5 British Black Panther women whose names you should know

We shouldn't fail to acknowledge the admirable contributions and labour of black British women in resistance movements – including the Black Panthers.

Zahra Dalilah

21 Apr 2017

Photography by Neil Kenlock

John Ridley’s Guerilla came under understandable fire after it aired, as viewers questioned why the dramatisation of the activities of the Black British Panthers in the 1970s featured no black women in leading roles. Those versed in this period of resistance were quick to point out that de-centring the role of black women was simply ahistorical. In Kehinde Andrews’ words, “Black women weren’t just part of the history of the black power movement; they led it in Britain.”

Disappointment also resounded as, by writing black women out of history like so many before him, John failed to acknowledge the relentless and admirable contributions of black British women in resistance movements. TV dramatisations aside, luckily there are other resources that we can reference to remind ourselves that black British women have been slaying from day and treading truly heroic footsteps that for us to follow in.

Here are five badass Black Panther women whose names we should all know and never forget.

Olive Morris

Founding member of one of the most important black feminist organisations of the 1970s, OWAAD, Olive Morris was a Jamaican-born activist who was truly revered amongst her peers. Enduring brutal police violence as a teenager, Olive was politically active before she was a legal adult. She joined the Black Panthers Youth branch as a teen and went on to fight racism and police brutality in Brixton for almost a decade.

Following the Panthers’ demise, Olive established the Brixton Black Women’s Group, a collective of radical feminist black women who took action on issues which specifically affected black women, such as immigration and family planning and founded the Brixton Black Women’s Centre in Stockwell Green.

