Naomi Gennery

Why despite being arrested during police intervention, I’d do it again

These acts of mutual solidarity can build radical change and find abolitionist alternatives to policing. The more people that intervene, the safer it becomes for all of us to resist.

Anonymous

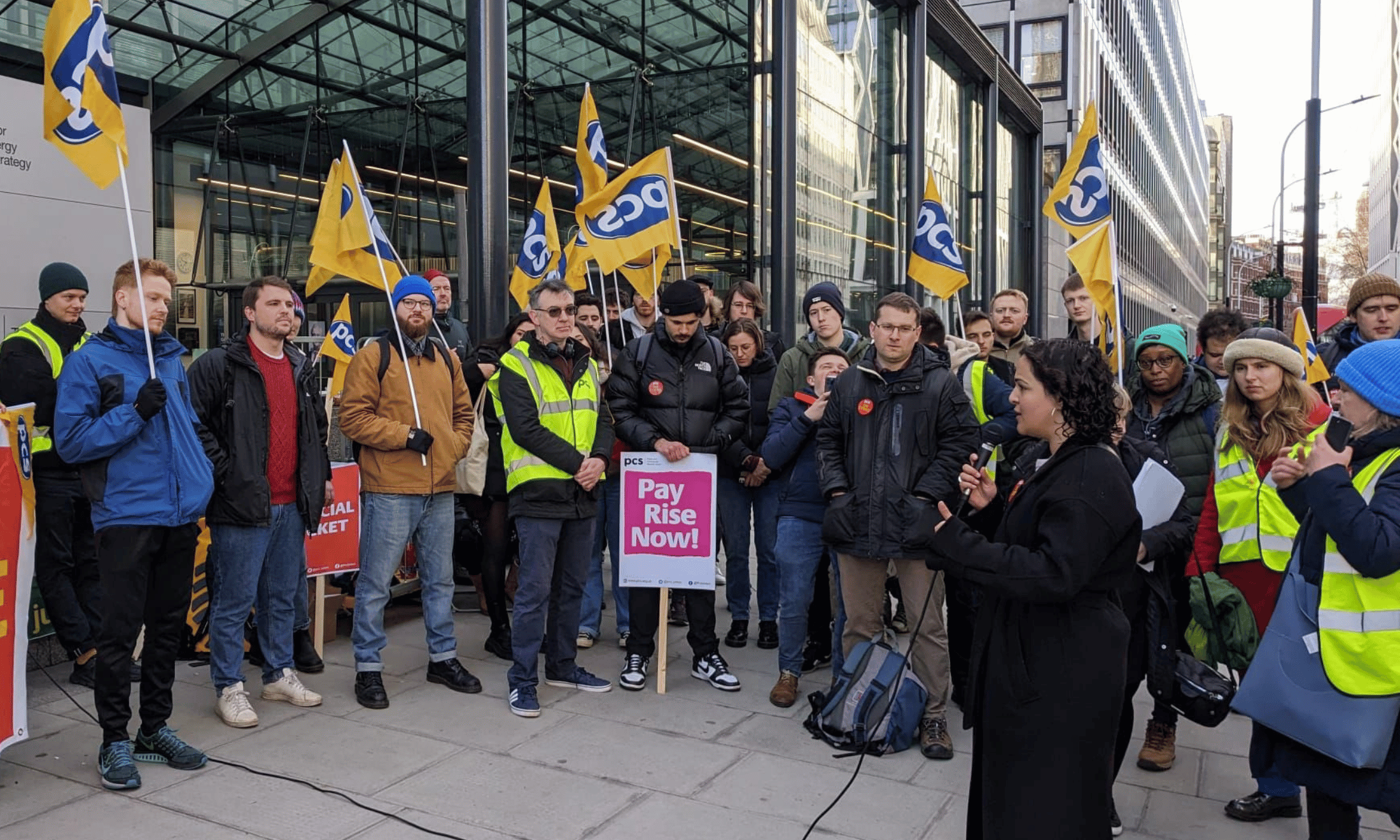

19 May 2022

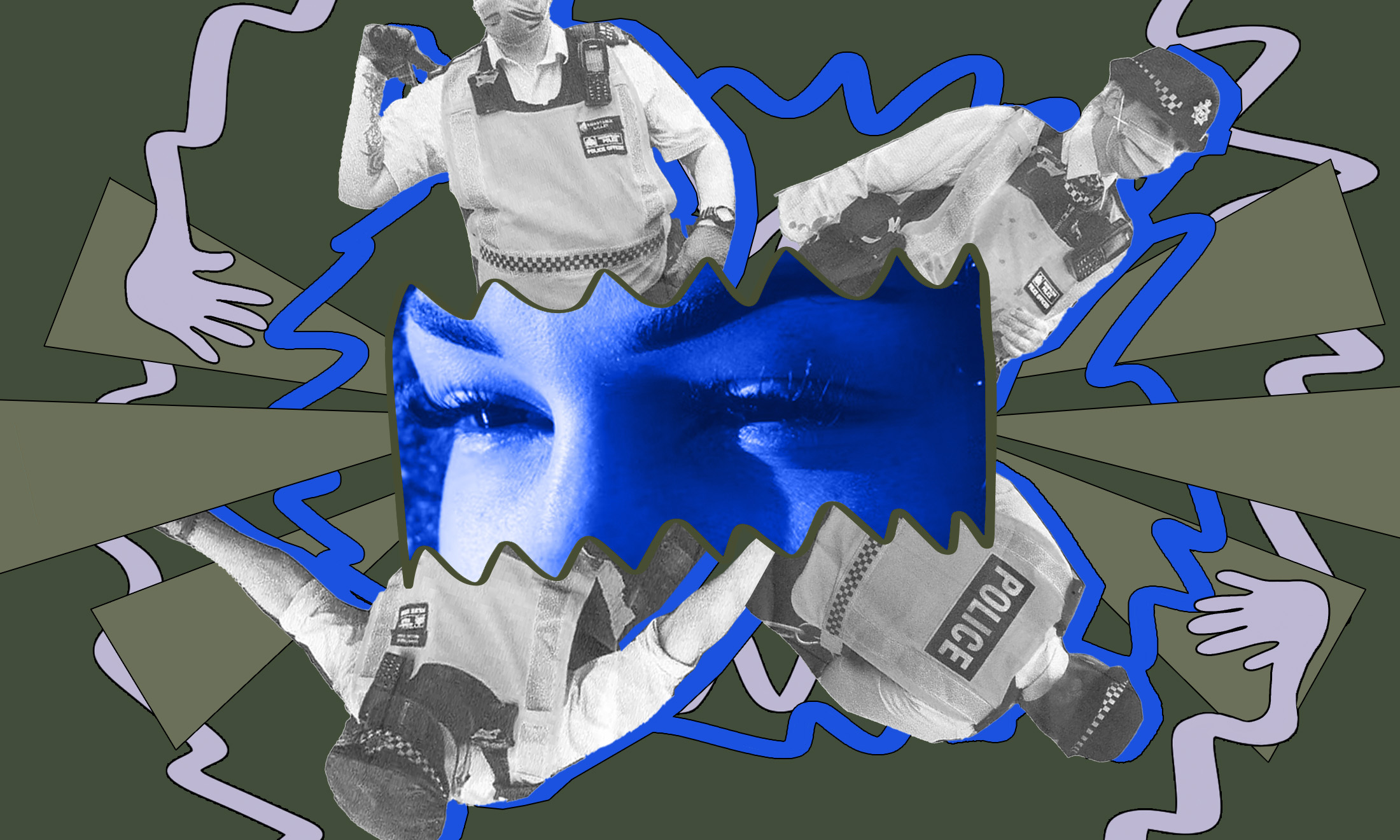

A month ago, I was on my way home from Tesco and I noticed a Black man being harassed by three armed officers. He asked me to stay and film. In the span of 10 minutes a further four armed officers arrived, circling around me and blocking my camera in an attempt to remove me from the situation. I could hear them shouting at the person I was supporting, and the officers bumping their bodies against me made me lose all semblance of calm. I swore at an officer, who threatened me with arrest if I swore again, so I looked him in the eyes, and said: “Fuck you”.

