Unsplash/Juan Manuel Nuñez Mendez

Chileans have rejected radical constitutional change. But the people will see this movement through

More than 60% of voters rejected Chile’s new, progressive constitution in a major blow for the left. But this process came directly out of the people’s protest, and their strength should be remembered.

Naomi Larsson Piñeda

06 Sep 2022

In the days running up to Chile’s historic vote on a new constitution last week, thousands took to the streets in Santiago to support the Apruebo (approve) campaign in a movement that echoed the social uprising three years ago. I still remember the feeling of the days spent in the streets during those anti-inequality protests; the banging pots and pans acting as the soundtrack for a collective feeling of hope and change. After seeing the hundreds of thousands of people marching the streets of Santiago in favour of the world’s most progressive constitution, I felt that same hope.

But like so many Chileans, I woke up a day after the results dismayed; painfully disappointed that the majority could reject the principles of equality and respect outlined in the new charter. Principles that came out of a direct cry from demonstrations that shook the nation in 2019.

It was almost three years ago, on 18 October, that people in this conservative and complex country – yet a country that feels so close to my heart – told the world they had had enough. They’d had enough of neoliberalism’s hold on their lives, of the rising cost of living, of their social services trapped by privatisation, of social and economic inequality.

The months-long uprising, known as the estallido social (social explosion), was sparked by an increase in rush-hour metro fares in the capital. The then rightwing president Sebastian Piñera had told people to get up earlier to avoid paying those increased fees – an unhelpful response that feels echoed by British leaders in the face of the cost of living crisis. Instead of policy change and assistance, the UK government is telling the public to get new kettles and put reflective foil behind our radiators as energy prices rise to the extreme. In Chile, school students took a stand against the rising fees and collectively jumped the barriers in a powerful symbol of defiance. This brave act of resistance is something we should all learn from in the UK.

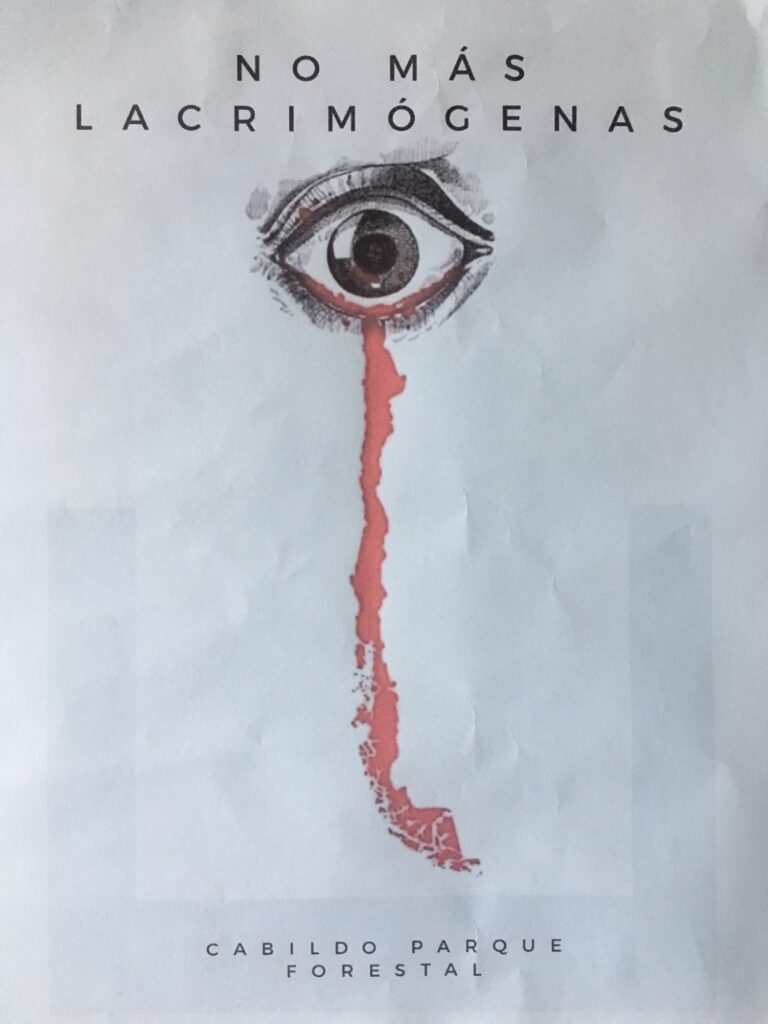

This action soon metamorphosed into a nationwide movement calling for change that saw demonstrations take place daily until December. There were riots – infrastructure was destroyed and shops looted – but the violence overwhelmingly came from the state in trying to suppress the protests. Security forces committed a wave of human rights abuses as tens of people died and thousands were injured in those months. The image of an eye with a blood-red tear falling in the shape of the country became a symbol of the protests, as more than 445 people suffered ocular traumas as a result of crowd control weapons, and two people were blinded completely. These abuses were a violent reminder of Chile’s dictatorship 30 years prior that suppressed any form of dissent.

