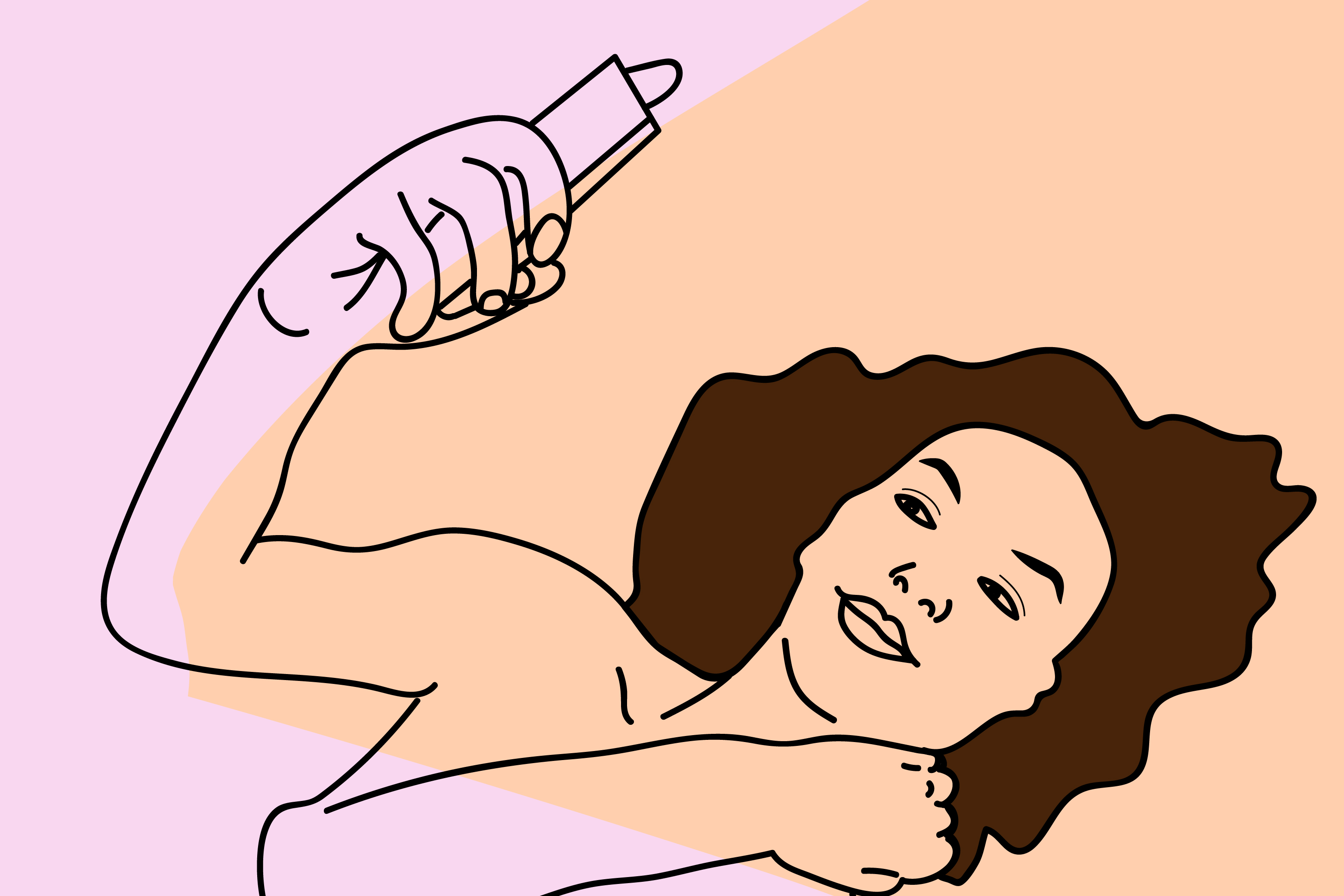

I’m lying flat on my bed. My sheets are white, a little grubby, but no more than those of any other twenty-something living in the city, indoctrinated into the cult of “I’m too busy to look after myself properly”. There is a cold light outside, it’s late August and sunny, but the positioning of my room means it’s usually bathed in shadow in the morning. The sun, refracted through my blinds, is casting a pleasingly angular sun-shadow pinstripe down the middle of my chest. I smile and CLICK. It’s done. My first naked picture.

My first naked selfie, no less. I never thought I would be one to take photographs of myself – especially not naked – yet here I am after years of being exposed to the exploits of those with many more followers than me on Instagram. Sure, I’ve taken pictures of my face before, and I’ve even photographed a discombobulated breast or two. Those were confined to the archives of a now expired long-term relationship where total trust reigned and in the absence of other conversation, it was acceptable to communicate using pictures of silly facial expressions. But this wasn’t intended to be silly; it was intended to be hot. For distribution to a virtual stranger. My parents would be so disappointed.

