Cardiff’s history of migration inspired me to live-tweet the 1919 race riots

Yasmin Begum

05 Nov 2019

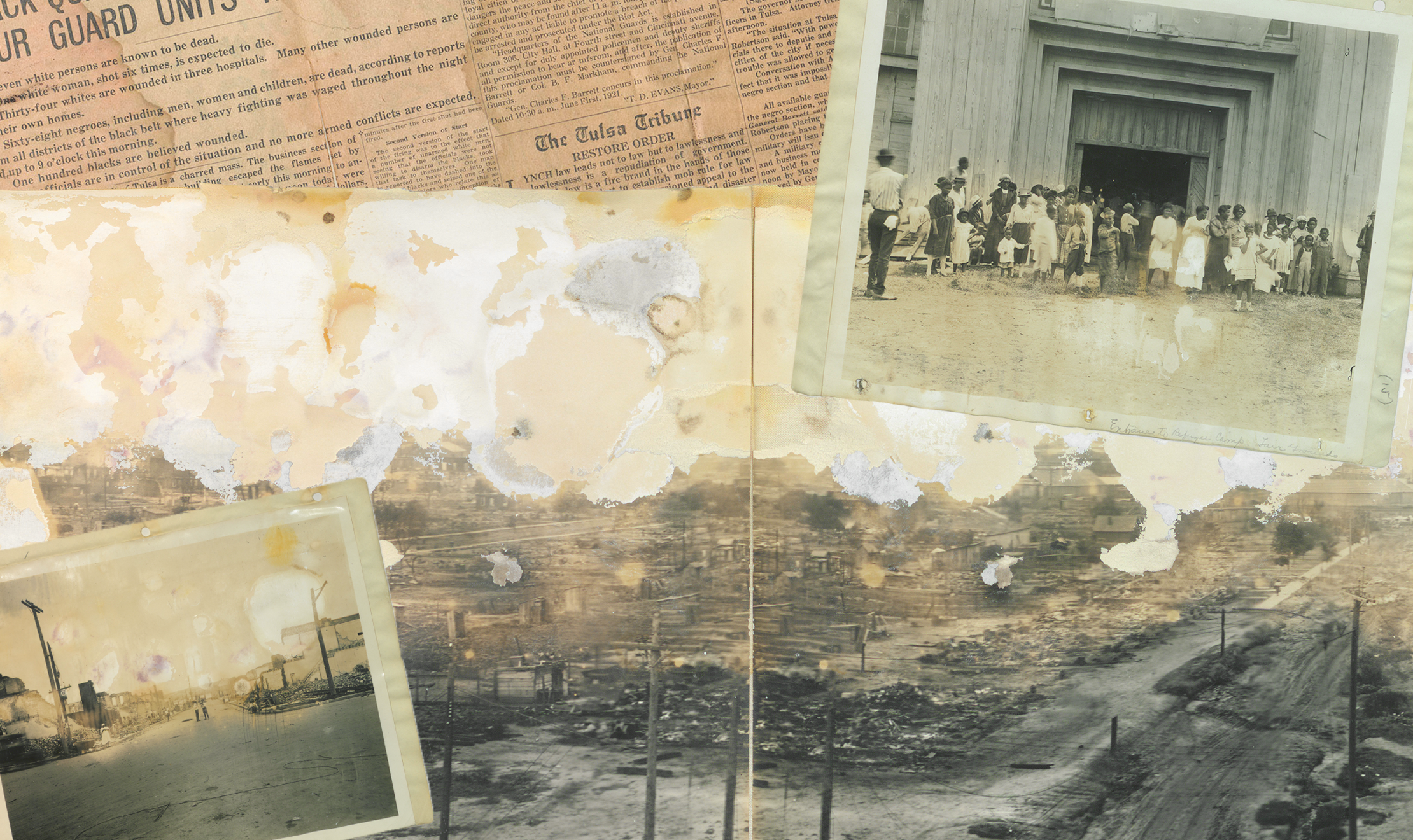

Images courtesy www.tigerbay.org.uk

One hundred years ago in 1919, race riots gripped cities across the UK, including Liverpool, Glasgow and my home city of Cardiff. Not a whole lot is known about the race riots in Wales, despite Cardiff having the second largest population of people of colour outside of London. In fact, as there is currently no full account of the race riots, I decided to live-tweet them.