Leading up to that moment, I thought about every time I have intervened. In protests or on the streets, police officers use their bodies and their words to make me feel smaller, to craft mind games facilitating shame, hoping that will convince me to walk away. When my arresting officer was taking off my handcuffs, he said to me, “A word of advice for the future: behave yourself, stay quiet and walk away when it’s none of your business.” And this is why, despite being arrested during police intervention, I’d do it again.

“Small, sustained acts of mutual solidarity like police intervention are capable of radical change”

Intervention is a way to extend care – a way to recognise someone’s autonomy when it is actively denied. In a situation where the police are isolating and individualising a person, labelling them as the ‘danger’ within a community and signalling to the people around that this person is disposable, intervention proposes an alternative. It disputes the narrative created by the police and says there is no legitimacy in their actions. This is precisely why police officers get so defensive when people intervene – because they can see their power being threatened. It’s why I believe that small, sustained acts of mutual solidarity like police intervention are capable of radical change.

Police intervention is not just about everyday police interactions we witness on the street, such as stop and search, but it also involves intervening in the instances that lead up to the police being called. Policing relies on creating fear of strangers among us, constantly demanding us to be on the lookout. We see this in the neighbourhood watch groups that have members of the community report each other to police, landlords and the Home Office, or the numerous posters paired with the chorus of ‘see it, say it, sorted’ playing on the London Underground.

“We have become so accustomed to delegating the safety of our communities to the police, that it’s easier to deny ourselves the skills to take care of each other”

This fear of one another is not instilled in us arbitrarily, its aim is to make us believe that by policing each other we are preventing something more horrible happening. We become hyper aware of people when we see them as threats, and yet when a stranger around us is in distress, often we shift uncomfortably, look down and try to deny their presence. Part of this is because we have become so accustomed to delegating the safety of our communities to the police, that it’s easier to deny ourselves the skills to take care of each other. This narrative is further pushed by the police who pose themselves as the saviours of our communities, when in reality, it is the police who are violating us in many instances of interpersonal harm.

I have found that marginalised people, especially those who face the brunt of policing, are often the first and sometimes only people to intervene during hostile interactions with the police. I think they intervene because they see no other option. I have witnessed Black boys in my estate come together when one of them is stopped; they argue with the cops, film them, shout and resist loudly when the police try to make them compliant. They stay with each other and take their peers to trusted adults, because they know they cannot heal from this interaction away from their community.

Some adults from the neighbourhood who are concerned about building more trust between young people and the police will then come into our estate and tell us how to behave during a stop and search, implying that the reason we get arrested during intervention is due to some failure to adequately assert our rights or due to us being too aggressive. According to this narrative, if we intervene ‘correctly’, the police will apparently abide by the law under our watchful eye. They seek to legitimise the functions of policing by maintaining the idea that the person being stopped must have done something wrong. Instead of helping us resist policing, they extend the role of the police to the interveners who now become responsible for making sure the police do their jobs correctly.

“Our strength is in numbers; the more people that intervene, the safer it becomes for all of us to resist”

It’s true that when marginalised people intervene they are at greater risk of arrest or experiencing more direct violence from the police, so it is essential we focus our efforts into ensuring that they are not the only people intervening. We need to realise that our strength is in numbers; the more people that intervene, the safer it becomes for all of us to resist.

I believe intervention is a step towards finding abolitionist alternatives to policing. While it can be scary to not know these alternatives, I find comfort in a quote by bell hooks which says: “The space of our lack is also the space of possibility.” Intervention means that we as individuals and as a community are capable of responding to each other with care, that we are able to resist the narrative that we need to be protected from each other. It holds the possibility of communion and radical change.

When I was arrested, nobody stopped. On a busy Friday evening, people walked past us, sometimes slowing down or standing across the road not knowing whether to approach the situation. I like to think that they were asking themselves, “do I do something?” I wonder what would have happened if they all realised that they were thinking the same thing.

If you are unsure on where to start with police intervention, Hackney Copwatch have made a flyer that makes it simpler for you to remember how to intervene, you can also sign up to join your local copwatch group if you want to organise around policing in your local community.

Like what you’re reading? Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Our members get exclusive access to events, discounts from independent brands, newsletters from our editors, quarterly gifts, print magazines, and so much more!