Remembering the L8 Uprising: 40 years on from the Toxteth ‘Riots’, has life changed for Liverpool’s Black residents?

Tensions between people and police remain from riots in the heart of Liverpool’s Black community four decades ago.

Nali Simukulwa

30 Jul 2021

BBC Panorama

Anyone searching for Black culture in Liverpool, from Afro hair care products to Caribbean food, can expect to be directed to Lodge Lane, Toxteth, L8. The area has always been the epicentre of Blackness in the city. And this July marks 40 years since the inner-city neighbourhood went up in flames.

For many in England, referencing unrest in 1981 summons memories of burning cars in Brixton. But in the north, racial tensions were also rising as Black communities grew tired of police mistreatment. In Toxteth – home of the oldest continuous Black population in Europe – police stopped and questioned a Black motorcyclist on Selborne Street, a common practice under ‘sus’ laws that existed at the time which allowed officers to question anyone they suspected of “loitering with intent to commit an arrestable offence”. Nearby community members saw this treatment as unfair and began protesting, culminating in Leroy Cooper, a young Black friend of the motorcyclist, being arrested and carted away in a police van that onlookers pelted with stones.

The clash was a spark that finally saw the tinderbox that was Toxteth burst into flames. Since Black people began settling in Toxteth the early 1900s, the community had faced immiseration due to spending cuts, police discrimination and poor housing. Unemployment rates among men in Riverside (the constituency encompassing Toxteth) had reached 41% in 1981, the highest in Great Britain.

“One citizen, David Moore, died after being hit by a police Land Rover during a disturbance, while more than 700 police officers were injured, 500 people were arrested and damage to property reached £11m”

Residents at the time remember feeling confined – crossing the border into the neighbouring areas as a Black person carried the risk of assault or harassment. The events of 3 July sparked nine days of rioting, finally ceasing on 28 July. One citizen, David Moore, died after being hit by a police Land Rover during a disturbance, while more than 700 police officers were injured, 500 people were arrested and damage to property reached £11m. It was the first time CS gas, an aerosol spray used by UK police forces as a temporary incapacitant, was used outside of Northern Ireland.

Memories of the riots remain vivid in those present at the time. Some residents now tell gal-dem they prefer the term ‘uprising’ to better represent the political and social context of the events of July 1981. Yet, as time passes and Toxteth becomes gentrified, these protests – dubbed “the most serious rioting in mainland Britain” – risk being forgotten by younger generations. Distrust in the police is often cited as the uprising’s most significant causal factor. This attitude is a looming consequence of the events, as doubt in the police continues to simmer among young Black people currently living in the area. Forty years on, gal-dem asks, how much has life changed for Black residents in L8?

A divided city

Residents describe L8 as a community where neighbours could rely on one another for help and social hubs such as the Ibo Community Centre allowed residents to come together often. “It was a community where we always did things together, I don’t think there’s anywhere like it in the city, it will always be my home,” says Helen*, a Black woman of mixed British and Nigerian heritage who lived in Toxteth from her birth in 1969 until 1994. Community spirit was entrenched into daily lives of residents as local families formed friendships that spanned generations.

Helen remembers the parties in particular. Discos at the Methodist Centre on Princes Avenue, dances at the Caribbean Centre on Upper Parliament Street, and the annual Toxteth Carnival each summer. “Now, when I’m out with my kids and I greet people, they say to me ‘God, you know everyone,’ but that’s what it was like,” she says.

“The police relentlessly targeted the Black community. It’s different now, the mindset is still there but the legislation has changed which makes it harder for officers to be as overtly racist”

Chantelle Lunt

Yet Toxteth’s tight-knit, Black community was also subject to widespread mistreatment from white residents and police. In the 1980s, a police officer “could put you in a car, say you fit a description and charge you without evidence,” says Chantelle Lunt, who founded Liverpool-based anti-racism group Merseyside BLM Alliance in 2020. “The police relentlessly targeted the Black community. It’s different now, the mindset is still there but the legislation has changed which makes it harder for officers to be as overtly racist,” she adds.

Young people from Toxteth today echo this view. Their stories about racism in their area are often tales passed down generations. “Overt racism was more prevalent when I was younger or in stories that my mum tells me,” says Lehtu Mpetha, a 17-year-old Toxteth resident. “My uncle was racially attacked in a nightclub in the early 2000s before I was born.”

At 11, Helen says she was too young at the time to fully understand the cause of the riots. Yet she remembers the identity struggle the riots evoked for her. “During the riots, I knew that I wanted to be a police officer but I thought, ‘well, I can’t do that anymore.’ I put that ambition to bed until years later.” Helen was put off, fearing that being from Toxteth would hinder her career in the police. But her belief that change in organisations must come within pushed her to apply for a position on the force.

