Photography via Unsplash/charlesdeluvio

I’m strolling around Costco with my dad when my phone buzzes. It’s an AirDrop notification: ‘Michael X would like to share a photo’. I look at the image preview and it is a photo of someone’s penis. I decline the image immediately but get another notification two minutes later with another picture of a penis. I look around to see who might have sent it to me, but there are so many people in the busy aisles of Costco that I wouldn’t know where to start.

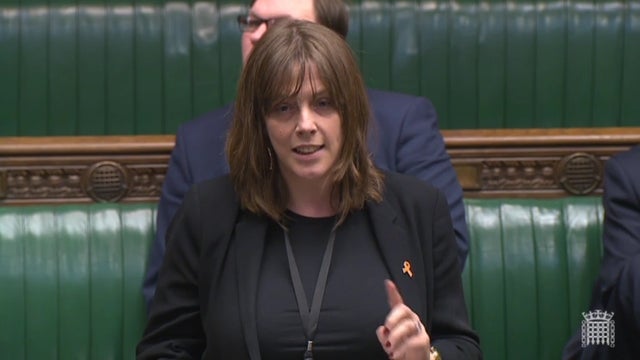

The term for this unsettling and alarming practice is “cyber-flashing”, and this week a government committee recommended that a new law should be introduced to tackle “image-based sexual abuse”. Unfortunately this was rejected by the government and women’s groups have raised concerns that not enough is being done to actually prevent harassment in the first place, and that focus needs to be placed on ensuring children have access to high-quality relationships and sex education (RSE), where they can learn about respect, consent, and building healthy relationships.

My experience in Costco wasn’t the first time that I have encountered this particular form of sexual harassment. I have been sent multiple “dick pics” via AirDrop on numerous different occasions including on the Tube, at a club, and once whilst browsing the homeware section of Marks & Spencers.

“Now when I’m on the Tube, I often worry about being sent a dick pic by a stranger”

The first time it happened I was shocked, and I froze. I thought to myself: what kind of creep thinks it’s okay to send me a picture of their penis without my consent? I have been flashed in person before, but being cyber flashed impacted me more than I thought it would. Now when I’m on the tube, I often worry about being sent a dick pic by a stranger. I have become extremely wary of my surroundings when I’m on public transport.

There is no official definition of cyber-flashing within UK legislation, but Urban Dictionary defines it as “flashing ones private bits via picture message.” Apple’s AirDrop feature allows users to share files including photos and videos between Apple products using both Wifi and Bluetooth connections, in a swift and efficient manner. The feature has three visibility settings: “Everyone”, “Contacts Only” and “Receiving Off”. The default setting is “Contacts Only” and requires both users to have each other’s number saved in order to share files, whereas the “Everyone” setting enables any Apple device users within a 30 foot proximity to send and receive files.

Cyber-flashing is the digital equivalent of traditional flashing or indecent exposure, which is criminalised under Section 66 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003. Sending indecent images is also an offence under the Sexual Offences Act, although if the victim doesn’t “accept” the image, pursuing an investigation is difficult without evidence. Currently, a perpetrator of cyber-flashing could be prosecuted under the Indecent Displays Control Act 1981, however, the law is extremely outdated. In 2018, the House of Commons’ Women and Equalities Committee called on the government to criminalise “image-based sexual abuse”, and proposed a new law which would be based on the victim’s lack of consent and not on perpetrator’s motivation, and would include granting of life-long anonymity for the victim.

The first investigated case of cyber-flashing occurred in 2015. Lorraine Crighton-Smith reported receiving two images of an unknown person’s penis on her phone whilst on a train in South London. The British Transport Police (BTP) investigated the incident, but as Lorraine had declined to receive the image, there was no “technological evidence” for the BTP to work with, and the case was simply recorded as intelligence. “I felt violated,” Lorraine told the BBC at the time. “It was a very unpleasant thing to have forced upon my screen”.

“He sent 10 dick pics in the space of five minutes. I had to get off at the next station, I genuinely felt scared”

As a relatively new phenomenon, research is only starting to scratch the surface of the prevalence of cyber-flashing. A 2018 YouGov study revealed that just under half (41%) of the women respondents had received unsolicited sexual images, and 46% of these women had been cyber-flashed when they were under 18. On an informal Twitter poll I conducted in April 2019, 13% of 566 respondents confirmed that they had received unsolicited images, which equates to 73 experiences of cyber-flashing specifically. One woman, Sara*, explained:

“I was on the tube and it was just me and one other man in the carriage. I repeatedly kept getting notifications of someone sending me a dick pic…I knew it was him, ‘cos he was the only other person there. Like, he sent it 10 times in the space of five minutes. I had to get off at the next station, I genuinely felt scared… I could feel him staring at me.”

Since the incident, Sara hadn’t used her AirDrop. She explained that a friend’s comments made her feel like it was her fault for not having tighter security settings on her phone:

“I’m too careful now. You can’t trust anyone. I refuse to be in a carriage by myself with another man. I felt violated… the guy was clearly getting a kick out of it […] I told my friend about it and she started questioning me as to why my AirDrop setting was on ‘Everyone’. Imagine I told another person and he said I must have done something to make him send it…what the hell.”

Another respondent tweeted: “How was I on the bus, and the guy behind me sent me a dick pic. I knew it was him immediately ‘cos he was cracking up. I remember telling him what the f***. Everyone else turned a blind eye.”

Currently, the only country to have criminalised cyber-flashing is Singapore, as part of a major crackdown on sexual harassment online. Newly approved criminal law means that anyone found guilty of sending “unsolicited images” could receive a sentence of up to two years. However, concerns have been raised that new legislation relating to online and digital security in Singapore is being leveraged for political means, to curtail free speech and quash dissenting opinions.

A few online petitions have begun to circulate, calling for the criminalisation of cyber-flashing in the UK, but women’s organisations working on gendered violence have argued that criminalising forms of abuse will not solve the issue. Speaking to the BBC last month, Rachel Krys, co-director of End Violence Against Women Coalition explained that safeguards must baked into technological developments, and that tech companies must “think about women and how [new software] could affect them”.

Small shifts are being made in this arena: Facebook have changed the format of the Messenger function on their platform for younger users. Facebook now blocks incoming messages from anyone not on an under-18 user’s friends list, which goes some way to preventing them from viewing unsolicited sexual images from strangers. So far, Apple have chosen not to respond to the issue of cyber-flashing, and have failed to comment on suggestions that the “Everyone” setting be completely removed from AirDrop, so users can only receive images from known contacts.

I shouldn’t have to change how I use my phone in order to protect myself. I’m not willing to accept blame for receiving a disgusting image, and it’s unacceptable to expect survivors to adjust their behaviour to accommodate for the actions of harassers. Instead, focus must be placed on teaching people not to abuse phone features and not to send unsolicited sexual images; this is long-term work, which must be steered by experts in gendered violence, and should be funded by the government as part of their priority to end violence. Cyber-flashing marks a new frontier for technology-based abuse. Without serious commitments across government and industries, digital sites of harm available for exploitation by perpetrators will only continue to run unchecked.

If you have experienced abuse or harassment, you can access free confidential and non-judgemental support in the UK via the Women and Girls’ Network. Information about other support services is available here.We also recommend checking out Hollaback, a global network of organisers working to end sexual harassment through delivering training and community support.

If you are a victim of cyber- flashing in the UK, and it is safe to do so, you can contact the police or the British Transport Police on 0800 40 50 40 or text 61016.

*names have been changed to protect identities.