Courtesy of Lionsgate

Most coming-of-age films zone in on an adolescent struggling to find themselves. Someone trying and failing to belong. Adewale Akkinuoye-Agbaje’s directorial debut, Farming, gets to the heart of this through an off-kilter snapshot from his own life. In this gritty drama our protagonist Enitan, Adewale’s fictional alter ego, is riddled with an anxiety to blend in which sees him take the unusual step of joining a group of neo-Nazi skinheads in Tilbury, Essex in the 1980s.

Being a member of the Commonwealth meant that people from Nigeria were, and still are, encouraged by the British government to come to the metropole as students and labourers where they face a myriad of issues –from racism to financial instability. In the film, Adewale plays one of the parents of Enitan, alongside Genevieve Nnaji as Enitan’s mum. Like Adewale’s birth parents, Enitan’s parents came over to Britain to study accountancy and law in London.

Heartbreakingly, to pursue their careers, they give him away as an infant to be raised by a white-working class “gypsy” family in Tilbury. Many Nigerian families were forced to make the same difficult decision when struggling to raise a child. This process would later be termed “farming” by British social workers – the practice of predominantly Nigerian parents, who had birthed children in the UK, giving their children away to white-working class families to take care of.

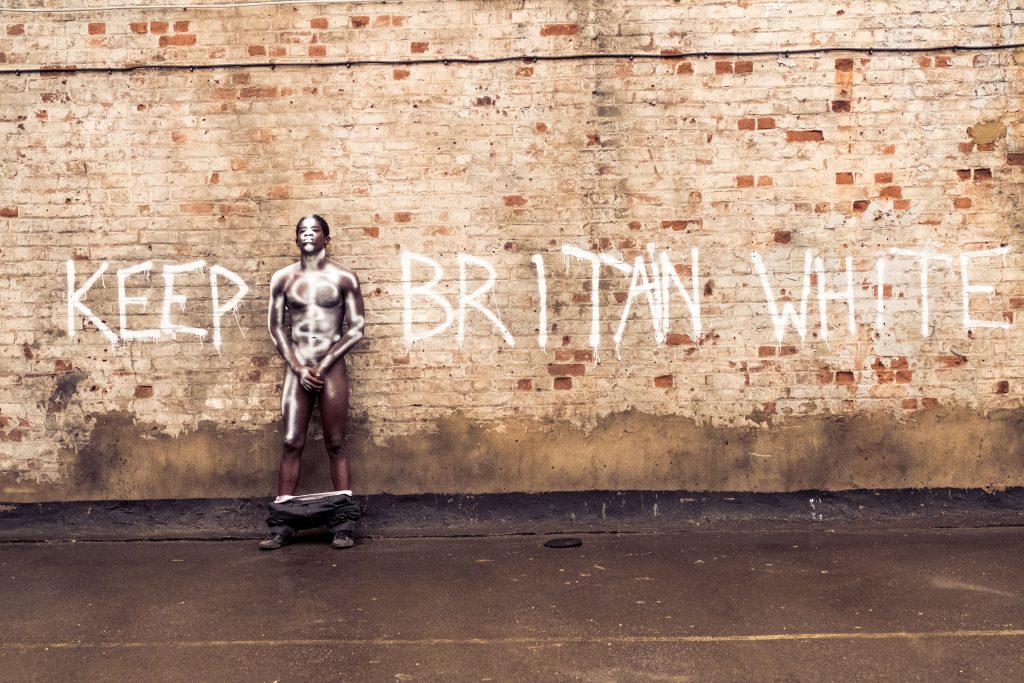

Despite the scarring events, speaking to Adewale over the phone, he says he feels that the entire process of writing and releasing the film felt really “cathartic”. It meant he had to mentally revisit his memories of Tilbury (a place still plagued by poor race-relations), a hostile home. Young Enitan is routinely verbally and physically abused by his white neighbours. As Adewale explains, in 70s and 80s Britain racial slurs were a “part of everyday conversation”. Television shows like Love Thy Neighbour, a comedy-drama focused on the relationship between a fictional black couple and their racist white neighbour Eddie, and popular comedians like Jim Davidson played on tensions and popularised the usage of the slurs “nig-nog”, “wog” and “coon”. In this climate, being black and British meant having to constantly confront explicit racial abuse.

Enitan’s life in Tilbury is abruptly interrupted when he turns eight and his birth parents abruptly return and take him to live in Nigeria. That made Enitan one of the lucky few Nigerian foster children living with white families. Adewale explains: “The foster home that I was sent to there was at one point up to nine or 10 other children within the house and there were up to 50 children in my [foster] parents’ house throughout their lifetime. Several of the parents never returned for their children. They just abandoned them.”

