‘I’ve never needed to read de Beauvoir’: Françoise Vergès on reclaiming feminism for racialised women

The French political scientist explains why 'decolonial feminism' is her great hope for the future.

Hanna Bechiche

21 May 2021

Victoria Smith

Growing up in France, the word ‘feminist’ was glued to memories of women glaring at my hijabi mother and friends and trying to lecture them. It brought up the image of three women stripping naked on the stage of a Muslim conference in the name of ‘liberation’ – with no mind for any Muslim women who told them their actions were offensive, not freeing. For a long time, I felt guilty for disliking the word feminism.

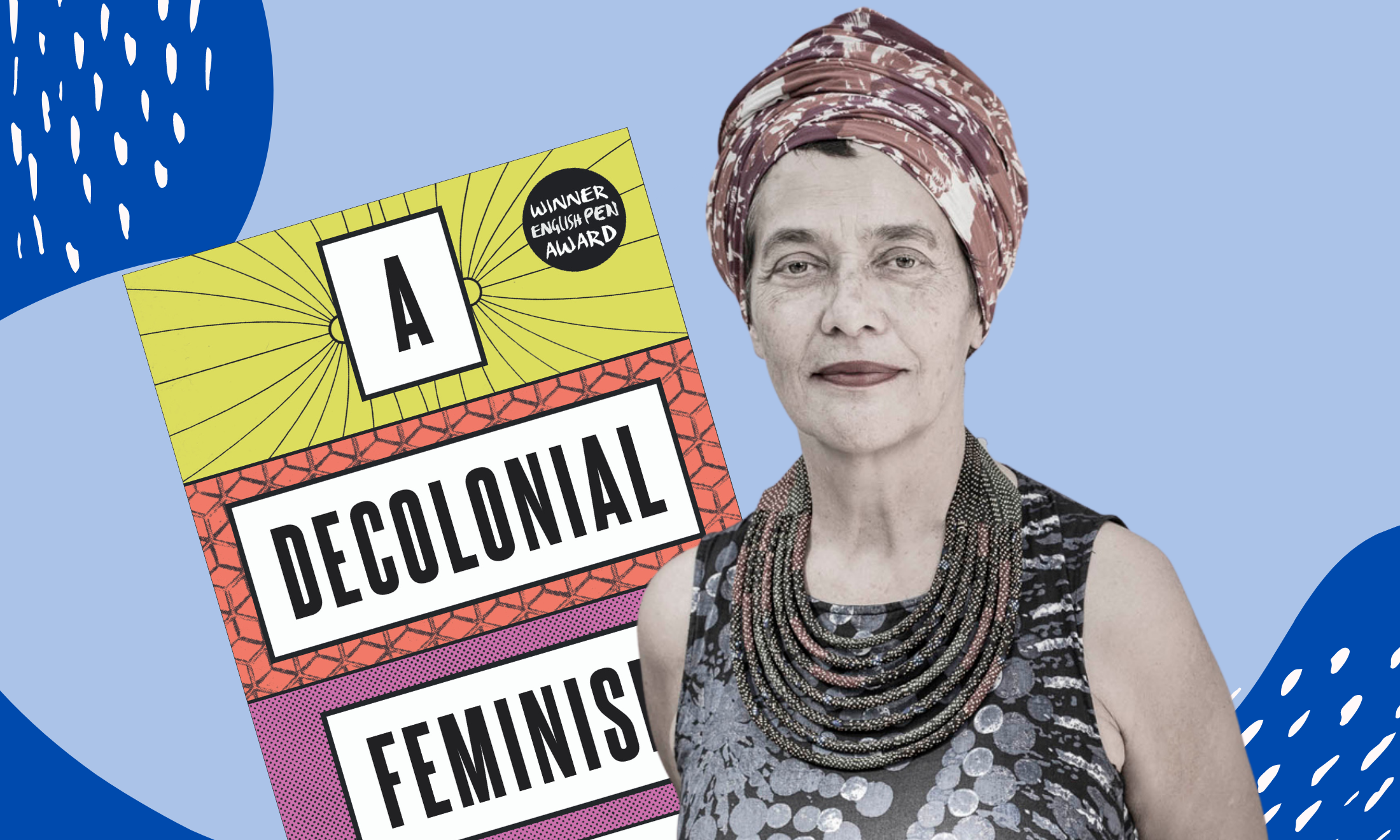

The guilt washed away once I read Françoise Vergès’ new book, A Decolonial Feminism. Originally published in 2020, but now translated into English, the political scientist’s latest work powerfully outlines the reasons why mainstream feminism has been failing and excluding women of colour since its conception. Its main goal is to define another form of feminism, a ‘decolonial’ one that studies all forms of oppression and is rooted in dismantling racism and imperialism. “The term ‘feminist’ is not always easy to claim,” Françoise writes, a few pages in.

“The betrayals of Western feminism are its own deterrent, as are its heartless desire to integrate into the capitalist world and take its place in the world of predatory men and its obsession with the sexuality of racialized men and the victimization of racialized women.”

