Forced Covid-19 cremations in Sri Lanka are waging war on Muslim minorities

A controversial Covid-19 policy has caused Sri Lankan Muslims to fear further persecution from the state.

Mishma Nixon

01 Mar 2021

“Silence the pianos and with muffled drum/Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come,” read the opening lines of W.H.Auden’s ‘Funeral Blues’, a favourite poem of mine. It’s a heartfelt expression of grief that has been ringing in my ears for the past couple of months. Mourning is so inherent to our perception of death and grief, but oftentimes we don’t understand that it’s also a right. The right to remember the dead, the right to mourn them in a way that honours their life and their traditions.

Over the past year, communities across Sri Lanka have had far too much cause to mourn. While efforts to curtail the Covid-19 virus have been relatively successful compared to the likes of the UK, the pandemic has claimed roughly 459 lives to date. But, more than half of them are Muslim, say community leaders – despite Muslims only accounting for 10% of the country’s population.

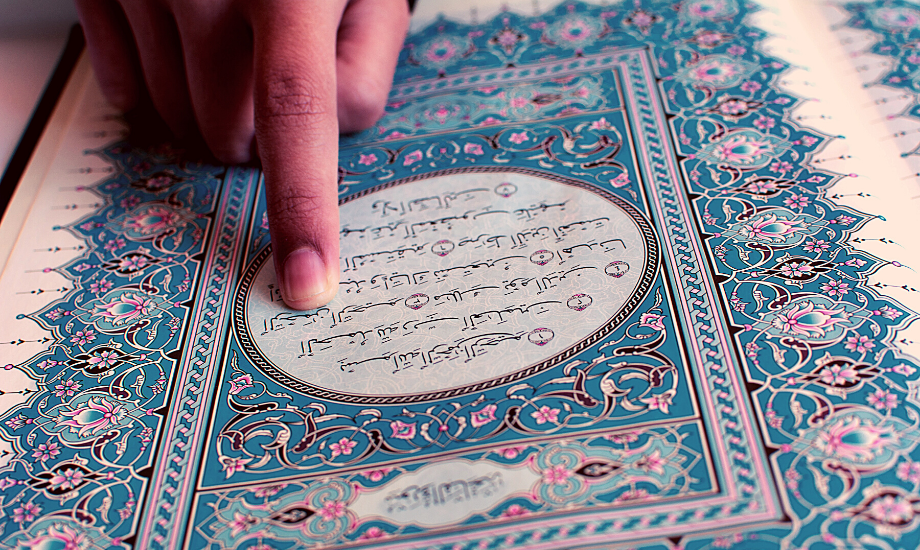

The disproportionate death rate is not the only tragedy to hit the community; even in death, Muslim victims of Covid-19 are being desecrated. Pandemic policy in Sri Lanka insists that the bodies of people who have died of Covid-19 must be cremated. But Islamic tradition strictly forbids cremation; the dead are honoured through burial, with their heads facing towards Mecca. For grieving families, the government edict has led to outcry and there are suspicions that the policy is simply the latest effort to discriminate against the Muslim population in Buddhist-majority Sri Lanka.

“Pandemic policy in Sri Lanka insists that the bodies of people who have died of Covid-19 must be cremated. But Islamic tradition strictly forbids cremation”

While cremation is standard practice in Buddhism, Muslim and Christian minorities in Sri Lanka bury their dead. The policy has been bitterly controversial since it was announced in April 2020, despite the World Health Organization’s assurance that “both burials and cremations are permitted”, for laying Covid-19 victims to rest. Experts in the country supported both options remaining available to grieving families, with UN officials calling forced cremations a “human rights violation”. Nevertheless, the cremations in Sri Lanka went ahead, with at least 200 Muslims alleged to have been cremated during the pandemic.

Outrage reached a peak in December when a 20-day old baby, named Shakyh, was forcibly cremated, against the express wishes of his family, and concern about a potential misdiagnosis as to the cause of the infant’s death. People gathered outside the cemetery in which Shaykh was cremated, and carried out silent and peaceful protests demanding justice. To show solidarity with the family and the rest of the community, non-Muslims and Muslims poured out to tie white handkerchiefs onto the gates of the cemetery. The protests didn’t initially deter the government – in fact protestors were threatened to leave and the handkerchiefs were ripped off and discarded by police. International media attention after Shakyh’s cremation, and involvement of the UN, eventually resulted in prime minister Mahinda Rajapaksa making a statement on 10 February that seemingly allowed Covid-19 burials to return.

Yet, the authorities backtracked in the immediate aftermath, as speculation and confusion about this ambiguous statement were exacerbated by claims that Muslims were still continuing to be forcibly cremated and members of the ruling party issuing denials regarding the prime minister’s statement. Finally, on 26 February, the government issued an official statement that Covid-19 burials will now be allowed, which coincided with Pakistan prime minister Imran Khan’s visit to Sri Lanka – and more protests from Muslim groups in Colombo, the capital city.

For Muslims, this is all part of a familiar pattern. The Muslim community in this country has been facing targeted harassment and discrimination for years now, with the 2018 anti-Muslim riots, and the blatant Islamophobia after the Easter bombings in 2019 culminating with the election of Gotabaya Rajapaksa (brother of the prime minister) as president later that year. Rajapaska based his campaign on national security and the promise to combat “Muslim extremism”, and won the elections with a 52.5% vote, despite gaining almost no support from minority groups.

The rhetoric of cremations around Covid-19 has enabled the government to position anti-Muslim sentiments as a public health concern, similar to how the aftermath of the Easter attacks led way to Islamophobia in the guise of security concerns. Back in 2019, Muslim shops lost customers and face coverings were banned in public. Now the apparent fear of the virus has helped normalize the outright dismissal of the traditions, dignity, and grief of vulnerable Muslim populations.

The hatred towards Muslims in this country is a growing parasite being fed by the government’s encouragement. Recently, one of my neighbours casually told me that “there’s no space left to bury people”, and I sat at the dinner table with my uncle who proclaimed that Muslim communities were “making a big deal [out of] such a simple thing”. People also continue to point towards the Easter bombings in justification for anti-Muslim policies, as if the actions of one extremist group means it’s acceptable to remove the rights of an entire community.

“The rhetoric of cremations around Covid-19 has enabled the government to position anti-Muslim sentiments as a public health concern”

The policy might finally be consigned to the scrapheap, but this is not the end of discrimination for Muslims in Sri Lanka. The hate and bigotry is here to stay, mirroring rising Islamophobia in neighbouring countries. But it has been met by rising resistance as well. Sri Lankan minorities are joining hands in the fight against persecution.

In early February, thousands of people from Tamil and Muslim communities in the north took part in a five-day march. The march marked a new allegiance between the communities, after years of strained relations during and in the aftermath of the civil war. While the rally was originally organised to raise attention to unheard demands of the Tamil community, the inclusion of the Muslim community saw a linking of grievances and solidarity which poses a very real challenge to the discrimination sanctioned by the state. If the government doesn’t correct course, the pandemic might well prove to be the breaking point for those who have been underfoot for so long.