Even though by moving to Nigeria Enitan no longer has to experience being a visible minority, the film does a good job at showing how his experiences here caused even more trauma. His birth parents force him to undergo Yoruba scarification to help protect him and bind the his spirit to their homeland.

“The essence of the story is extremely true and really just skimming the tip of the iceberg”

Adewale Akkinuoye-Agbaje

However, with no explanation as to why he is undergoing such a painful ritual Enitan is left so afraid that he becomes mute for six months. Afraid of him becoming a “dullard” his Nigerian parents decide to send him back to his white foster family in Tilbury. With these dramatic upheavals, Enitan has an identity crisis, rejecting his black identity, and tries to become white, covering his face in talcum powder in a gut-wrenching scene reminiscent of a young Sandra Laing covering her skin in bleach in the 2008 film Skin.

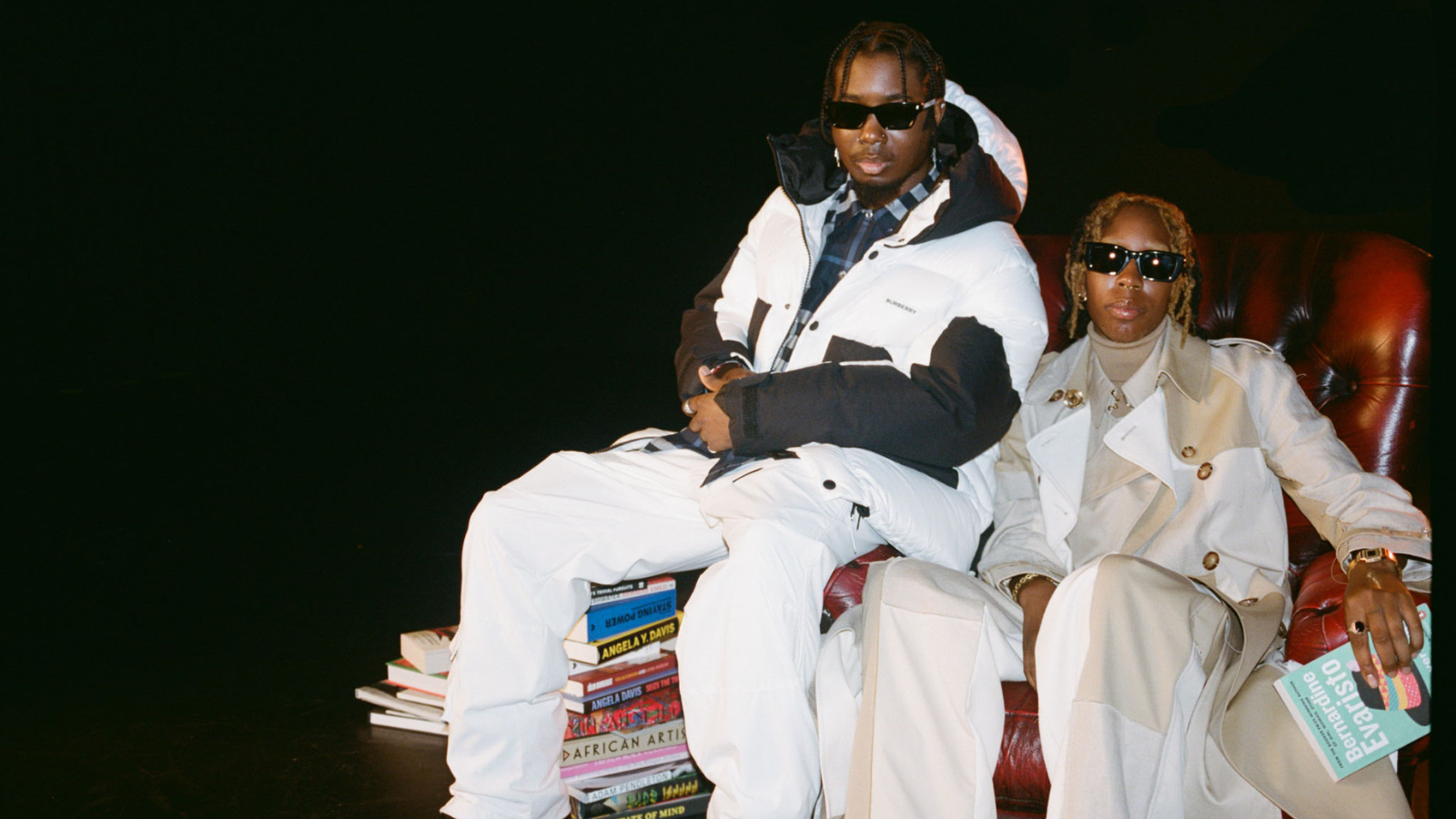

Teen Enitan, portrayed as Damson Idris, still living in Tilbury, gets drawn into the local skinhead gang, who would at rare intervals give him the scraps of friendship that he so craved. “It was part of the culture at that time. You had two choices… You were either going to be a victim or the oppressor,” explains Adewale, who also joined a skinhead gang as a teen. This is the story the film spends the bulk of its hour and 41 minutes exploring. It’s a sad, but deeply compelling watch, although the film does end on a note of hope.

While Adewale makes clear that there is some artistic licence in the film, it’s shocking how much is true to life. “The essence of the story is extremely true and really just skimming the tip of the iceberg,” he says.

Adewale started writing this film over 14 years ago whilst acting on the TV show Oz (around the time he took on the role of Majestic in 50 Cent’s Get Rich and Die Tryin’ movie). Both major US-based roles. While black British stories are now increasingly being released to both domestic and international audiences (Shola Amoo’s The Last Tree, which also centres on “farming” is currently out in cinemas), up until very recently many depictions of British life and history on-screen completely erased black people from the narrative.

“We here in Britain are very familiar with the African-American experience, even the West Indian experience in migration but very little is known of the African experience in migration to Britain,” Adewale says. It’s fitting therefore that the film has been released during Black History Month. Adewale wants us to more to be aware of the experiences of what he calls the “first black British generation to be born on British soil”. It is his hope that with this film the experiences of British-Nigerians will be recognised and will never be a “footnote” within British history.

“When all of a sudden you get recognised for something else, when [the skinheads] started to call me my actual name, other than the slur, that became a lifeline”

Adewale Akkinuoye-Agbaje