Amid the calls for change, many Chileans demanded a rewrite of the 1980 constitution borne out of Augusto Pinochet’s military rule, and after a month of unrest, the government eventually agreed. Since the estallido, the country has appeared to be on a route to progress: the leftist millennial Gabriel Boric and former student protest leader was elected president in December 2021. And after almost 80% of the population agreed to replace the dictatorship-era constitution in 2020, in May 2021 Chileans largely voted for leftist and independent candidates to be the ones writing the new draft in a people’s assembly. The proposal that emerged from this process was the world’s most progressive.

But when this draft was put to a referendum on Sunday, over 60% of Chileans voted to reject it. In the run-up, polls had predicted the reject camp would pull through, but no one thought there would be a 24-point margin.

“For an overwhelming majority to reject these ideas suggests the world is not ready for equality”

It is a tremendous blow for the left and for progress. The constitution was a charter of hope and equality. It guaranteed gender parity across the state and its institutions – not seen anywhere else in the world. It enshrined Indigenous rights for the first time in the country’s history, and it protected environmental rights.

In this document, everyone had the right to equality and any form of discrimination was prohibited. “In Chile, there is no privileged person or group,” it wrote. It ensured that everyone had the right to education, including sexual education and environmental education. In a country that is naturally diverse, experiencing historic drought, glacier loss and its resources ravaged by mining and agricultural industries, the constitution protected nature, water and glaciers.

The proposal would have seen vital progress for the country’s Indigenous populations too. With their presence guaranteed at governmental and regional levels, and prohibiting forced assimilation and destruction of their cultures, their rights would have been protected. In attempting to acknowledge traumas of the dictatorship, which saw tens of thousands of people forcibly disappeared, it wrote that the state must prevent and investigate human rights violations, and no person shall be subject to enforced disappearance.

For an overwhelming majority to reject these ideas suggests the world is not ready for equality. In Chile, certainly, many people are not ready for substantive change.

The results have exposed that the shackles of its rightwing past remain firm. Chile was a guinea pig for neoliberalism dreamed up by the Chicago Boys in the 1970s – a set of market-oriented economics and form of capitalism that the UK and US have also taken on, and a model that has contributed to widespread environmental destruction in the pursuit of profit. The current constitution enshrined these neoliberal policies like privatisation, and will remain until a new draft is agreed. Chile’s largely rightwing press has much to answer for, engaging on a campaign of fake news and lies that the new constitution banned private ownership or that a ‘flood’ of new migrants were allowed to vote in the plebiscite.

But it would be too simplistic to say this is a victory for the right. It is a huge loss for the left for sure, but the constitutional referendum goes beyond these divisions. With 388 articles, the 170-page charter was felt to be too long and inaccessible for many people. The suggested shake-up of the political system – like renaming the senate and restructures to the judiciary – was seen as too experimental and unnecessary for some. It also tapped into fundamental and deep injustices and racism within the country – many believed there were ‘too many rights’ given to Indigenous peoples.

I look at the results of Sunday’s referendum and see a very different country from the one that birthed the 2019 movement. The years since have been dominated by a pandemic and an economic crisis that’s put Boric’s government under severe strain, with inflation reaching 13%. His government and the country now face even more uncertainty; Boric plans to repeat the constitutional process, but the reform process itself is up for debate. “We have to listen to the voice of the people. Not just today, but the last intense years we’ve lived through,” the president said after the results. “That anger is latent, and we can’t ignore it.”

But there is still so much to hold onto. The work of the constitutional convention, despite its failings, and all the activists who campaigned for Approve should be celebrated. That the constitutional convention was made up of gender parity, with Indigenous people having a seat at the table, and that those rights were enshrined throughout the proposal, should be seen as an example to leaders across the world. I was moved by the articles that condemned human rights violations as I know so many still live with the trauma of the dictatorship that’s been inherited through generations. I witnessed and reported first-hand the extreme violence of the police and military three years ago, so acknowledging reform and justice for survivors is essential.

But it feels most important of all that we remember where this move to rewrite the country’s charter began. The government’s decision to put the constitution up for vote in the first place was a direct response to the people’s protest. This experiment in democracy came from the people; from the children who shouted for free and equal education, to the elderly who called for better pensions and free healthcare, to the people who lost their eyes in the fight against inequality. They all got us to a place where people across the world are discussing and questioning what the principles of a country should be founded on – and that is an incredible feat.

It didn’t make it through this time, but Chileans will continue fighting for a better future.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Our members get exclusive access to events, discounts from independent brands, newsletters from our editors, quarterly gifts, print magazines, and so much more!

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?