Nadine Nour el Din

Compulsory heteronormativity in my South Asian community convinced me I was straight for 18 years

How do you navigate a world that only tells you to exist as a straight person?

Haniya Bukhari and Editors

19 Feb 2021

I’ve always found resentment to be a funny thing, it bubbles away slowly for what feels like years, sometimes maybe it has. It cooks away like a saucepan full of rice in boiling water, the steam escaping from the lid and the frothing water tickling the lid of the pan with increasing anger. You keep an eye on it, fully aware it’s about to tide over if you don’t lower the heat, but you find yourself momentarily distracted. Then, just like that, the bubbling water has crawled over the silver walls of the pan, sizzled all over the stove and in the process of cleaning up the mess, you’ve scorched your fingertips without even realising.

You might be wondering why I’ve decided to discuss my ineptness in the kitchen, but this is the analogy my brain automatically conjures when thinking of my building resentment over the years towards both my stifled queerness growing up in a Pakistani household and the heteronormativity I was consistently exposed to.

Heteronormativity can be defined as ‘noting or relating to behaviour or attitudes consistent with traditional male or female gender roles and the assumption of heterosexuality as the norm’. Regardless of my pride towards the vibrance, food and diversity that encompasses so much of what I love about my culture, the patriarchal roots and misogyny are profound. Expected gendered behaviours were ingrained into my frontal lobe from as young as I can remember, and it didn’t take long for me to begin to question the uncomfortable disparities.

“Expected gendered behaviours were ingrained into my frontal lobe from as young as I can remember”