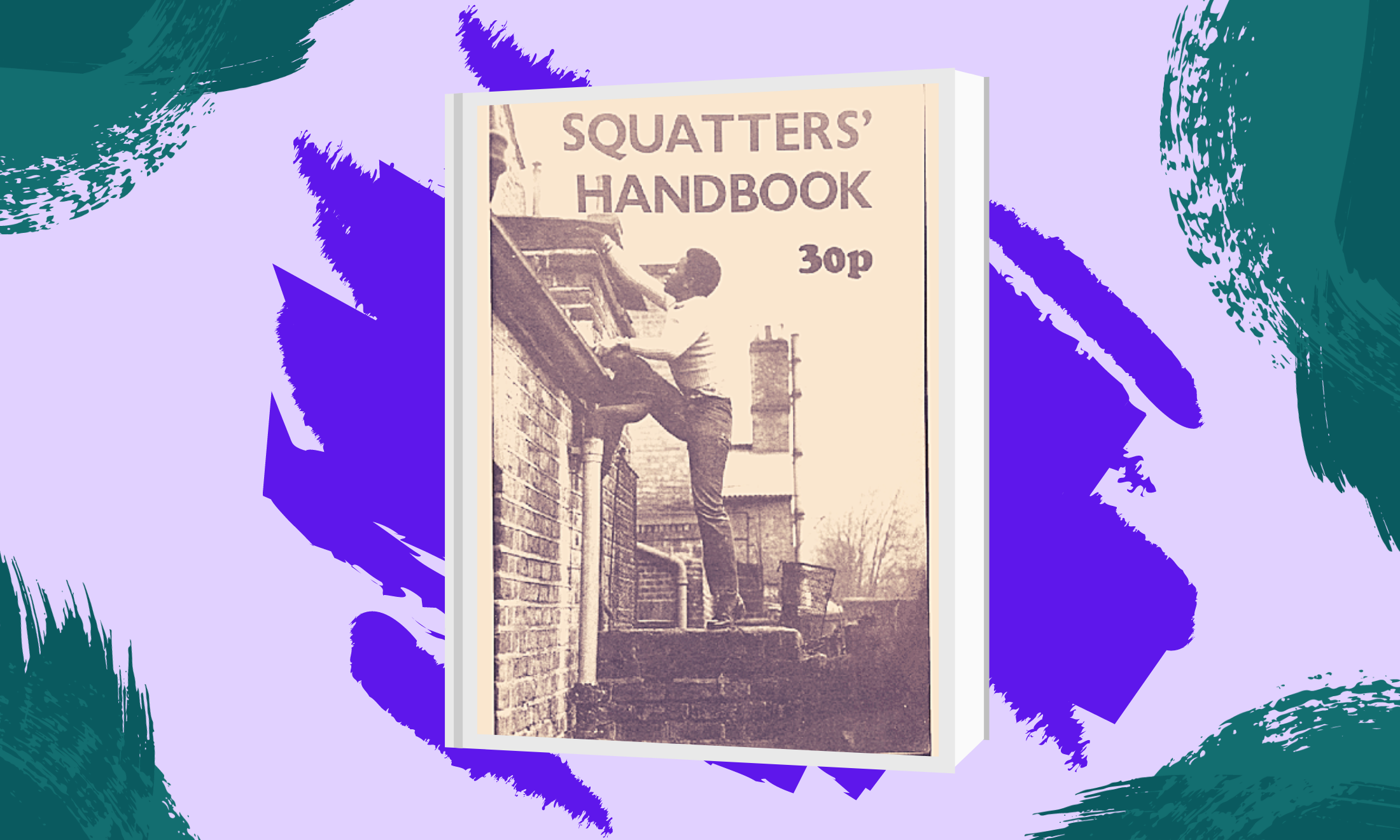

Prominent in the black squatting movement, Olive was responsible for securing some of the most crucial spaces for the black power movement including, the offices of the journal Race Today and of the Brixton Black Women’s Group. Still today on Brixton Hill, you can find the Olive Morris House, a building owned by Lambeth Council, which was constructed in 1986 a few years after her untimely death. She was only 27.

