Missy Kel/Flickr

As Palestinians are denounced for stone throwing, we ask: why is passive resistance so idealised?

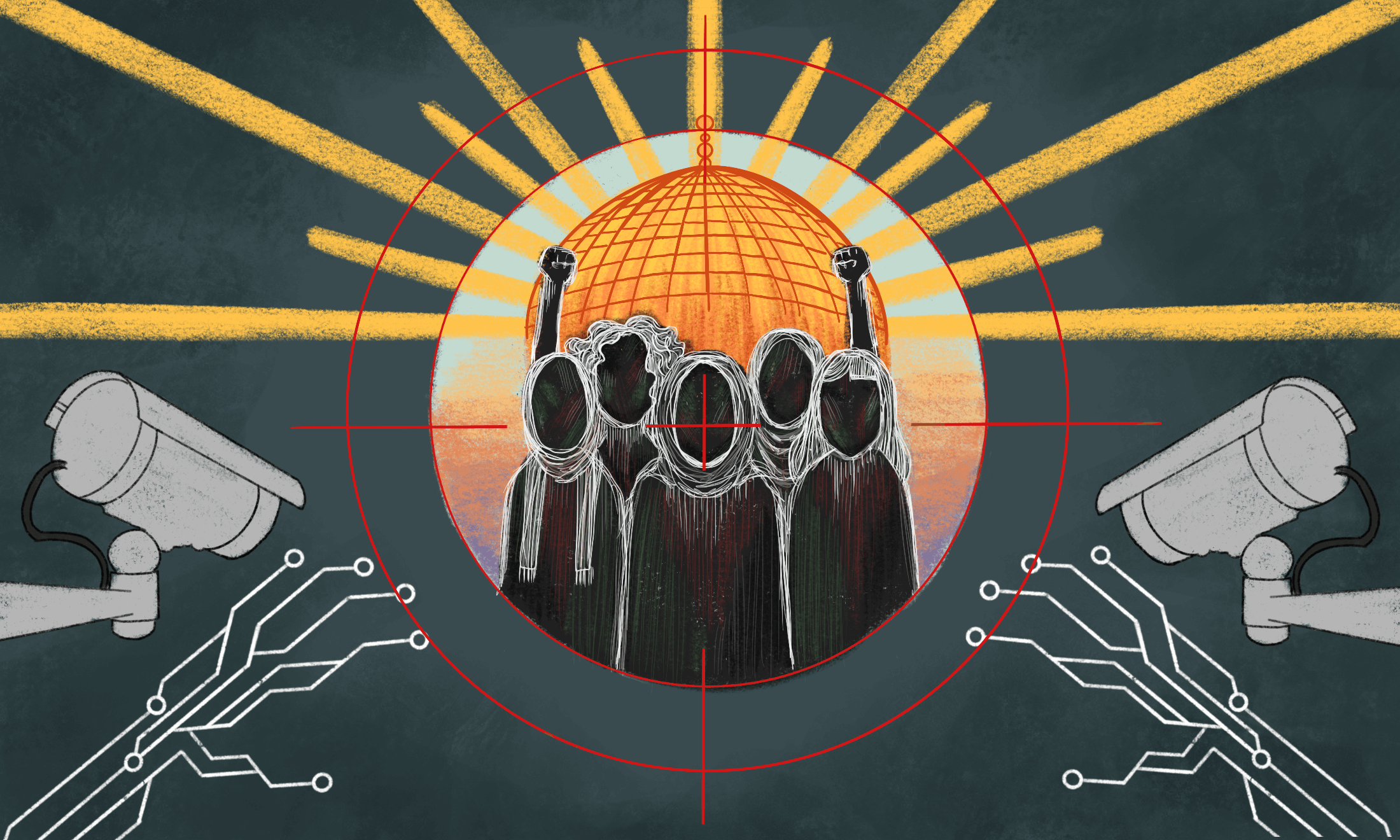

Israeli forces have used resistance from Palestinians as justification for a brutal crackdown. But what does completely 'peaceful' protest achieve?

Khadijah Hasan

21 Jul 2021

When Palestinian protests broke out in June, after the illegal occupation of the Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood in East Jerusalem, the world watched in horror as the Israeli state acted both antagonistacally and responded to Palestine resistance with disproportionate force. At the climax-point of aggression, UN figures estimate that 219 Palestinians were killed due to Israeli air strikes. But in the midst of the arrests and brutality, a number of onlookers seized upon a seemingly minor incident: the throwing of stones at the IDF by some Palestinian demonstrators.

