Photography courtesy of Safiya Robinson, Design by Karis Pierre

This Black History Month we’re asking, what puts the ‘Soul’ in Soul Food?

Safiya Robinson

22 Oct 2020

Celebrating Black History Month with support from Sainsbury’s

Although traced back as far as the 1800s (the first known African American cookbook is dated 1881), soul food has been a core part of the Black American collective identity since the 1960s, amidst the Black Power Movement and the Black Arts Movement that ushered in a renaissance of Black creativity, community, resistance and radical Black imagination. Soul Food was famously championed by poet and playwright Amiri Baraka, who incidentally officiated my grandparents’ wedding. My mama is from Harlem, and my childhood memories of New York consist of sweet potato, pecan and butterbean pies, chicken and biscuits, Popeyes popcorn shrimp and lots and lots of pancakes.

London is painfully lacking in authentic soul food restaurants, but the cuisine continues to live in my mind rent-free. I’m listening to a playlist (joints and jollof, inspired by all things food) as I write this. Big K.R.I.T sets the tempo as Raphael Saadiq croons in his signature tone, “damn I really miss those times, that soul food’s on my mind”.

I am instantly transported to my grandmother’s house, watching her prepare collard greens at the stove. To my aunt’s house, as my cousins and I dance around the kitchen to soul classics while she whips up her mac n cheese (check out my infamous vegan version here). To the family-owned BBQ spot on the side of the highway, somewhere in California, where I tried my first hushpuppy (deep-fried cornbread dumplings, typically eaten with greasy fried catfish and a big ol’ pile of greens). The playlist changes, and Nas and Busta Rhymes remind me that fried chicken is indeed a fly vixen.

When I was first contemplating veganism I was in North Carolina visiting my godmother, a chef, who looked at me incredulously and refused to let me order the vegetarian option (in 2014, vegan options were few and far between). Now the flavour profile of authentic southern fried chicken lives within me, and my cauliflower wings bring all the boys to the yard.

A permanent fixture at most family events – from Christmas to christenings – soul food evokes feelings of pleasure, joy, nostalgia and familiarity. I remember when I worked in the kitchen at somebody else’s family reunion in Ohio, and some slight confusion led to my name being called out on the mic, shouting out the “cousin from England” who had everyone eating good. “We all family, especially when it comes to bbq”, and definitely when it comes to soul food.

But with many soul food dishes derived within the context of the transatlantic slave trade, soul food has a marketing problem.The belief by many that soul food is unhealthy, uninspiring and low quality is an egregious misrepresentation of the plethora, range and possibility of the cuisine.

As is our way, we did the best we could with the little we had. It resulted in incredible creativity, boundary-pushing flavour combinations and dishes reflecting the intricacies and subtleties that make up the Black experience. We were the original sustainability champions, making magic out of scraps, and the continuation of West African cooking and agricultural practices was in steadfast resistance to the conditions of our enslavement. (Check out Soul Fire Farm, a BIPOC led farm in New York, and Land In Our Names, a grassroots British collective, who are continuing this legacy!).

What I love about soul food is its clear links to the African continent and to the wider diaspora. In Jamaica, we have saltfish and festival, Zimbabwe sadza and greens, across West Africa fufu, moin moin, red red and efo riro. Multiple variations, all influenced by their unique contexts but still beautifully connected. We have been cooking the way we always have, with the same ingredients that nourished our ancestors, despite our forcibly (through slavery and colonialism) scattered locations.

Beyond this, soul food is about more than just the individual ingredients used. The queen Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor says it best, “Soul food depends on what you put in it. I don’t mean spices either. If you have a serious, loving, creative, energetic attitude towards life, when you cook, you cook with the same attitude. Food changes into blood, blood into cells, cells change into energy which changes up into life and since your lifestyle is imaginative, creative, loving, energetic, serious, food is life. You dig.”

