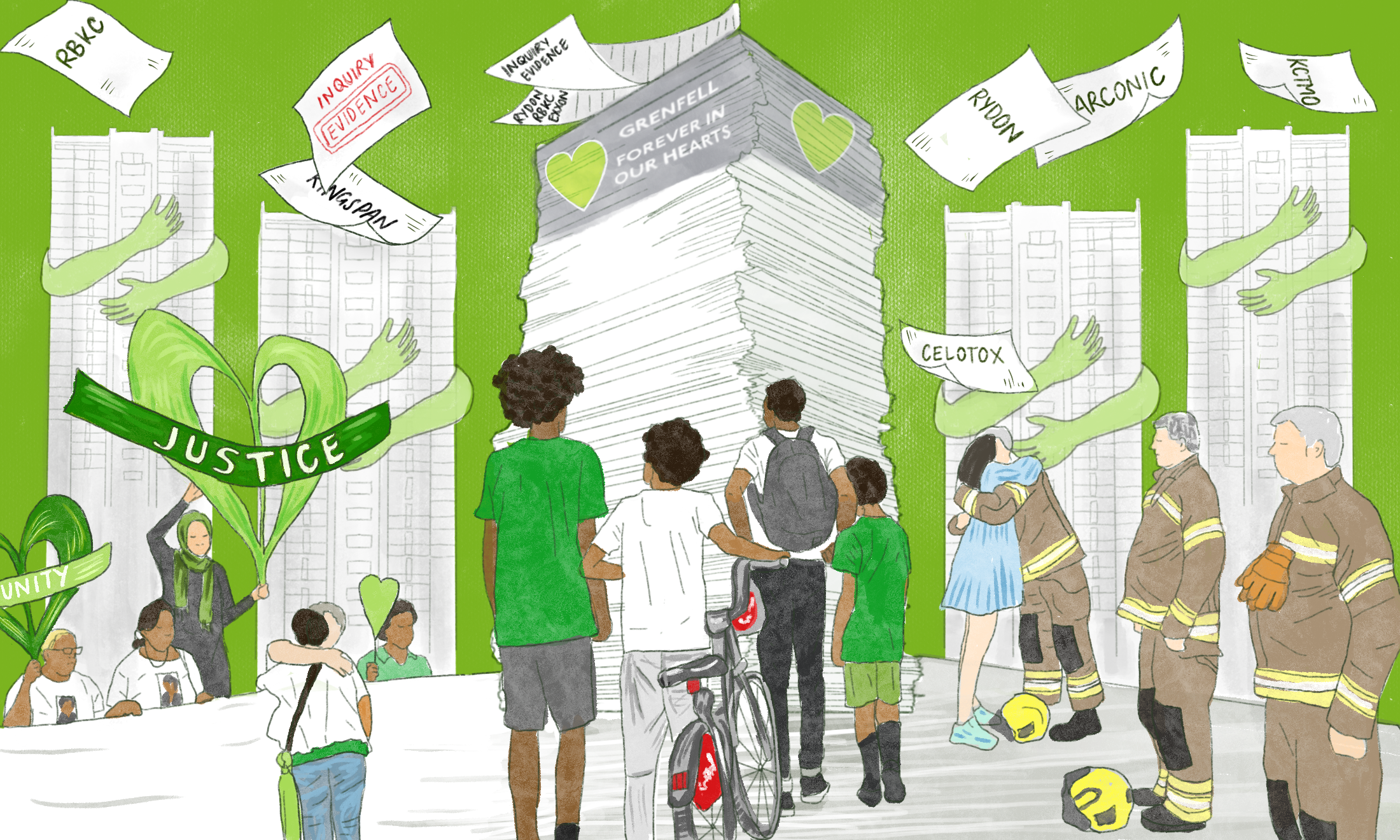

As we near the fifth anniversary of the Grenfell Tower tragedy, these heart-breaking events hit horribly close to home. All-too easily preventable disasters such as this warrant a crude, but necessary, comparison between the working-class communities of colour that have been left to suffer death and loss as a result of a global housing safety crisis.

“We call these “accidents” but we know where these accidents are most likely to happen and they’re most likely to happen to [people of colour] who live in poverty,” journalist Jessie Singer explained in an interview with TIME, in the aftermath of the Bronx fire. Singer’s upcoming book, There Are No Accidents, examines the history of events causing ‘accidental’ deaths, and their disproportionate effects on people of colour.

Class action lawsuits filed against the owners of the Bronx high-rise in recent days claim that the landlords had been previously notified of the “defective conditions” that turned the apartment block into a death trap. An investigation by The Intercept found that two notices of violations were issued to the building in 2021 by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, in relation to “broken or defective fire retardant material” in its walls. The notices meant that the breaches of New York’s maintenance code had been verified by an in-person inspection, and at the time of writing, only one violation was marked ‘closed’.

“It wasn’t the flames that killed them. It was building code violations, via smoke inhalation”

The Intercept also discovered the apartment building had 17 other open violations, relating to vermin problems, mould and lead-based paint. The picture painted is of housing not fit for human habitation – and thus passed off to the most marginalised in society. The direct source of the fire itself is telling; space heaters can often be a “symbol of inequity”, according to Bronx community organiser Julie Colon, often indicative of a lack of proper heating.

Government estimates indicate that portable heaters cause 1,700 fires and claim 80 lives per year in the US. The Bronx, whilst the second smallest in population of New York’s five boroughs, has the highest proportional use of supplemental heating. A number of residents at the Bronx apartment building had previously complained about heating problems, only aggravated by New York’s bitter winter months.

We’ve seen this story before. Damning evidence had indicated that cost-cutting measures could have been scrapped to prevent the 72 deaths at Grenfell Tower, 85% of whom were from ethnic minorities. Tower residents had repeatedly warned the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation, which supervised the high-rise, that there were several fire hazards in the building, in addition to the infamous cladding that ultimately led to the appalling number of casualties.

The parallels between these incidents are too stark to overlook. The authorities that we rely on to keep us safe have repeatedly failed their citizens. If whistleblowing is not the answer, then what is? If laws aren’t enough to protect people, what will? If the glaring pattern of disregard for working-class communities of colour isn’t enough to make people angry, what will? Tenant unions and individual efforts have begun a pushback, but as the “big squeeze” provoked by Covid-19 begins to bite in places like Britain, housing standards are likely to get worse and worse for those unable to afford to protest against poor conditions.

“We can’t wait for another disaster like this to galvanise often short-lived action”

The only effective method seen thus far to provoke change in the UK is individually shaming negligent councils and housing associations – but that relies on the attention span of the public and can’t cover the epidemic of unsafe and ramshackle accommodation people are being forced to live in. So where do we go from here?

The Grenfell Tower Inquiry has been a long, gruelling process, and its end is still nowhere in sight. Each of these tragedies is a shocking and painful reminder that the lives of poorer communities seem expendable in the face of budget cuts and austerity measures. But we can’t wait for another disaster like this to galvanise often short-lived action, and fuel empty promises from political figures, building-management organisations and other guilty parties.

We need to organise ourselves, working with tenant unions and grassroots activists to regularly campaign against the smallest infraction so that those problems don’t grow bigger while we sit on the side lines. There is work to be done and death should not be the only thing that spurs us into action when people’s lives are already at stake.

‘Awaab’s Law’ won’t save Black and brown tenants from malignant social housing

Accusations of exploitation mount against an ‘ethical’ housing enterprise

‘We were all robbed’: Grenfell’s community stands in solidarity on fifth anniversary