Headlines such as “Rock-throwing Palestinians clash with cops outside Al-Aqsa mosque” characterised Palestinians as aggressors, helpfully failing to reference any weapons that might have been used by the ‘cops’ in the first place. Other examples also foregrounded stone-throwing, with one headline announcing that “Muslim protesters barricaded themselves inside the mosque while hurling stones and fireworks at police” and another stating:“Palestinians hurled rocks at Israeli officers in riot gear who fired rubber bullets, stun grenades and tear gas”. Context is removed; instead the actions of Israeli forces are framed as a necessary response to Palestinian protest, which has been ‘delegtimised’ because it involves physical resistance. In contrast, an example of completely passive Palestinian resistance, that has been framed positively by the media, is the use of ‘watermelon’ imagery by artists such as Khaled Hourani.

It all harks back to an age old question: why is passive protest so lionised?

“The actions of Israeli forces are framed as a necessary response to Palestinian protest, which has been ‘delegtimised’ because it involves physical resistance”

From childhood, people in the Western world are taught that there is a ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ way of protesting or challenging the state. In countries like the UK and America, and even places beyond the West, such as India, school history books celebrate the peaceful sit-ins of the US Civil Rights Movement and Mahatma Gandhi’s ideals of ahimsa (non-violent resistance) against colonial rule. These are the unequivocal heroes, we are told, while legacies left by the likes of Malcolm X – who at first decried passive resistance – and the Black Panthers are remembered as ‘controversial’ and ‘complicated’.

But is this a whitewashing of history on behalf of the status quo? In a recent reading of The Patient Assassin by Anita Anand, I was surprised to find out that resistance efforts in colonial India were not as non-violent as we are taught via the British curriculum. The Ghadar (revolt) movement stated in their first 1913 publication that “the time will soon come when rifles and blood will take the place of pens and ink”.

A 2020 study of non-violent resistance by academic Alexei Anisin debunked the idea that non-violent or passive action against the state is the most effective. Instead, his work found that resistance involving “reactive, unarmed violence” – self-defence as a reaction against an aggressive state power – and “unarmed violence” – direct action such as “usage of stones, rioting, sticks, car burning” – had greater rates of success. ‘Success’ here is defined as whether the resistance in question were able to achieve their demands. Analysis of 396 political campaigns taking place between 1800 to 2006, showed that completely non-violent campaigns experienced a 48% rate of success. In comparison, campaigns involving unarmed violence and reactive unarmed violence had success rates of 61% and 60%, respectively.

The findings contradict earlier research conducted by Harvard professor Erica Chenoweth where analysis of 323 violent and non-violent resistance movements seemed to suggest that non-violent movements led to longer-term changes. Anisin refutes this conclusion, assessing that the data set used by Chenoweth was not accurate and many campaigns labelled ‘non-violent’ actually consisted of unarmed violence – like rock throwing.

Context is incredibly important when considering this. Many of us believe that engaging in passive, non-violent protest means we have a moral high ground. However, we have to accept that choosing non-violence in many contexts is a privileged route to pursue. When the state is already pursuing violence through systems and policies, is it not irrational to expect there to be no reactive or unarmed violence?

Unsurprisingly, we are taught that the ‘right’ way to dissent is the one which causes the least harm to the state. To quote the American anarchist activist Peter Gelderloos, “nonviolence ensures a state monopoly on violence”. Effectively, victims of state brutality – who are often already victimised due to identity characteristics such as race, religion, etc) are “counselled against responding with violence because that would justify the state violence already mobilised against them”. This immediately sets up an unequal power dynamic, framed by the state and a compliant media as a situation which justifies continued state violence, creating a cycle of continued oppression.

“We must remember it is in the interests of the state to immediately discredit resistance movements and to equivocate acts like stone throwing with hundreds of trained and armed soldiers storming a place of religious worship”

Completely passive resistance also doesn’t receive any exemption from state crackdowns. Throughout history, ‘peaceful’ protests and resistance have been met with brutal, vicious force. A harrowing example is the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre in Amritsar, India, which took place in 1919, where unarmed civilians celebrating the festival of Baisakhi were indiscriminately murdered by colonial British troops in an act of extreme violence. The final death toll was estimated to be at least 1000. At the time, public gatherings of any kind had been banned to prevent collective action. If an oppressive and powerful state feels threatened, the response will not discern between protestors that are ‘violent’ or ‘peaceful’ – the aim is to crush all resistance. We can see it everywhere, from fatal violence inflicted on demonstrators in Myanmar today, to historical records of the Peterloo massacre of 1819.

It’s shameful that passivity on behalf of those resisting is still idealised when cases like the above show that state-sanctioned violence will always occur. And as history has shown us, accountability for the state’s actions are rare and never substantial. In the wake of the latest chapter in Palestine’s struggle, we must evaluate how passive resistance is portrayed and how dominant powers seek to delegitimise any form of protest that poses an actual challenge. We must remember it is in the interests of the state to immediately discredit resistance movements and warp the presentation of power dynamics to equivocate acts like stone throwing with hundreds of trained and armed soldiers storming a place of religious worship.

Passive resistance is favoured by the state because it upholds its power. We must never fall into the trap of adhering to respectability politics and meekly bend our heads when they tell us to. Protest is not meant to fall in line.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?