Viewing soul food as unhealthy, outdated and limiting is unimaginative, pessimistic and ultimately anti-Black. The foundations of soul food are beans, cornmeal, greens and pork. Hold the pork and we’re left with some highly nutritious ingredients that can both be left simple and highly elevated, for family reunions to Sunday dinners to fine dining. Erykah Badu did say that vegan food is soul food in its truest form.

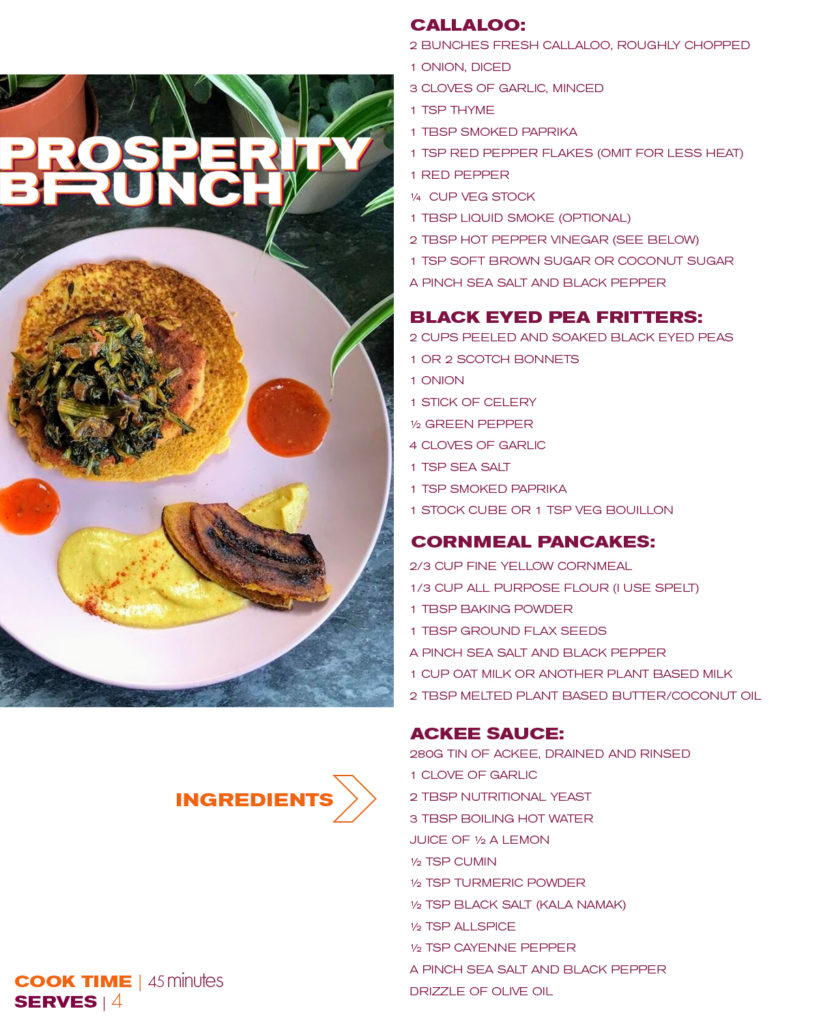

Every year on New Year’s Day we make black-eyed peas, collard greens and cornbread to usher in prosperity. Black-eyed peas to represent coins, collard greens for money and cornbread for gold. 2020 has been a lot, so I thought we might need to usher in some prosperity a few months early. For a traditional recipe, look no further than Mashama Bailey, who is doing incredible things with soul food and Southern cooking. Her Chef’s Table episode is a must-watch.

I was going to give a basic recipe for these dishes, but I wanted it to reflect my Black experience, as an African American born and raised abroad in London’s melting pot. What does soul food mean to me? This dish is a love letter to the Black diaspora, my heritage on a plate! I’m a millennial, so I had to create a brunch dish right? Savoury cornmeal pancakes, fresh callaloo instead of collards, a nod to my Jamaican grandfather, and a black-eyed pea fritter inspired by Nigerian akara. It’s all tied together with a creamy ackee sauce and hot pepper vinegar. Now that’s some good eatin’, good seasonin’!