In the heart of a historically insurgent neighbourhood of Paris, I head to meet her. Françoise’s apartment is a quiet place, where books line the walls from ceiling to floor.

“The idea is not to rip the word feminism away from mainstream, white feminists,” she states as soon as we start the interview. We’re in her living room; outside birds are chirping, and Françoise is nonchalantly eating almonds.

“The idea is to define a feminism I can associate myself with, one racialised women who’ve been leading anti-colonial and anti-racist fights can associate themselves with.”

As Ashley J. Bohrer explains in the introduction of the book, the word ‘white’ is not used solely because these feminists are white, but because white feminism “reaffirms a white vision of the world, a white horizon of analysis. [It] partakes in and reproduces the assumed civilizational superiority of the North.” White feminists are called so because they sustain colonialism and systems of white supremacy instead of uprooting them.

With a flick of the hand, Françoise pushes aside many of the accusations such feminists have thrown at her since the release of her book. “I never talk to these women. I don’t want to explain myself to them. I write for the ones who share the same decolonial fights as I.”

Growing up in La Réunion and Algeria, raised by communist and politically active parents, Françoise was baptised in anti-colonial environments. “I’ve never needed to read Simone de Beauvoir to learn what it was to be a feminist,” she explains. “It was everywhere around me growing up.”

“Civilisational feminists preach a universal feminism, the false idea that there is a universal and equal experience of being a woman. There is not”

Françoise nods vigorously when I speak of my own experience with mainstream feminism, and rolls her eyes when I mention the naked women crashing the conference on women and Islam. “In France especially, feminism is too intertwined with the white bourgeoisie,” she tells me. In her book, she names these white bourgeois feminists “civilisational feminists”. When I ask her what prompted her to choose this term, she points out the perverse similarity between the discourse favoured by white bourgeois feminists and the colonial Empire’s discourse.

“Civilisational feminists have inherited a lot from colonialism,” Françoise asserts firmly.

“They’ve borrowed the vocabulary of the civilising mission word for word. ‘We need to save these people from oppression, to show them the way to liberation.’ They’ve turned women’s rights into trump cards of neo-colonialism. Their discourse stinks of white saviourism.”

Quickly, she spells out their reasoning. “To them, male domination is the worst kind of oppression. This is why they feel entitled to speak on behalf of women of colour. They believe the patriarchy to be worse than racism, capitalism, and imperialism. Obviously, they don’t take into account the fact that colonialism cemented the patriarchy.”

When I ask if decolonial feminism is synonymous with intersectional feminism, Françoise shakes her head. “Intersectionality is not enough. It only studies class, gender, and race.

“I’d rather call it multidimensional feminism, because it takes into account every single thread of society: cultural, international, geopolitical, historical, etc. For example, when discussing women in Pakistan, intersectionality is inadequate. We must take into account the ramifications of imperialism, of tradition, of international policies as well as class, gender, and race. You have to pull on all of the threads, and ask yourself, did I study everything? Have I taken into account everything that makes up the experience of Pakistani women?”

She thinks for a minute, before adding: “Civilisational feminists preach a universal feminism, the false idea that there is a universal and equal experience of being a woman. There is not.”

Naturally, we find ourselves talking about the experience of Muslim women in France, and the recent vote to ban hijabs. A large section of A Decolonial Feminism is dedicated to underlining the role French civilisational feminists have played in the rise of Islamophobia.

“Intersectionality is not enough. I’d rather call it multidimensional feminism”

“French feminism is tinted with orientalism,” Françoise observes. “European colonisers were obsessed with unveiling North African women, and similarly, civilizational feminists confuse women’s liberation with unveiling. They’ve turned Islam into their new enemy, the main pillar of the patriarchy.” She laces her words with contemptuous emphasis, to stress the ignorance of such logic.

“In the 1990s, French feminists centered their entire agenda around the question of the veil. They’ve used it to propel themselves into French politics. They’ve been invited to every public debate on the veil since, and they’ve no desire to hand the mic to French Muslim women. They believe them to be accomplices to the men who wish to take away the rights French women have courageously won. They’ve successfully pinned Islam and Muslim men as the number one enemy of the French nation.”

After two hours of enlightening conversation, I ask a final question. “How can one be a decolonial feminist?” Françoise’s reply is assured and full of hope for the future of decolonial politics, which fills me with renewed energy.

“The first step is to stop explaining or justifying yourself to white [civilisational] feminists,” she says. “Put them aside, don’t give them importance. Focus your energy on the ones who fight the same fights as you, on the communities who’ve put up resistance.

“The second step is to reclaim the forgotten and [hidden] history of racialised women’s fights. Women of colour are fighting not only for equal rights but also against exploitation, injustice, and oppression.

“Women in the Global South have always been in the front lines of feminist fights, yet their voices are never heard unless they’re instrumentalised. You have to uphold their voices, to read their material, to recenter their narratives. Lastly, the most important thing is to ask questions. You need to stay curious, always.”

She leans closer, raises a finger and repeats herself. “You need to stay curious”.

The English translation of A Decolonial Feminism by Françoise Vergès is available now from Pluto Press.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?