Most conversations on race are led by and happen between people of colour in Wales. Growing up in Cardiff, there weren’t many (if any) meaningful portrayals of the history and experiences of diverse people in Wales. My friends, seeking to expand the participants of the conversation on race, read more than 30 historical sources to compile lists of what happened on each day during the riots. We scheduled tweets to go out roughly in parallel to how the riots played out. We had a phenomenal response to our tweets, not only from communities in Wales, but from people all around the world.

The riots were the high point of escalating tensions: in the years running up to them, there were smaller racialised and racist altercations across the city of Cardiff. In 1911, Chinese workers had been attacked in Cardiff during a seamen’s strike and further smaller incidents of unrest also boiled over during this period. Widespread unemployment across all working class communities and a perception that men of colour were “stealing” the jobs of former sailors in the post-war period meant that hostility ramped up in the run-up to the race riots of 1919.

Tiger Bay – which became central to the 1919 riots – is an island hemmed in by canals to the north, west and east and the Severn Channel to the south, looking towards England. At the beginning of the 20th century, a revolution in the shipping industry led to the growth of the area. By the early 20th century, Cardiff had the second largest port in the world after New York City and it seemed that labour and coal were set to change the industrial landscape of the world forever.

The population of Tiger Bay was looked down on: seen as a place occupied by wayward white women and “miscegenation”. The Chief Constable in Cardiff, James Wilson, reportedly said: “The coloured seamen who live in our midst observe our laws for the good rule and government of the community. They are not, however, imbued with our moral code and have not assimilated our conventions. They come into contact with the female sex of the white race and heir progeny are half-caste with the vicious hereditary taint of their parents.” After the riots, the PC Constable of Cardiff City suggested a ban on “race mixing” in the city and that men of colour should be stopped from wearing cricket flannel whites because apparently they made them too attractive to white women.

In the Welsh capital, over the course of three days in June 1919, mobs of over 200 people showed up at the properties of people of colour, and people of colour were chased into Tiger Bay from perceived “white” areas. When the white rioters came on the evening of 12 June to Tiger Bay, the police stood at the corner of Custom House Street and Bute Street, warning the rioters that the sailors had guns. Three men died in the 1919 riots, hundreds more were injured and along with thousands of pounds worth of property damage.

Tensions simmered down after the riots. In the wake of the violence, a meeting was organised by men of colour in Cardiff to respond to the events of the past few days. The British state responded by “repatriating”, or deporting, men and brought in the 1920s Alien Order in a bid to quash dissent across the country. Community organisers like Rufus Fenell (originally from Guyana) organised in the Cardiff docks community to stop the deportation of sailors in Cardiff. However, boats continued traversing across oceans to deport people to British colonies, after being subject to three days of intense racial violence perpetrated by white communities. When the men arrived in places like Sierra Leone and Jamaica, they began to agitate against the British Empire in protest of their unjust treatment as British citizens.

Some of the most vicious racist violence in the history of the British Isles occurred during those few days in Cardiff, with horrific consequences. In spite of this, the Cardiff race riots aren’t taught in Welsh schools, and there is currently no museum or historical institution in Cardiff which documents the experiences of people of colour in Wales.

So many conversations on Welsh identity revolve around “Cymru Cymraeg” – Welsh-language speaking Welsh populations – with little room for other groups. Equally, conversations on race in Britain are mainly focused on communities in England. We live-tweeted the race riots to try and bring attention to this piece of hidden history; by raising ourselves from the footnotes, we can start to reclaim our narratives.

If you would like to stay in touch with the 1919 Race Riots collective, you can follow them @1919RaceRiots or email: Cardiff1919raceriots@gmail.com.