Despite witnessing police behaviour both in the lead up to the uprisings and during them, Helen was accepted into Merseyside Police as an officer in 1994 and became a serving ‘bobby’. Her decision didn’t make her popular within the Toxteth community, where police racism still loomed large. “I got negativity from the community when I started,” she remembers, including comments and judgement from people around her.

Now, though, Helen believes there has been progress – to a degree. “Over the 27 years I’ve served, people have recognised that I stuck it out and that I didn’t sell my soul to the devil. I came in to make a difference and I’d like to think that I’ve done that,” she says.

However, she admits that while police relations with the Black community are better compared to the 1980s, too little has changed, particularly regarding officers’ conduct during stop and searches. Others disagree. Leslie, a 20-year-old from Toxteth, agrees, tellings gal-dem that as a Black person, she feels “the police system needs rebuilding,” before she would ever consider joining the force.

Community spirit did not wane following the riots. The aftermath saw the creation of grassroots activist groups as galvanised residents sprang into action. Liverpool Black Sisters and the Steve Biko Housing Association are just some of the organisations founded out of the rubble of the riots in L8. Toxteth was never restored to quite how it was before the events of 1981, as many of the buildings destroyed in the events were never rebuilt. Yet community collectivism became a lasting legacy.

Policing in the present

Despite community efforts, racial tensions too have persisted for the last four decades. “There is definitely hostility towards the police, there is still anger because of what they’ve done in the past,” says Lehtu. Current Toxteth residents report a persistent and disproportionate police presence in their area, and in May 2021, the area saw 119 stop and searches carried out amidst expanded pandemic policing, compared to just 15 such incidents in the more affluent, neighboring area of Aigburth.

“The police send many of their Black officers to Admiral Street in the heart of L8 so that they look less racist and [so that] people are treated by officers who look like them, which is strategic,” says Merseyside BLM alliance founder Chantelle Lunt, of the way Merseyside Police interact with the Toxteth community now. (gal-dem contacted Merseyside Police for comment, but did not receive a response to queries by the time of publication).

Lunt herself served as a Merseyside police officer from January 2017 before leaving in August 2018 after experiencing sexism and racism within the force, leaving her feeling disillusioned. While she felt the community’s reception to her own presence as a police officer was positive, she attributes this largely to her being Black. She also noticed the disparate service delivered by her colleagues. “My white colleagues interacted differently with Black people. They’d be more firm, they would have a certain tone. They would constantly try to manage Black people, whether they were victims or suspects.”

“Black people have infamously fallen foul of stop and search procedures since the formation of the modern police force”

Chantelle describes a training package introduced into the force around the time of her departure in August 2018, where she and a Black colleague were asked to role-play suspects so other officers could practice stop and searches. “The force wanted to encourage its officers to search diverse communities and didn’t want officers to avoid searching people just because they’re Black,” she says. Government statistics show that this has never been an issue the police have struggled with before; Black people have infamously fallen foul of stop and search procedures since the formation of the modern police force.

The pattern continues today; figures from 2019/2020 show that Black people in Merseyside are three times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people. In a statement marking the 40th anniversary of the Toxteth riots, Chief Constable of Merseyside Police Serena Kennedy said that the force is trying to improve the fairness of stop and search through measures like the wearing of body cameras by officers, and that the practice was a “crucial power” in tackling criminality. Research suggests otherwise.

Chantelle cites policing tactics like stop and searches as the reason for continued distrust in the police in L8. “If they wanted to keep communities safe, they’d do more local policing and build bonds that way but they’re not, they’re increasing heavy handed tactics and bringing in police who don’t know the area. The policing strategy is completely flawed.”

“From the 1980s to now, there should have been a lot of change but that’s not the case,” says Shaneia, 19, referring to the case of 18-year-old Mzee Mohammed-Dailey, who died after he was restrained by police officers at the Liverpool One shopping centre in 2016. “Things like that really strain the relationship between the police and the community,” says Shaneia, who lived in Toxteth from 2007 to 2017.

A changing neighbourhood

Before the riots, members of the Conservative party under Margaret Thatcher had suggested that poorer areas of Liverpool be left to fall into “managed decline,” and following July 1981, Thatcher’s government committed few funds to the recovery of L8. Some local Black-owned businesses in the area never reopened as they were damaged beyond repair. While some businesses continue to thrive in areas like Lodge Lane, nowadays, many of the once populated streets of Toxteth are lined with vacant houses, while Liverpool’s Black residents have dispersed throughout the city.

