Photography courtesy of Shanice Bryce & Island Social Club, Design by Karis Pierre

Is Black British Food culture finally getting the recognition it deserves?

Shanice Bryce

22 Oct 2020

Celebrating Black History Month with support from Sainsbury’s

Britain has long had an unquenchable craving for food from other countries. Over the years, the increase in access to food from the African diaspora has found its way from kitchen cupboards, to the sidelines of street markets and onto British supermarket shelves. This shift in the culinary landscape is testimony to the rich history of immigration and the myriad of cultures in Britain.

Although you’ll find some of the nation’s favourites in Black kitchens; like Sunday Roasts, food cultures from the African diaspora have had a hard time gaining the culinary accolades received by their non-native counterparts. In a 2018 article, writer Riaz Phillips asked, “If tikka masala, teriyaki, and dim sum can make their way into Britain’s culinary lexicon, then why not kenkey, fufu, suya, and chin chin?” Or spicy doubles, tangy injera, creamy rundown and sweet, baked gizzada.

Much of our cooking has been about maintaining connections with our heritage, fostering community, and getting people acquainted so that the tastes and names of dishes roll effortlessly off the tongue.

The Afro-Caribbean culinary trajectory is an apparent thread from West Africa, resulting from the transatlantic slave trade, where many West African’s were taken to the Caribbean. Post-war communities – particularly the 50s Windrush generation and the migration of West Africans in the 80s – brought with them saltfish, savoury breadfruit, bitter callaloo, soft yams, sweet plantains, hearty soups, and stews.

They cooked dishes from back home amid their efforts to integrate in Britain and create a sense of home. With that, a confluence of food cultures emerged. Independent grocers and stalls carved out space at street markets such as South London’s Electric Avenue Brixton – also known as “Little Jamaica” – and East London’s Ridley Road, where one could find some of these ingredients.

Today, many of us can find our heritage food staples in the “world food” sections of British supermarkets, unlike our precursor communities, where they were not so accessible. Now we see green plantain, starchy cassava, and fresh chayote opposite the apples and oranges. It’s enabled people who don’t shop at local markets or have access to them, to be exposed to the traditional ingredients of those who have been essential in shaping British culture.

Mitu Chowdhury, organising secretary of the Bangladesh Caterers Association believes, “when food can be bought cheaply as takeaways, it is not taken as seriously as typically more expensive European cuisine”, thus sometimes being seen as not “sophisticated” enough. Take the precious technicalities of flaky Jamaican patty pastry or Nigerian Pounded Yam, and how we’ve weaved the nuances into the very fabric of British culture, that in itself is a sophisticated doing.

Currently, many long-standing eateries are battling to survive austerity and the impacts of gentrification. In Tooting market, The Lone Fisherman faced near eviction, drawing similarities to the 1992 closure of the legendary Mangrove restaurant in West London’s Notting Hill. But more restaurants that span African and Afro-Caribbean cuisine are opening their doors across Britain. They investigate our heritage through food, rooted in community, and inspired by the British ingredients readily available to us. This exploration of our respective cultures has inspired culinary innovation. Take eateries like Chuku’s, a sibling-run Nigerian tapas restaurant, or 12:51, a British Caribbean restaurant by chef James Cochran, and the likes of Island Social Club, active in exploring their British Caribbean culture and identity.

“The popularity and the creativity of Afro-Caribbean and African food spaces have only been given its time in the last five years”, says Marie Mitchell co-founder and chef at Island Social Club. “I think what’s exciting is that we’ve found ways of crafting our versions, specifically influenced by the massive amounts of cultures and cuisines in London and applying that to our heritage. It’s a way to invite others that don’t know about the cuisine in the same capacity.”

Perhaps, the growing popularity of food from the African diaspora, among British people, has been inspired by increasing interest in Black British culture, particularly in visual arts, writing and music. I’m sure we can all agree that Britain has benefitted from the enrichment of non-native food, so it’s only right that we honour, support, and, most importantly, protect them.

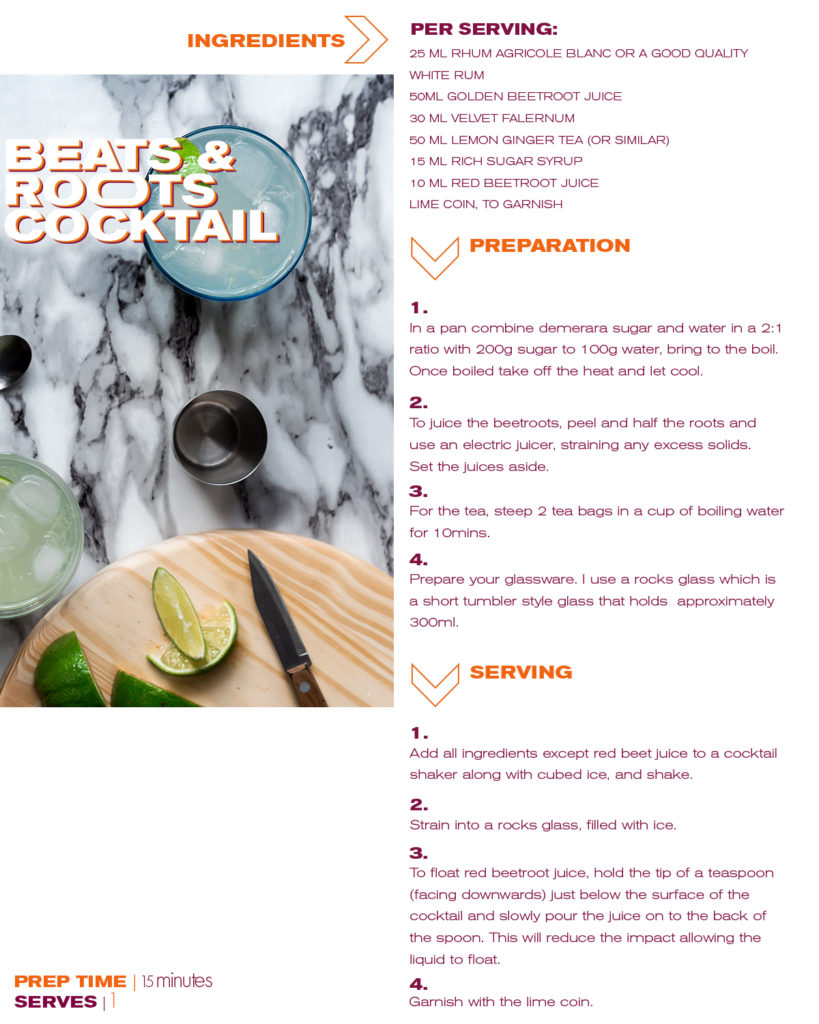

To rep Black British roots Joseph Pilgrim, co-founder of Island Social Club, has put together a “likkl” drink that takes an earthy root vegetable still available in the British autumn, and turns it into something exciting and fresh.