“I was to be hidden from them like an albino from sunlight. I was to be shielded from sunlight too, in case I lost my colour”

As a child, I garnered a lot of attention for having much fairer skin than is usual for someone of Bengali heritage. In the brief time that I spent living in Bangladesh, people stared a lot. I was peculiar looking enough that strangers would address questions to my grandparents, usually: “Are her parents foreign?”, but also sometimes “Can I take a picture of her?” This comes up in anecdotes about my childhood but tallies with my own experience. In the dozen or so times I’ve returned to the homeland since leaving aged four, I’ve experienced the same. Or at least, I did, until me being stared at by strangers became so untenable to my parents that I stopped being allowed outside. They became very protective over me. Over what, though?

It wasn’t exactly a concern over my safety, although that exists too. It was a protectiveness over my appearance. They explained their superstition to me on one occasion: the more gazes that fell upon my “beauty” (cringe), the less it would become. Their worry wasn’t that of the danger that might arise if I received attention from the wrong kind of stranger. The danger was in the power of the looks themselves. However fleeting, each one could sap something intangible. Even through a car window, which is why I always had to sit in the middle seat. I was to be hidden from them like an albino from sunlight. I was to be shielded from sunlight too, in case I lost my colour.

“The perverse pride of having an atypical skin colour goes unchallenged”

These attitudes indicate the self-loathing, white-washing element of South Asian standards of beauty. Valuing fair skin as an ideal of beauty is unquestioningly accepted in the Bengali communities that I have experienced. Strangers comment on the colour of my skin as soon as they encounter me: ethoh forsa, dekthe bidesi. “You’re so fair, you look foreign”, delivered as a compliment. The perverse pride of having an atypical skin colour goes unchallenged; there is no doubting the view that darker is ugly, nor any scrutiny over where it originated. Like a glorified freak show, strangers want to take photos with me. The price of a ticket is some family connection. You last saw my mother 25 years ago? That affords you one snap, and my mother must be in it. Our house in Bangladesh is replete with the images of the black sheep “white” girl. I am the unlimited resource, a frame of a colonial past, and it continues to shape society today.

These thoughts idly flash through my mind as I lie there. Contrast these attitudes to my picture to me, here now, taking a picture of my relatively milky bare flesh to send to some guy I met on Tinder. Just as once it was protected, here I am willing to bottle it and give it away. With all other acts of rebellion, there is some upside. Sex is healthy, drugs are fun. But what do I get out of sending a dirty picture?

Taking pictures of oneself first got big when I was a teenager and MySpace had its hay day. Overexposed high angled emo shots were the order of the day. Without a digital camera or a webcam (my parents were sensitive about my image even in the UK), I was bereft of the tools required to proliferate my online image.

I passed this off as being unwilling, not unable. “I just think it’s lame how people take pictures of themselves to get MySpace likes.” Soon, social media changed, I got a digital camera, and took many hundreds of boring photos of me and my friends standing in a row drunk with one small bit of context changed to make the picture worth taking. Now, we’ve stripped ourselves back to images only. Despite not being a teenager anymore, two of my most recent Instagrams are photos of me by me. Ten, if you include bits of me that aren’t a face. The idiom says one of those pictures is worth more words than I’ve written in this essay so far. To me, it is a product of boredom, of neediness, of wanting to join in where I couldn’t before.

“Perhaps my parents were right – every gaze drags away a little bit more of what’s good, it cheapens and commodifies”

When you’re unclothed and messaging a stranger, there’s all that and then there’s an intimacy. The confidence that your nipples are worth digitally recording. The trust that they won’t be sent on (but it’s OK if they are, your face is obscured). The desire to close the gap posed by the airwaves, to demonstrate something more than the words that can be meaninglessly tapped out and sent to anyone. The novelty of sharing something private with a stranger. Or, the illusion of it, since I was so proud of my artfully taken nude that I showed it to all my friends.

Perhaps my parents were right – every gaze drags away a little bit more of what’s good, it cheapens and commodifies. Once, for someone to know what you looked like was a privilege, dependent on chance. To know what you looked like yourself meant that you could afford glass for a mirror. Now, it’s so commonplace that there’s nothing worth meeting for. With a little online stalking, you can get a souvenir of the real thing. Should the person consent, you can get a facsimile of their privates, too. But there’s no simulation for a touch or an interaction. Hundreds of Bengali strangers might have a memory of my face, but no idea of voice, cadence and warmth. And this man from Tinder now has a picture of my breasts.