Altheia Jones Lecointe

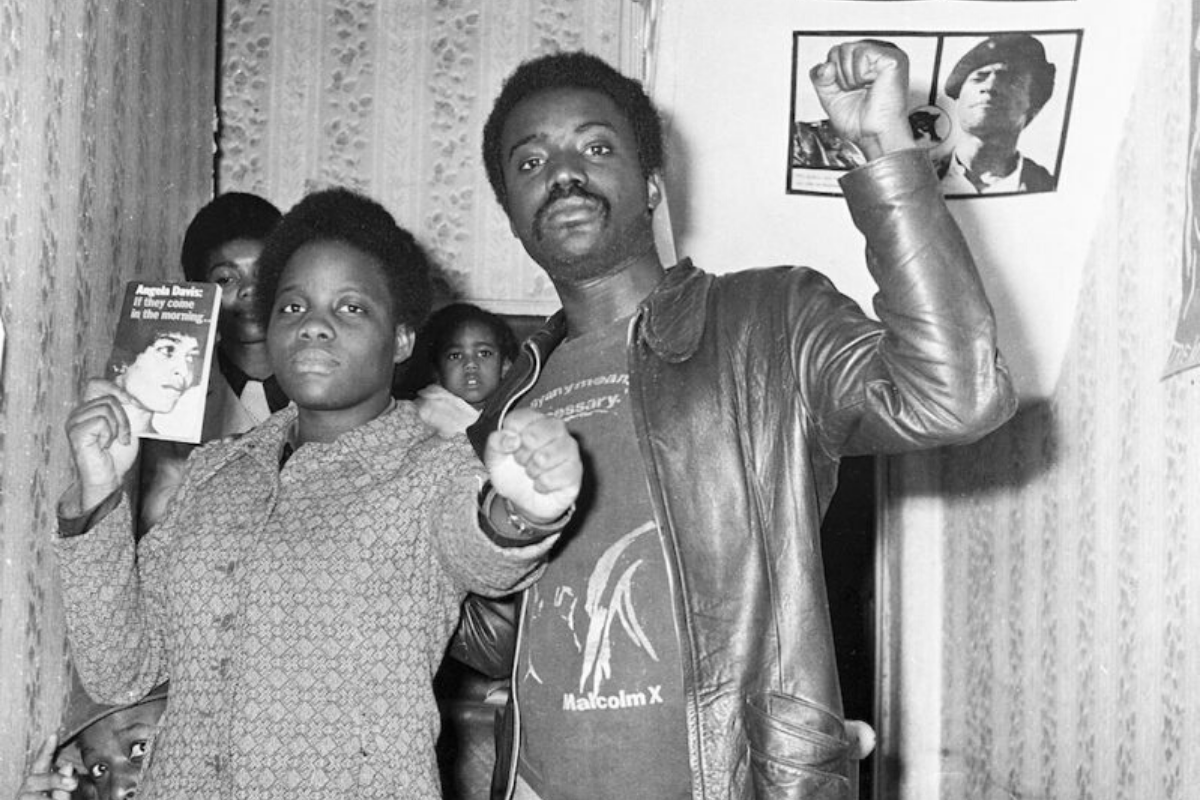

Trinidad and Tobago native Altheia Jones-Lecointe, was largely considered the leader of the Black British Panthers in the early 1970s. Not just the leader of the women’s section, but the leader of its 3000-odd members.

Altheia was also one of the Mangrove Nine, whose arrests and subsequent acquittal achieved the first judicial acknowledgement in the UK that there was “evidence of racial hatred” in the Metropolitan police. They were arrested at a protest against the racialised attack on the restaurant and community hub the Mangrove, which had endured 12 raids over the course of 18 months, despite no proof of criminal activity on the premises.

This was huge at a time where institutional racism with the police force was far from a household concept. The nine’s extraordinary legal success is largely credited to both her and Darcus Howe’s decision to defend themselves in the trial and dismiss 63 jurors who they deemed unfit to bring about a fair trial (read: probably kinda racist).

The film The Mangrove Nine, written by John La Rose, was released in 1973, two years after the trial.

Elizabeth Obi

Founder of the Remembering Olive Morris collective, Elizabeth (Liz) Obi worked closely with Morris from 1972, both in the Black Panthers and in founding the Brixton Black Women’s Group.

Together, they successfully squatted the headquarters and set up the organisation from scratch. Speaking on Guerilla’s first episode, she celebrated the inclusion of the character based on Mala Sen (played by Freida Pinto) but called the portrayal of black women in it “unforgivable”.

Beverley Bryan

Activist and author, Beverly Bryan was active in the Black British Panthers from around 1970. Alongside Olive Morris and Liz Obi, Beverley helped set up the Black Women’s Group as they took on education, police brutality and housing together.

Beverley co-authored The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain, published by feminist publishing house Virago. The book documented the history of black British feminism in the 1970s and went on to win the Martin Luther King Award in 1986. She later moved back to Jamaica where she became a Professor at the University of the West Indies.

Leila Hassan Howe

Leila Howe, born Hassan, edited the journal Race Today from 1986, having been a core member of staff since its inception. Growing up “a devout practitioner” of Islam in East Africa, Leila similarly became involved in the black power movement in the late 1960s, co-running the Race Today offices that Olive Morris had secured where they would run Basement Sessions, discussing art, culture and politics, much of which would later feature in the magazine.

Race Today published sixteen books between 1977 and 1988 as well as a monthly magazine which sat at the forefront of black radical thought from 1973 – 1988.

***

All five of these women are worth remembering for their contribution to bettering the black British experience and facilitating better lives for generations to come. That they are “forgotten”, erased or unacknowledged is not a statement of fact but a temporary predicament.

As Beverley wrote herself into history and Liz Obi continues to write Olive Morris into history so must we continue to say their names, engage with the work and above all else, write ourselves into history too.

This list is by far exhaustive of course, and honourable mentions should go to Barbara Beese, Gail Lewis, Stella Dadzie, Hazel Carby, Jessica Huntley, Claudia Jones, Amy Ashwood Garvey, Amy Jaques Garvey, Una Marson, Adelaide Casely-Hayford and countless other black women who have collectively or otherwise shaped the Britain that we live in and constructed the boots that we attempt to fill today.

Special thanks to my mother, my sister (@AbenaKJohn), Black Twitter and the Black Cultural Archives, the best resources I have known when researching Black British history (check out @SelinaNBrown, @lolapaak and @lmartods for some legit history lessons). For more detailed information about the Black Panthers, check out the work of scholars like Frankie Harding, Rob Waters, Ann-Marie Angelou or W. Christopher Johnson.