Issues of representation are important to Adewale, so much so that he ensured that the Yoruba language was spoken in the film. Casting Genevieve Nnaji, whose own directorial debut Lion Heart recently became the first Nigerian film to be nominated for an Oscar, as the mother in Farming was another deliberate decision.

“[Accuracy] was important in depicting the African sequences in Nigeria. We got a real Nigerian band to play, real drummers to come in. Whenever depicting elements of my culture it had to be very authentic,” he says. “Directors in Nigeria sent me footage from Lagos because it was important we felt what Lagos was like, on the streets on the roads and if I couldn’t do it myself a Nigerian director could send me footage that they would shoot for me. To be able to bring an understanding of our culture through the eyes of one of us is really important.”

While many of us will never know what it was like to be a British-Nigerian in 70s and 80s Tilbury many of us do know what is like to be a “minority in a predominantly white society”, as Adewale recognises. He commiserates with me as we both discuss the similar frustration we felt with having our names purposely mispronounced in school, with him growing up with the name Adewale in the 1970s and me growing up with the name Oluwaseun in the 2000s. Many of us know what it is like to be the only person who looks like you in the room and how you may laugh along with racist jokes to fit in because, as with Enitan and the skinheads in Farming, sometimes it seems “easier to fit in than to go against”. It’s only upon reflection you see how toxic that dynamic is.

As Adewale explains it: “When you’re constantly subject to racial slurs, degrading imagery and racial abuse and you don’t have any black role model to empower you to say you’re black and you’re beautiful you suddenly begin to identify with the derogatory terms. When all of a sudden you get recognised for something else [his fighting skills], when they started to call me my actual name, other than the slur, that became a lifeline. You just want to keep that coming so that they don’t return to calling you the racial slurs”.

And, what of his own troubled family dynamic? Before writing the film he was able to cultivate a better relationship with his biological parents, and by stepping into the role of his father in the film he was able to better understand where his parents were coming from. At different points in the film references to rainbows are made. This “undercurrent” within the film is a nod to his parents fruitless searching. Was coming to England and giving their son away going to result in a better life for either of them. was it worth what they were “giving up”? Or were they “chasing rainbows”, which all eventually disappear?

By confronting the pain in his past he’s finally reached clarity. After all, he’s had “30 years of distance” from the events so it had actually been healing.

He adds: “It seems to have formed a collective therapy for those that have experienced the farming process because whilst I was in production people were sending in stories of their own… which we tried to honour in the film. It’s created some really wonderful, insightful dialogue with the audiences.”

Farming is in cinemas now