Gentrification too is a looming threat. In 2017, the ‘Baltic Triangle’ – a collection of bars and restaurants that border L8 and Liverpool city centre – was named one of the “hippest areas of the UK,” despite the fact that its creation drove local communities out of the area. New migrants from countries such as Yemen, Iraq and Somalia have allowed Toxteth to maintain its diversity, but as property developers seeking investment opportunities take interest in the area, original communities risk being priced out. “That area was full of housing associations and now they’ve started gentrifying it. In my day, it was a red light district and now it’s now called ‘The Georgian Quarter’ and I’m like, ‘really?’” Helen says.

“40 years on from the riots, Toxteth faces many of the same issues. But the legacy of these events has encouraged residents to use the resources they have to fight for change”

Young people have also noticed this change, “I have lived in L8 my whole life and I think this area is being gentrified,” says Lehtu. “More students are moving in but I don’t think the spirit of the community can be watered down, there’s too much history.” As Black residents disperse out of Toxteth, Liverpool’s Black community face new issues in the fight against racism. With more Black people relocating to less central areas of the city where the demographic is predominantly white, their risk of facing overt racism increases, says Chantelle.

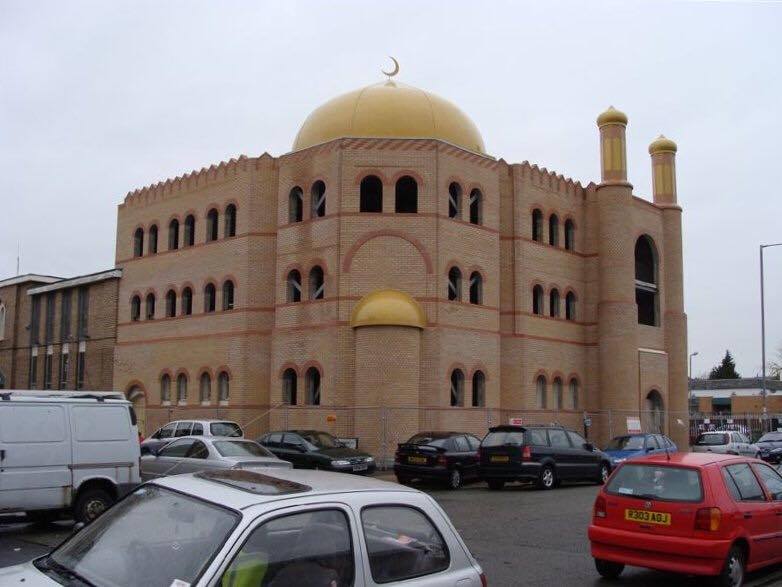

In these instances, groups like Merseyside BLM Alliance are plugging the gap, Chantelle explains. “You might be alone in those areas but we have this online group where you always have a community.” Recently, Merseyside BLM Alliance helped to fundraise more than £650 for a victim of a racist hate crime. Local residents also stepped up to help each other during the pandemic with members of the Al-Rahma Masjid Mosque delivering care packages and essential items to those in the L8 area who found themselves in need.

After the riots, Toxteth residents collaborated to push for change and in 2021, groups like Merseyside BLM Alliance show the community’s enduring ability to build support networks. Liverpool now also has more Black representation in city politics than ever before. Kim Johnson, Labour MP for Riverside, represents Liverpool in Westminster, and in May this year, Liverpool became the first major UK city to be led by a Black woman as mayor with Joanne Anderson assuming the role. The city also concurrently had a Black Lord Mayor in Anna Rothery. “When I was younger, you didn’t see people who looked like us in power,” says Chantelle.

Toxteth is a community determined not to be beaten down. 40 years on from the riots, Toxteth faces many of the same issues. But the legacy of these events has encouraged residents to use the resources they have to fight for change, whether that be trying to enact change from within as uniformed officers or on the ground as activists. Younger generations continue to take to the streets to protest for their rights and as the face of Toxteth changes amid gentrification, members of the community display solidarity for the causes affecting their neighbours.

The pandemic and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 meant residents adapted further; the internet replacing the shared community spaces of days past. Four decades on from the riots that destroyed much of the physical neighbourhood in Toxteth, the community’s resilience has meant residents unfalteringly support each other through difficulty, even when the institutions meant to protect them do not.

*Name has been changed to protect identity.

In a statement provided by Merseyside Police to gal-dem post-publication on 30 July 2021, Assistant Chief Constable Matthew Boyle said: “We do not and we have never selected officers to work in a particular area of the Force on the basis of their ethnicity,” regarding policing in L8. Regarding the training package referred to by Chantelle Lunt, Boyle said that Merseyside Police “do not focus search powers on specific members of our communities”.