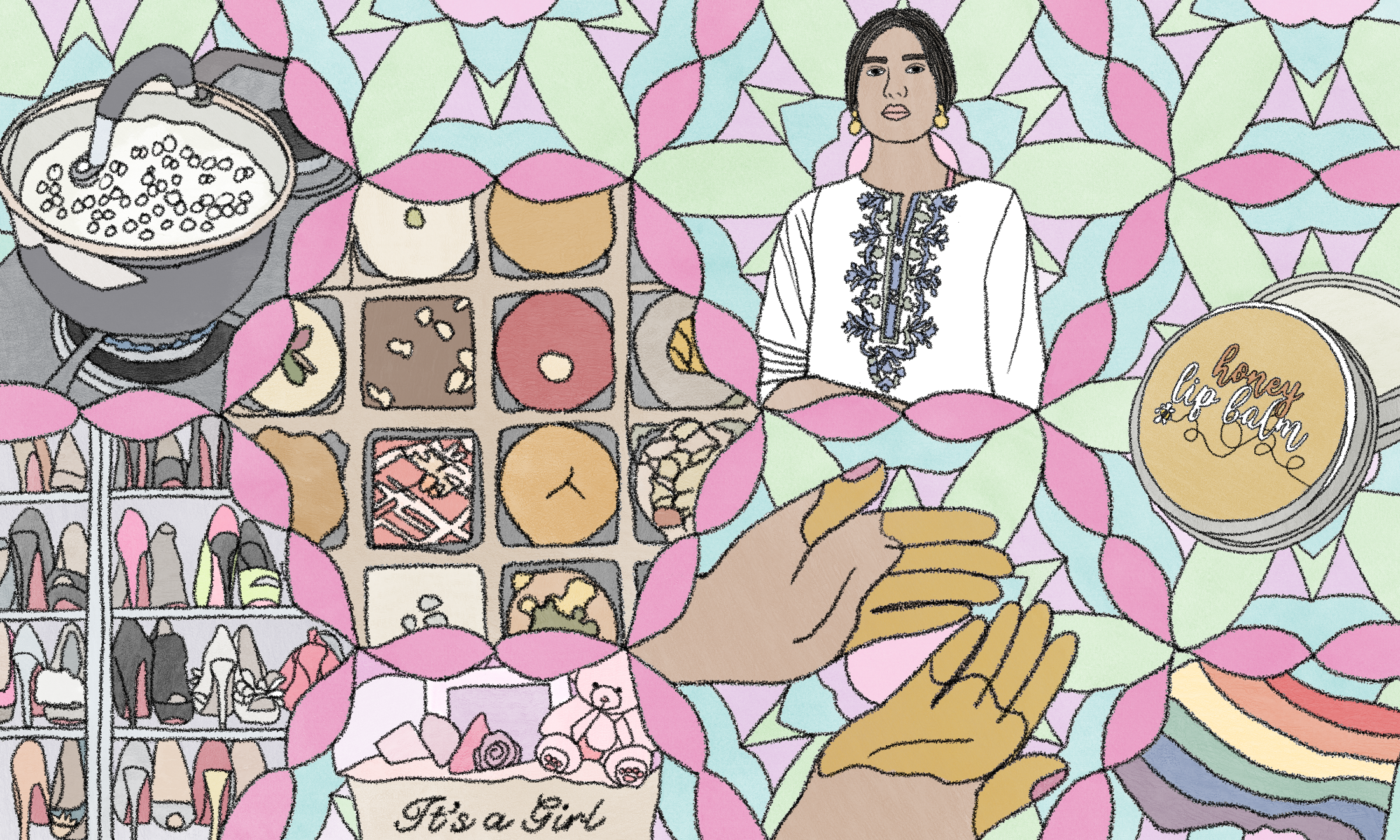

When it was Eid, my mother and aunties would roll up the sleeves of their shalwar kameez while spending hours cooking, yet the men always ate first but never seemed to help clean. My older male cousins would wander off to the garden and come back later with mysteriously glazed eyes, their increased appetites and giddiness would be shrugged off whilst I got reprimanded for my bra straps showing.

When I was nine, I sat with syrupy fingers eating a box of mithai that my mum had given me. It had been gifted because someone had given birth to a boy, which was apparently cause for celebration. It never seemed to happen when the baby basket that left the hospital was pink. These daily slithers of heteronormativity and the double standards that tinge many brown households are subtle acts of subjugation that not only hinder equality but also make sexual self-actualisation and ‘coming out’ even more daunting. All of this affirmed to me my lowly position in the gender hierarchy and my stomach filled with dread at the thought of being subordinate not only because of my sex but also my sexuality.

Growing up as a Scottish, Pakistani queer woman has an accumulation of hurdles that can make life more testing than the average individual’s. However, throwing in the complex element of religion, specifically being Muslim, made things exhausting and alienating in more ways than I ever anticipated. For starters, the amount of queer South Asian representation is deeply limited, even with my favourites such as Tan France or Jameela Jamil often being English or American. Regardless, when Jameela came out, the impact it had on me was tangible. A feminine, queer South Asian whose skin bore the same shade of melanin as my own, who was outspoken as hell and had significant social leverage? You bet I was proud to see it.

“Throughout my teenage years, being anything other than straight wasn’t even a possibility in my brain”

For me, it wasn’t just the trials and tribulations of unlearning internalised homophobia or tackling the battleground that tends to be lesbian dating; it was also the shock factor of how strenuous it was to find someone who accepts me while also accepting the romantic restrictions that came with not being fully out to my family, without fetishising me or being tone deaf in their response. I’ve had everything from being called ‘caramel coloured’ to an ex telling me she now specifically watches brown pornstars because they remind her of me and overhearing her father say the word ‘p*ki’ on the phone. Delightful, I know. The hints of racism that have bled through numerous occasions have often hit home as a stark reminder of how taxing interracial dating can be, even within another marginalised community.

Throughout my teenage years, being anything other than straight wasn’t even a possibility in my brain. When I was in secondary school, a predominantly white environment which filled my parents with dread at the whitewashing that was to ensue, my mother made sure to drill into my head that bringing home a white boy was never going to be accepted. The emphasis on the assumption that it could only be a boy that was the focus of my teenage desires made me align my rebellion towards just that. Thus, the textbook route of heteronormativity fully kick-started and my virginity was soon misplaced into the hands of an obnoxious, wannabe Mo Farah that I tossed notes with during English.

“You can have turmeric-stained hands whilst also waving your rainbow flag, one box doesn’t need to be sacrificed to hold space for another”

My honey lip balm-flavoured kisses continued to land on roughly shaven, cologne slathered faces up until university. Being extremely femme often made me liable to the theory I was hetero, meaning most of the attention I received was from cis men. I was unaware that I could feel the way I did without being invalidated because I didn’t fit into your typical wlw stereotype. This, combined with family expectations and my innate desire to secure my worth through the male gaze, made me mistake enjoying validation for genuine attraction. This delayed awareness affected my sense of self and triggered me into feeling like I had ‘wasted’ years entertaining lacklustre interactions with men due to conforming to the expected social and cultural scripts.

However, I’m 22 now, it’s been four years since I’ve stepped my heels outside the closet, and I embrace my queerness wholeheartedly. Admittedly, I still have the occasional moment where I get pangs of unease or shame but it’s nothing that can’t be worked on. My feelings towards compulsive heteronormativity remain unchanged – it frustrates me to no end, and I think expected behaviour ascribed to gender roles is exhausting, damaging and plain archaic.

Listen, I don’t expect to put my eye to the microscope lens that is examining my community and see that overnight it’s become a kaleidoscope of complete queer acceptance that’s also banished any remnants of heteronormativity. What I think is more realistic, is to continue increasing education on these topics, for uncomfortable conversations to happen and for more queer south Asians to be naturally interjected into the media while religious acceptance is deeply encouraged. You can have turmeric-stained hands whilst also waving your rainbow flag, one box doesn’t need to be sacrificed to hold space for another and most importantly, remember to prioritise your safety and sanity above all else.